In January 1995, Tatyana Ilyuchik received a letter from her son. It said he had been sent to fight in Chechnya. After reading it, she thought of the anti-war march by the Committee of Soldiers’ Mother she had seen on TV and decided to go to the Chechen Republic. She ended up staying there for six years.

Along with other women, whose sons had been sent to fight, Tatyana Ilyuchik tirelessly looked for her son, hoping that he was being held captive. She slept in a railroad car on a spare railway track, baked bread for Salman Raduyev’s [a leading Chechen guerrilla fighter], fighters and learned to identify bodied by a dental crown. While she was in Chechnya, her husband died back in Perm. “It was all lies,” she says, thinking back to the time when she campaigned against the war. Twenty years later, Tatyana Ilyuchik believes that the Chechen wars were not fought in vain and supports the “special military operation”. In a letter to soldiers, fighting in Ukraine, she wrote: “I am proud of your devotion to the Great Russia. Keep it up, great sons of Russia”

The original piece was published in June 2023.

“Vovik, you have to hold on”

Tatyana keeps a half-smoked cigarette in a glass medicine flask. Last year her son’s friend Andrei brought her the cigarette and told her that they had planned to finish it together when Vladimir returned home. Tatyana’s son died in Chechnya many years ago, but Andrei had kept the cigarette for 28 years. He died in April 2023.

“What kind of a boy was he? The best, the best boy one could wish for, Tatyana Georgievna says about her son Vladimir and starts coughing. Here we go… I’m getting nervous already… he was nimble, inquisitive and very hard-working. He used to do all the hard work in the countryside with me and help his father”.

Until the early 1980s, the Ilyuchik family lived in the centre of Perm, a city near the Ural mountains, in an old merchant’s house divided into communal cells with thin plywood walls. Seventeen tenants shared one kitchen and one toilet. By 1982, this block between Komsomolsky Avenue and Kuibyshev Street had been demolished, a big hotel complex had been built in its place, and the Ilyuchik family had relocated to the other side of the river. Vladimir’s parents still took their son to the city centre until he finished school, an hour each way in a packed bus.

“We’d place him between us, but he would get very sleepy and every now and then his legs would just bend and he’d fall asleep. I would shake him and say: “Vovik, you have to hold on,” Tatyana recalls.

They were poor, but they managed to put some money aside to travel to other cities. In Volgograd, they bought Vovik two car toys: a black Volga and a red racing car with “Rainbow” written on the rear wing. They now sit on a shelf in front of the young man’s headshot.

After graduating from middle school, Vladimir went to the Slavyanov Polytechnic College to become a machine tool operator.

“He was a techie, his mother recalls. He used to play with these machines, disassembling and reassembling everything, buzzing”.

Tatyana remembers a funny story. Her son and his friend needed to do some work on an old washing machine for their thesis. When they started the turbine, it took off and almost hit the chandelier, she recalls.

The young men submitted their thesis in the winter of 1994, and in the spring Vladimir was drafted into the army, despite his poor eyesight. By the time he was in sixth grade, his eyesight had already fallen to -4 (the doctor said it was due to a growth spurt), and by the time war in Chechnya was launched, his eyesight was already at -6.

Vladimir joined the motorised riflemen in a military unit stationed in the village of Markovsky in the south of the Perm region. His mother went to visit him. They didn’t learn anything, but they just built houses for officers, she recalls.

“Why was that necessary?”

Tatiana learnt about her son being sent to Chechnya from a letter that arrived shortly after Christmas 1995. Tatyana found it torn up by the mailboxes.

“Someone took it out of the mailbox and tore it up. Why was that necessary? Tatyana shrugs. Well, there are a lot of idiots out there. They took it out, but apparently, it wasn’t that interesting, so they tore it up”.

Vladimir wrote that they were first sent to Samara, and then straight to the Ossetian town of Mozdok. This was where in 1994, one of the groups of federal forces was deployed to advance into Chechnya, and an operational headquarters to take over Grozny was set up, headed by Defence Minister Pavel Grachev.

