The State Duma is considering a bill restricting access to books written by ‘foreign agents’ in libraries. Although members of the parliament went on holiday in August before passing the amendments, some libraries decided to act preemptively. The New Tab reporters talked to librarians from different regions of Russia to find out what they think about officials interfering in their work, why some librarians, despite their pro-government views, condemn censorship, and why some readers go as far as stealing books written by ‘foreign agents.’

The original piece was published in August 2024.

“Write off the books into our caring hands”

“If I borrow a book and do not return it, i.e. steal it, what should I do, what do the rules say?” Librarian Natalia** from a small town in the Moscow suburbs has been getting questions like this more and more often. She thinks this is how readers try to save books or get them for their personal collection while they still have the chance.

“People ask us: ‘do you have anything else to write off? Then write them off into our caring hands”, Natalia says.

Some libraries have already started to get rid of books written by ‘foreign agents’, even though the law doesn’t require it yet. The works of Dmitry Glukhovsky, Mikhail Zygar, Dmitry Bykov and other writers included in the Ministry of Justice register are being written off alongside old books and thrown out for recycling. As Natalia puts it, the libraries ‘fell before the shot was fired”.

She had heard from colleagues that some had already received an official letter recommending they remove the books of ‘foreign agents’ from the reading rooms, ‘to avoid irritating the public’. A list was attached, but she had not seen it herself.

“It’s not at the ‘451 degrees Fahrenheit’ point yet, the books are not being burned, but just written off and recycled for paper. Some attentive citizens walk around, looking, saying: “Akunin’s been removed, well done,” says Natalia about those readers who have no intention of ‘saving’ literature.