In Mozdok, an officer told the soldiers to quickly write letters and offered to drop them in a regular mailbox, bypassing the “Moskva-400” field mail. All letters to and from Chechnya were being sent using the Ministry of Defence’s field post service via the capital. Soldiers’ relatives wrote the postcode 103400, Moscow-400, the number of the unit and the soldier’s surname. These letters took a long time to arrive, between three to four months.

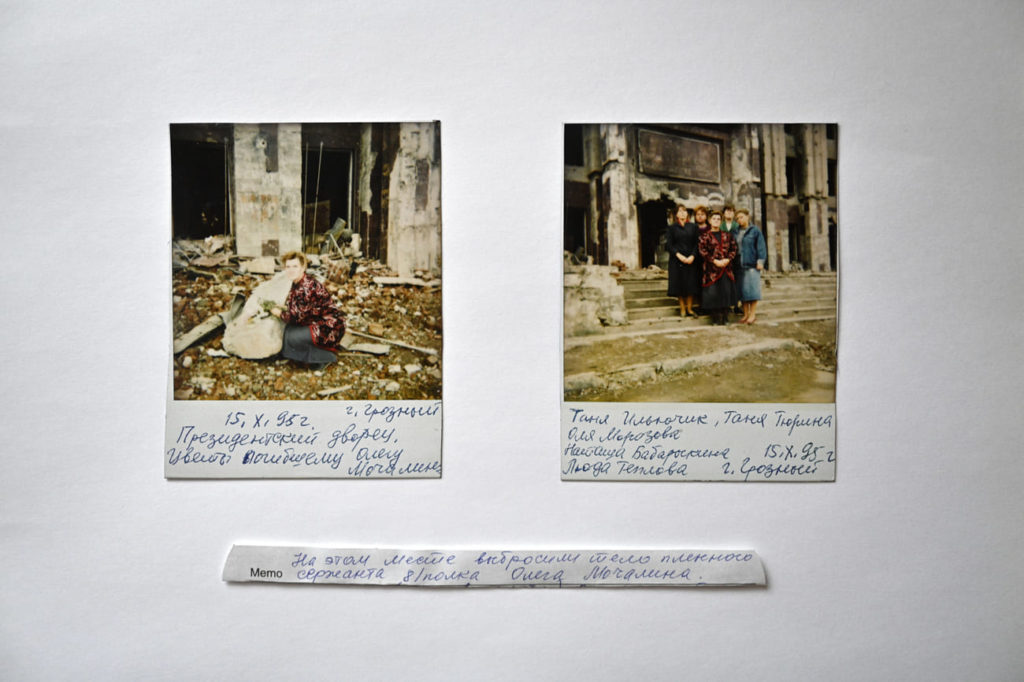

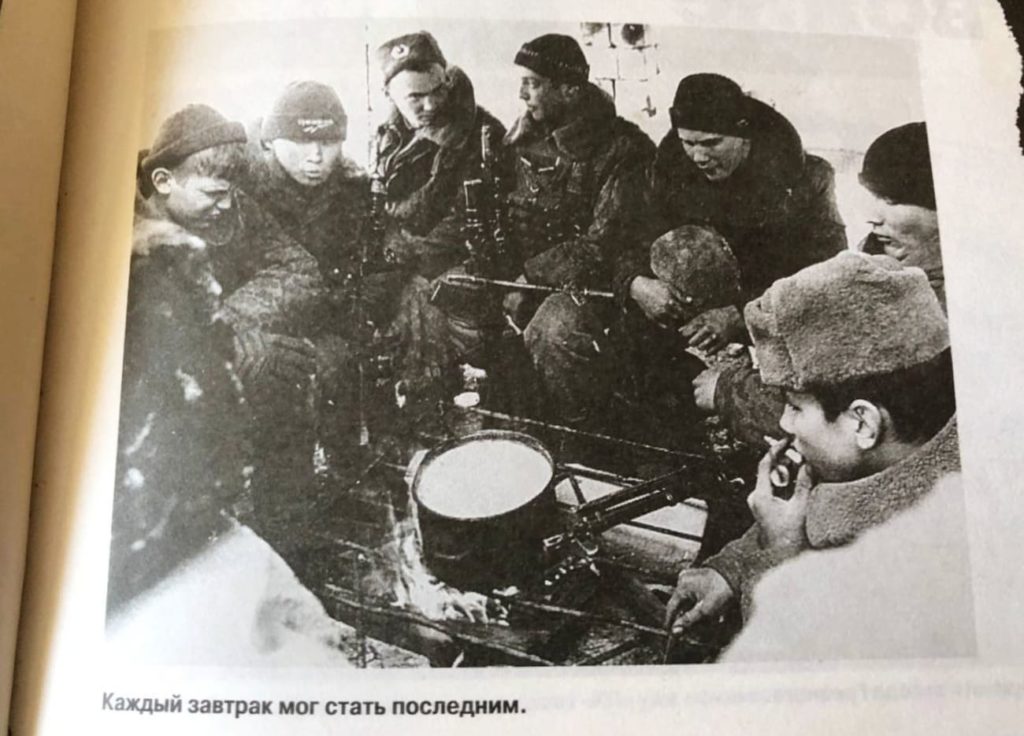

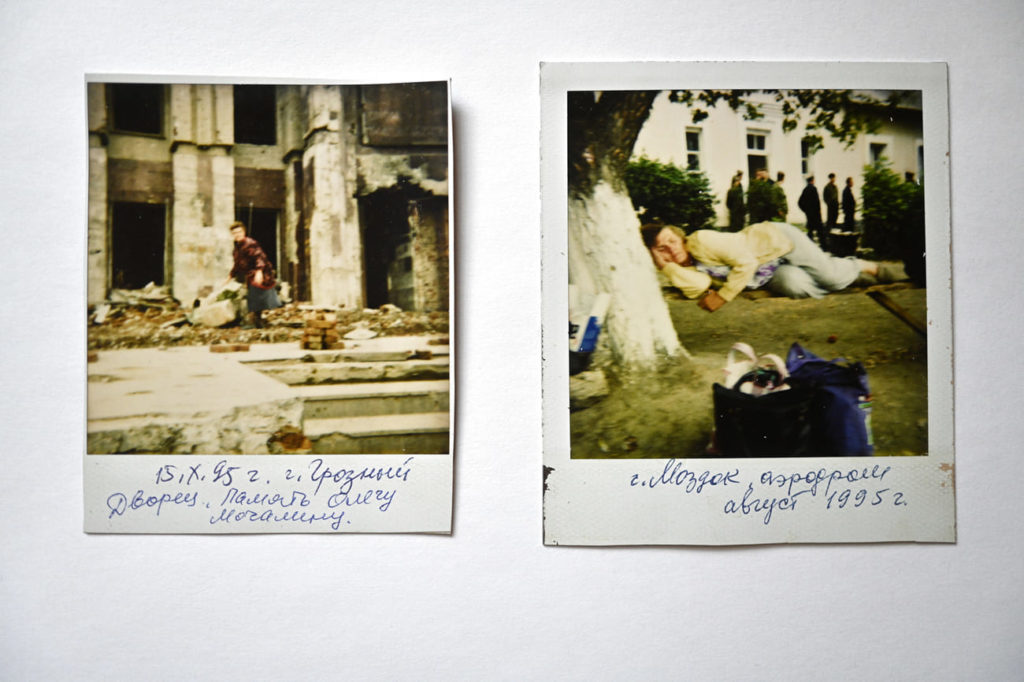

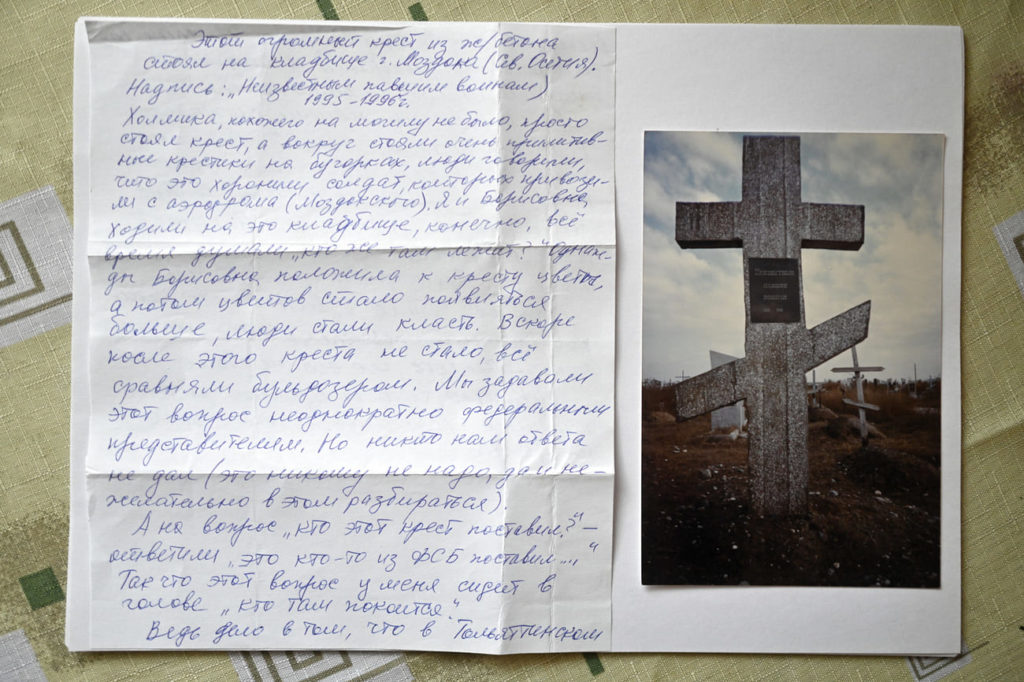

“Let me find it… — Tatyana says, leafing through the “Book of Memory. Chechnya”, a chronicle of the war based on articles by war correspondents of “Komsomolskaya Pravda” from December 1994 to October 1996. Finally, she shows a photograph, captioned “Every breakfast can become last”. The picture shows soldiers sitting around a fire, with a blackened pot of porridge on the fire grate. The third from the right is Tatyana’s son Vladimir. What if it was taken the day they wrote letters to their parents, she wonders.

Vladimir fought in the battle near Grozny railway station on New Year’s Eve as part of the 81st motorised rifle regiment from Samara. The soldiers got surrounded and executed by militants. By the time Tatyana received that letter from her son, he was already dead.

“It was all lies.”

When Tatyana found out her son had been sent to Chechnya, she went to the Perm regional military enlistment office. But to no avail.

The Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia organised the first anti-war march in Moscow and a Memorial service for all those who died in Chechnya in January 1995. Tatyana saw that march on TV and decided to start looking for her son.

“Why am I sitting at home? she recalls thinking. This way, I won’t find out anything anyway… They lie, it’s all lies”.

Vladimir wasn’t the first man in Tatyana’s family that had gone missing during the war. A month after the beginning of the Great Patriotic War [in Russia, June 22, 1941, is considered the start of the Great Patriotic War] her father Georgy Shavshukov went to the front. He died in November 1942, having found out from his wife’s letters that he had become a father to a daughter named Tatyana. The military enlistment office reported that Georgy died near Tver, but his body was never found.