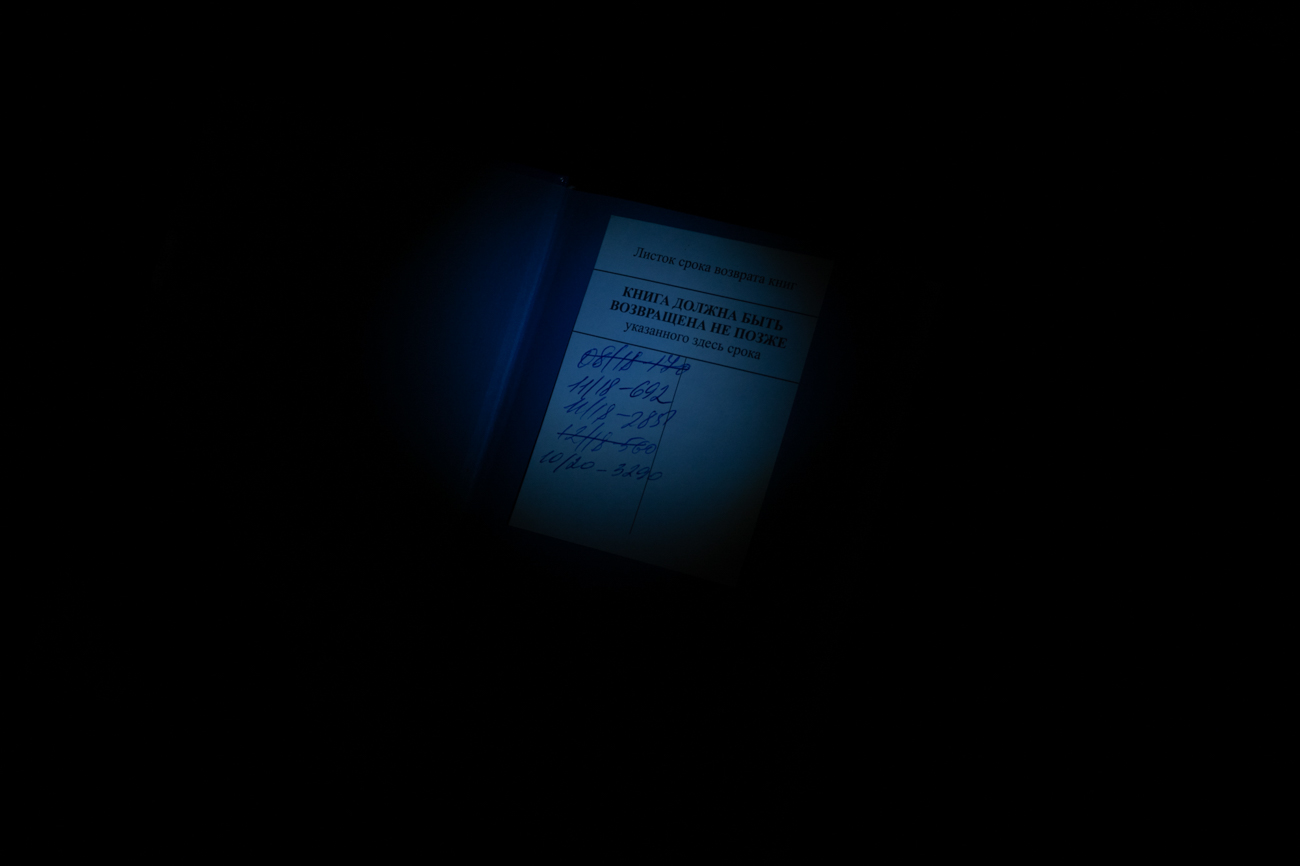

In the library where she works, the books of ‘foreign agents’ were not thrown away, but hidden in a “closed” collection.

At first, Natalia wanted to label covers with a note ‘This message (material) was created by a foreign agent…’, but her colleagues talked her out of it, saying ‘it’s a disgrace for librarians’. For the time being, they decided to just slap on the stickers with an age limit of 18+, as required by law.

Sometimes books by ‘foreign agents’ that readers bring back after a loan are put in the reading room by mistake, Natalia says. But they have to be more careful with books that include references to the LGBT community. For example, the book labelled 18+ “Summer in a Pioneer Tie” by Malisova and Silvanova (both ‘foreign agents’) is not worth the risk, despite the demand for it among readers. The librarians would rather write it off than hide it in the “closed” collection.

Since it allegedly promotes LGBT propaganda (‘the LGBT movement’ is labelled ‘extremist’ in Russia), if this book is accidentally found on the shelves, the library staff can be prosecuted for gay propaganda, Natalia says. So far the law doesn’t indicate any liability for displaying books written by ‘foreign agents’.

The library where she works has recently been renovated, young people have started to come in to work and check out the exhibitions, and it seems as if the attitude towards books has changed, there is more interest. Reading is now a luxury hobby, Natalia says, pointing out an article published by Vogue magazine.

“In my opinion, the authorities in our country are trying to hunt down everything living and good that suddenly sprouts up on our plains. So it’s obvious that both the authorities and concerned citizens have now started to take a closer look at libraries,” — Natalia explains the increased control over the sector she works in.

“They are afraid that they won’t get a chance to read them later”

The rumour about the looming law has already reached one of the university libraries in the North-West Federal District. And while the library management has not given clear instructions on what to do with the books of ‘foreign agents’, the staff themselves are keeping an eye on the Ministry of Justice’s list. As a precautionary measure, they constantly monitor the website of the department and check the electronic catalogue to see if any of the books in their system are on the list and need to be labelled, librarians say. They also regularly report on this to their superiors and warn their colleagues about the books that need to be removed from public access. But some librarians are in no hurry to take on that initiative.

“I informed a colleague that she needed to remove Lipsitz’s economics textbook from the catalogue. And she replied that she would do that only after she had an official paper on her desk,’ says library worker Ksenia**.

Igor Lipsits — a Russian economist, worked as a professor at the Higher School of Economics in 2001-2023. He created Russia’s first full cycle of school textbooks on economics. In March 2024, the Ministry of Justice added Lipsits to the list of “foreign agents”.

If a reader wants to take out a book by a ‘foreign agent’, it will be taken from the “closed” collection and given with a warning about the status of the author (if the reader is over 18 years old).