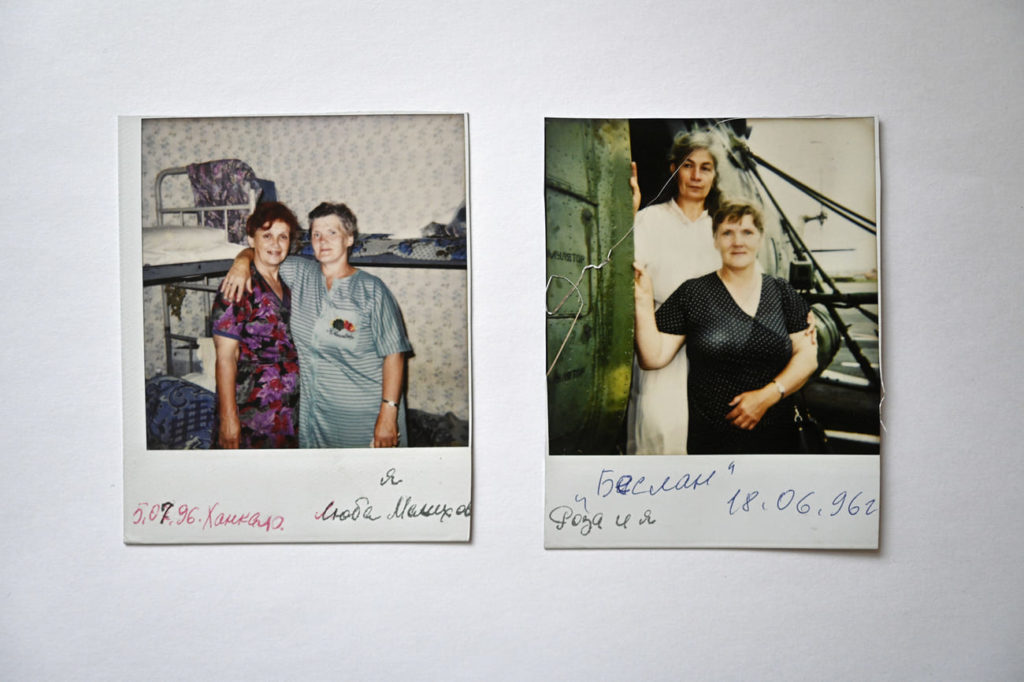

In April 1995 Tatyana came to Mozdok. Mothers of missing soldiers were sleeping in a gym of a technical college, but there was no space for Tatyana there. She made a bed in a railcar on a spare track near the railway station. Third-class carriages had been converted into an overnight shelter for railway workers, and those who missed their trains also slept there. Her ‘roommates’ were often elderly people who travelled from Grozny to Stavropol to collect their pensions, Tatyana recalls.

She slept in that carriage for more than a year. For breakfast, she made broth from a quarter of a chicken cube. When she settled in, she started buying lard at the market in Mozdok, and for lunch, she’d allow herself a luxury: a big bowl of soup from the canteen. She lived off savings she had brought with her.

All year long, soldiers’ mothers would go to the airfield where the headquarters of the Joint Group of Federal Forces was located. Officers would give them the names of the soldiers in captivity and of those on the list of the dead.

“Of course, we had meetings, Tatyana says. We would get together and cry. But we couldn’t just cry, we had to do something. Why listen to lies? It was too much”.

Tatyana was hoping her son was still alive. The officers reassured the mothers, telling stories of soldiers changing into civilian clothes after battles, wandering around Chechnya and being captured.

“As long as someone visits the grave”

In 1996, the soldiers’ mothers moved to Grozny, and so did Tatyana. She remembers the shocking first impression, as she got to the city market.

“There was no sky, everything was black [because of burning oil wells], and the curfew was about to start, she says. I looked around: there were no Russians, and all I could hear was the locals speaking “gyr-gyr-gyr-gyr-gyr-gyr”.

She remembers wearing a white tracksuit and everyone staring at her.

Tatiana spent her first night in Grozny with a woman she had met on the train in Mozdok, in a barrack in the middle of Grozny’s ruins. In the morning, the Chechen woman told her how to get to the Severny airport, where the feds were stationed. The other soldiers’ mothers were already there, housed in a 16-square-meter room in the airport hotel.

The mothers, however, were hardly ever there. They were going around Chechen villages with copies of their sons’ photographs, trying to find out if they were being held captive. Sometimes the feds took them along to exchanges: the fighters were more willing to hand over conscripts if the parents were present.

One such exchange in a village outside Kurchaloy didn’t go to plan. According to Tatyana, the mothers were sitting on top of crates of weapons in a small old railcar with a fire stove, waiting for a soldier to arrive. A Chechen came in and asked: “Is anyone here from Perm?” Tatyana jumped up, but the guy they had brought wasn’t Vladimir.

“And our representative office, those bastards, didn’t take him, Tatyana says. No, we don’t want him, he’s a deserter, we want someone who fought in the war”.

Tatyana asked the prisoner for his home address and told her husband to inform his parents that the militants were ready to hand him over, but nobody from his family came for him. Tatyana’s husband Mikhail stayed in Perm.

“He was very worried, he cried his eyes out, says Tatyana. He didn’t want to let me go, but I told him: “I’m not asking you, my son is there”.

In 1996, Tatyana received a certificate stating that she was searching for “a son in Chechnya who is being held captive by illegal armed formations”. The document effectively ordered the commanders of the units to assist the mother with transport and food. With this certificate, Tatyana could move around military units, hospitals and participate in the exhumation of bodies.

“In Khankala, near the hospital, there was this large area, Tatyana recalls. They would pile up the bodies on this square, and a helicopter would take them to Rostov. So this huge heap… That’s why I can’t look at foil — this heap was covered with foil”.

Together with the bodies of soldiers, mothers flew to the 124th forensic medical laboratory of the North Caucasus Military District. Tatyana remembers asking the expert Kostya to “thoroughly search” for her son, but he kept saying that he had not seen anyone who looked like Vladimir.

Now she is convinced that her son’s body was given to other parents, taken away in a zinc coffin, which was never to be opened.

“If they gave him away, God bless, Tatyana sighs. As long as he stays there, where someone took him in, as long as someone visits the grave”.

“They fought at night, like wolves”

In August 1996, Russian General Alexander Lebed and Aslan Maskhadov, chief of staff of the armed forces of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, signed a truce agreement in Khasavyurt. Mothers continued their search for their sons, travelling to excavations of mass graves. In one of the villages outside Urus-Martan, Tatyana recalls, a Chechen had marked the grave site with sticks so that the bodies could be found later. Mothers used these sticks to open the jaws of the dead, hoping to recognise their sons by their teeth.

For the whole of 1997, the soldiers’ mothers lived in Grozny in a private house on Volnaya Street with the militants of Salman Raduyev, a field commander who was sentenced to life imprisonment for terrorism in 2001 but died a year later in the White Swan prison in Perm.

Mothers were not hostages, they could leave any day, but the militants, according to Tatyana, used them for cover. They bought flour for the women, and Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov sent them money.

“They fought at night, like wolves. [Raduyev claimed responsibility for the terrorist attacks on railway stations in Pyatigorsk and Armavir in 1997], They came home covered in blood. They would go out… just like the saboteurs today. A truce is a truce, but war is war. But we fed them. I made bread for them. We didn’t have a choice”, Tatyana says.

Vasily Sidorov, the father of a soldier from Satka, lived in a barrack attached to the house on Volnaya Street. He knew that his son had been buried somewhere, but couldn’t find his grave. One day militants brought him his son’s excavated remains in a chequered bag, like those used by shuttle traders in the 90s.

In 1998, Georgy Kurin, the Russian government envoy to Chechnya, rented a house for the mothers next to the OSCE mission on Mayakovsky Street, near “The Three Fools Monument” (the nickname of the monument to a Russian, a Chechen and an Ingush). Tatyana stayed in Chechnya, still hoping that her son was alive. She only left once: when her husband died back in Perm.

“He was still wheezing”

It was only in 2000 that Tatyana returned home from Chechnya. After six years of unsuccessful searches, she learnt about the circumstances of her son’s death from Sergei Kiselev, who was travelling with Vladimir in the same IFV (Infantry fighting vehicle). She got his details from the regiment headquarters.

A colleague of her son’s told her that on New Year’s Eve, their car was ambushed on a narrow street near the railway station. It was foggy and nobody was protecting them from the air.

“It was a meat grinder, Tatyana relays the story of her son’s fellow soldier. And these guys, who jumped from the IFV, ran into some yard, there was a stack of wood… Vovka was shot in the back. As Sergei was dragging him in, he was still wheezing”.

In a letter to the military commissariat of the Republic of Karelia Lieutenant Sergei Sidelnik confirmed the death of Private Ilyuchik in the battle, which took place in a private house after his IFV was hit. The other soldiers were wounded, taken prisoner and taken to the basement of the presidential palace. In 2001, Vladimir Ilyuchik was officially pronounced dead by the Kirovsky District Court of Perm.