“For books kept in closed collections, we have added bookmarks labelled 18+ and with a note about the “foreign agent” status of the author. But this is more for us. We officially can’t label anything because we haven’t received any orders,’ Ksenia says.

Meanwhile, in municipal libraries in the North-West Federal District staff have already started labelling books out of their own initiative.

In the library where Ksenia works, there are more than a hundred books by ‘foreign agents’. The majority are works by Boris Akunin, Lyudmila Ulitskaya, and Dmitry Bykov. They were popular before, but recently, according to Ksenia, the demand for them has increased. “They are probably afraid that they won’t get a chance to read them later,” she says.

“Others, on the contrary, might refuse to read them to make a point, because the author is a “foreign agent”. It’s a personal decision. The main thing, of course, is not to go overboard with all these laws. Many books were written long before it all started, and it is unlikely that the author included anything illegal in there,” she says.

In the book industry, the whole “foreign agent” thing is being joked about whenever possible. “I have read books by ‘foreign agents’, of course. I read many of them even before the authors received this status. I find the law on foreign agents very silly, to be honest. They joke that declaring someone a foreign agent is the best recommendation. And that’s partly true. I was at a book festival in July, I took Arkhipova’s book, I went over to another stand, and the seller girl saw it and said: ‘We have books by candidates for the title of foreign agents. Let me show you,” Ksenia says with a smile.

Alexandra Arkhipova — a folklorist and social anthropologist, she’s on the Ministry of Justice’s “foreign agents” list.

But when it comes to Rosfinmonitoring’s list of terrorists and extremists, some Russians have already developed self-censorship. “Readers never ask for books by writers who are on the list of extremists, although before they were regularly being taken on loan,” Ksenia says.

Russian law prohibits the distribution of extremist materials, as well as their production and storage for distribution purposes. And if everything is more or less clear with “extremist” literature, the same cannot be said about the new law on ‘foreign agents’ (who may be not just authors of books, but also editors, publishers, illustrators, or simply write an introductory article).

The Russian Library Association said in a statement that libraries are to use the article of the Constitution on the right of citizens to freely receive information as a point of reference in their work, among other things.

“Libraries are keeping a low profile”

Recently, at national library conferences, special sections have been organised where the staff discuss what to do with the books written by ‘foreign agents’. For example, at the conference ‘Corporate Library Systems: Technologies and Innovations’ in June 2024 a whole round table was devoted to this issue, titled ‘Foreign Agents, Inventory or Verification: Issues to be resolved’.

However, the participants of the discussion did not understand how the forthcoming amendments to the law could be applied in practice. Tatyana Petrusenko, executive secretary of the section on the formation of library collections, said that of all the laws that restrict access to information, the law on foreign agents is ‘the most weakly motivated, poorly adapted to library activities”.

She mentioned that in Russia, prosecutors are already checking libraries, apparently for compliance with regulations that have not yet been adopted. “Russian libraries [in Yaroslavl, Vladimir, Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and other cities, Editor’s note] are now being inspected. <…> Prosecutors or their assistants are walking around with a list, Petrusenko explained. It’s a list of writers they [prosecutors] use in libraries to find foreign agents.”

A list of 38 ‘foreign agents’ can be found in free access on library websites. Compiled by the staff, it’s based on data from the Ministry of Justice. Some institutions, like the Moscow Provincial Universal Library, even issue a kind of ‘manual’ on how to deal with books by ‘foreign agents’. For example, they advise their colleagues to go to court if “a librarian or visitors to the library suspect that there are signs of extremist literature in the work of an author recognised as a foreign agent”.

When libraries ask for explanations from higher authorities, their questions are often ignored. “‘We often invite representatives of the Ministry of Justice or the Prosecutor’s Office to our library events, but they never come, precisely because they want to avoid giving any recommendations, especially when it comes to such, how do I put it, slippery and obscure issues like that of “foreign agents”, Petrusenko complains.

“We’ve been through this before”

Lilia** lives in the same Moscow suburb as Natalia, but works in a different library. She makes no secret of her negative attitude toward some authors-‘foreign agents’, but she condemns book censorship. “We’ve been through this before. We have already seen the “burning” of works by Gumilev, Pasternak, and Brodsky. So we shouldn’t do that. The content of these books is decent. Their behaviour not so much. But why should the books take the blame?” she argues.

She cited the works of two writers:

“Take Akunin, his books are very good, light reading. Need to rest? Unload your brain? Here’s some high-quality, good reading. Especially for those who like historical mysteries. I recommended them to everyone. Take Ulitskaya. Yeah, she’s talking rubbish now, but her writing is great, the language, the style. Try and find another author who writes like her”, Lilia says.

In recent years, the work of librarians has changed considerably. According to Lilia, now they have to be able to do everything: manage social networks, take photos, organise events. The time they used to have to familiarise themselves with new books so that they could give readers recommendations, has been cancelled.

The library room where Lilia works has been renovated. It has a new ceiling, flooring, windows and blinds. However, there was not enough funding for the walls and furniture, and the renovation itself took five years. The library is going digital: all books are being put into an electronic database, and now library cards have to be created through the online portal for State Services.

“The state has to know everything, what you eat, where you go. The state needs to know what your spiritual life is like and what you do for a living,” Lilia says with irony.

She is against digitalisation, because books are ‘too personal’, and the right to read in the library ‘should be unconditional’, not reserved for those who have a digital library card on the State Services portal. But Lilia doesn’t argue with her superiors about this.

“Here’s how it works: if you don’t like it, pack your bags, go to the train station, and look for a job elsewhere. They aren’t keeping anyone. Either you adapt in some way, enter this system, try to mould it to yourself somehow, with minimal losses for colleagues and readers, or you don’t work here,” Lilia says

The library in a small town in the Tver region doesn’t have many visitors, but there are regular readers, mostly pensioners and students. The former are often interested in love novels and detectives, the latter in classics and scientific literature. Oksana** got a job here as a librarian three years ago. The work is hard and the pay is low (the vacancy for a second librarian has been open for a long time), she says, but she enjoys the job and likes to be around people.

Once a year, together with her colleagues, she conducts an audit and writes off ‘obsolete’ and dilapidated books. Some of them end up on the bookcrossing table, but most of them are taken to the paper recycling centre. The ‘foreign agent’ books have so far been taken to the book depository.

‘It’s not only the writers who suffer.’

Olga** works in one of the libraries of a city with a million inhabitants. Because of an internal order, they have already gotten rid of the books written by ‘foreign agents’. As a precautionary measure, even bookcrossing was shut down: in case someone brought a ‘forbidden’ book and the librarians didn’t notice it in time.

“They sent us a list of books to be withdrawn, and [we] wrote them off as defective. What was done to them afterwards? They were taken away. Most likely, they were recycled. However, some staff members take them home, and it happens that readers steal books of ‘foreign agents’: they take them on loan and then don’t return them. Then they buy other books or reimburse the cost,” says Olga.

An employee of one of the libraries in the Vologda region said that she too had taken home several books of ‘foreign agents’, because she was afraid that one day they might simply be confiscated. The library management tries to act preemptively, they are not ready to take risks for the sake of books, but the librarians, according to Olga, find it very difficult to get rid of the works of ‘foreign agents’. This tension is due to the fact that libraries are run not by librarians but by managers.

“For him [the manager], the main thing is to avoid problems and keep his post, but the books’ value is quite vague,’ Olga says.

The books by ‘foreign agent’ authors were withdrawn from children’s libraries as well, as far as she knows. For example, Andrei Makarevich’s book ‘I am a snake’.

“It’s not just writers who suffer, but also illustrators and the whole team behind the book. I feel especially sorry for collections that contain one work by ‘foreign agent’ authors. We are forced to withdraw those copies too. Sane librarians realise that this is a big problem. There is no official order or regulation, and the value of the library’s collection is being destroyed with the hands of its staff,” Olga concludes.

**Not their real names.