Despite the death of her son, Tatyana refuses to believe the Chechen campaigns were in vain.

“Back in my days, we opposed the war in every way we could, Tatyana says. Only later did we realise that if our guys had not shed their blood for our country’s territorial integrity, there is no telling how far this ISIS** group would have come”.

Still, Tatyana admits that although the military operation in Chechnya was necessary, they could have spared the conscripts: “They could have sent others to fight, not the snotty soldiers like our guys”.

“Keep strong, great sons of Russia”

Tatyana also supports Russia’s new — special — military operation.

“If we hadn’t launched the special operation, would we still be living on our land or not? Tatyana argues. Putin didn’t start the war, he is trying to end it. I ate “Bush legs” [a nickname for chicken leg quarters imported from the United States in the 1990s post-soviet countries], and I don’t want to eat “Biden legs”. I don’t want to fall under America’s wing. It’s scary, painful, we roar, we pray, but… our guys will win anyway”.

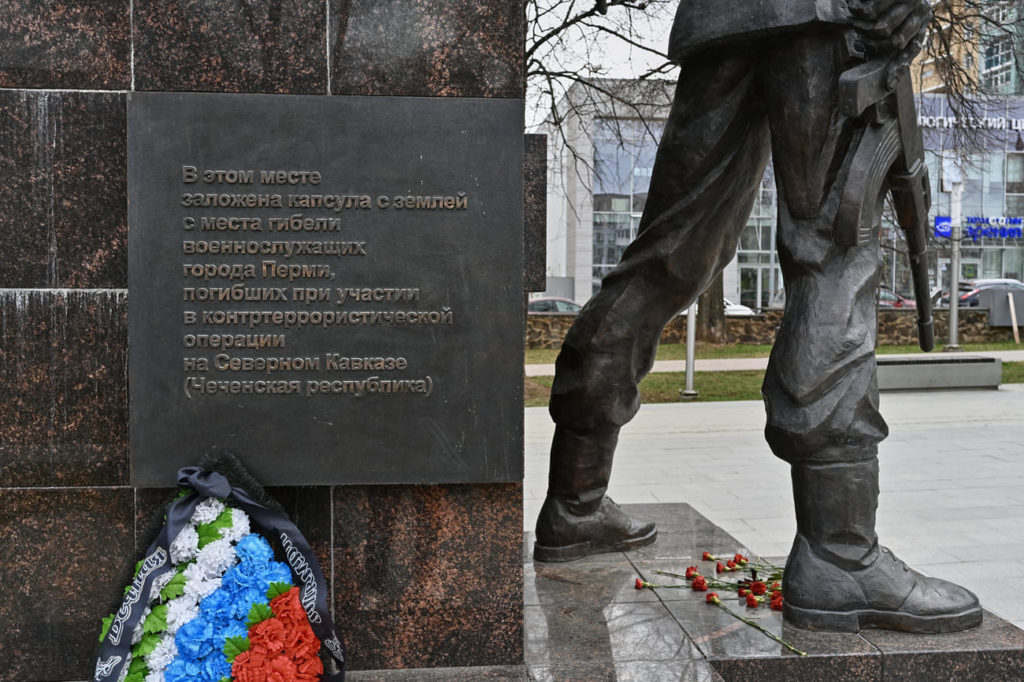

By 23 February 2023, Tatyana, along with other mothers from the Perm regional branch of the national public organisation of families of fallen defenders of the Fatherland, wrote a letter to the front. “There are no soldiers like ours, she wrote in the letter. I bow before your courage, fortitude, decency. I am proud of your devotion to Great Russia. Stay strong, great sons of Russia”.

Tatyana doubts that there are many missing Russian soldiers in Ukraine now.

“Now it’s all out there, if one dies, it’s known, or if one’s taken prisoner. I don’t think there are any missing, says Tatyana, who spent six years trying to find the truth about her son. Perhaps, there are a lot of unidentified ones, because they are all disfigured”.

**The Islamic State (ISIS) is considered a terrorist organisation in Russia.