In February 2023, the St. Petersburg-based «PMC Wagner Center», created by businessman Evgeny Prigozhin, hosted an exhibition of works by artist Alexei Chizhov. Titled «New Order», the show featured large-scale paintings depicting foreign mercenaries in opium poppy fields. Their message — an attempt to enlighten the viewer about the «dark side of American hegemony». This is not the first exhibition hosted by the «PMC Wagner Center»: alongside «New Order», visitors could see the photo project «Volunteers», and a little earlier — an exhibition organised by a pro-government motorcycle club «Night Wolves» called «War in Faces». But what makes Aleksei Chizhov different is that he is a contemporary artist, and the curator of his exhibition, Alexander Montlevich, is a philosopher and co-founder of the «Paideia School of contemporary art».

Over the past few decades, representatives of contemporary art have been assigned the role of the enemy, incompatible with traditional values, whose ultimate goal is to defy existing rules and corrupt society through Western influence. Hence, an alliance between a contemporary artist and an ultra-patriotic structure actively fighting in Ukraine would have seemed impossible until recently. Novaya Vkladka reporter Ivan Kozlov tried to find out what the Russian Z-artist community is all about and whether Chizhov’s exhibition marks the start of a new trend.

«I was delighted when I heard Putin’s call»

Most Russians don’t understand (or accept) contemporary art, which is often labelled as «liberal». Though, like in politics, the division is contingent, contemporary art continues to be seen as the antipode of «traditional» art (which is also formally modern but forbids any kind of experimentation with form and content). No need to examine survey results, the comments section of any article on the topic provides a whole range of the most common stereotypes. The average Russian, unfamiliar with the art scene, perceives contemporary artists as outcasts and perverts, who do nothing but chop icons with an axe, dress up monkeys as war veterans and, of course, use chicken for purposes other than cooking and eating.

This is hardly surprising, since for the last three decades contemporary artists, in general, have never sought to be understood or liked by the general public, feeling quite comfortable within the hermetic art environment. Society has often responded to this indifference, bordering on contempt and provocation, with protests, official complaints or vandalism, among other things.

The artists’ relationship with the state has also been bumpy: even during perestroika, their art was politicized and often oppositional. «It is important to note that in that period there was also a pivot towards a foreign audience, so a strong political context was expected from Russian contemporary artists. <…> The stereotype that contemporary art is an indispensable instrument of political struggle distorts the image of the entire sphere,» wrote sociologist Maria Makusheva. After February 2022, things took a predictable turn: protest art (and independent art in general) in Russia was purged.

Historically, Russian contemporary art has never been associated with anything «pro-regime» or «patriotic», let alone «pro-war». This is partly why Alexey Chizhov’s exhibition at PMC Wagner Center caused such a stir. Chizhov himself is one of the few exceptions to the rule. He identifies as a «Z-artist» and, according to fellow artists, has been faithful to his anti-globalization, anti-Western and pro-Russian views for years. Over the past 13 years Chizhov has displayed his work in over twenty exhibitions, in some of them he has raised political issues.

«Since the beginning of special military operation,» Chizhov told Novaya Vkladka in an interview, «as an artist and a citizen I stand in solidarity with the work of the Wagner fighters and support their military mission to protect and liberate Russian people in Donbas. It gives me great moral satisfaction to be able to conduct a special art operation in my small sector of artistic resistance and to contribute to this pivotal moment in our history through this new cultural institution.»

For Chizhov, anti-war sentiments in the art milieu are equal to treason and the artists who hold those beliefs are easily influenced cowards. Still, he notes that «not everyone has lost their mind somewhere in Georgia [editor’s note: likely referring to the anti-war artists, journalists and activists who have fled Russia since the invasion], even in this environment». He keeps in touch with those, but apparently, there are not many of them, and there doesn’t seem to be a «request from above» for their pro-Russian activity. Chizhov doubts that such a request is possible at all, based on his understanding of the nature of contemporary art. In his view, this strand of art developed as part of the processes of globalization under the watchful eye of the «American war machine,» while Russian artists attempted to integrate themselves into the system, seeking to make a career.

«It would be strange if they were not Western-oriented in doing so, he says. Now the destruction of this system has knocked the economic and moral ground out from under their feet. Offended, they blame the special military operation and Putin for this personal catastrophe. <…> In a way, it is even understandable. After all, they were raised to fit into that system in contemporary art schools, these ideological greenhouses. Now these greenhouses have collapsed and their residents have been thrown out into the cold reality, where they try to keep warm by producing something dissenting».

Chizhov, on the other hand, tried to create something pro-war, while taking as a foundation material which initially had no pro-Russian pathos. The exhibition «New Order» is actually not really new. He started this, as he himself calls it, «anti-globalization military-opium series» back in 2015, and the paintings first made it into the exhibition in 2018. Between then and the launch of the show at the Wagner Center, the series barely changed: only a few new works had been added. But the context has, and Chizhov is fully aware of that: «Since the president’s statements about Western colonialism, the series is fully in line with the foreign policy of the state. I was delighted when I heard these words and Putin’s call.»

Changes in the exhibition followed. In the previous version of «New Order, there was no mention of «American hegemony», and the whole thing could easily have been interpreted as «anti-militarist», reported online outlet Bumaga. Perhaps, however, this shift in emphasis is due primarily to the views of the curator who wrote the description text, philosopher and teacher Alexander Montlevich, based in St. Petersburg, who contributed to the controversy surrounding the exhibition.

«Boring subject»

«In Chizhov’s case, as far as I know, it’s a choice he made a long time ago. In the case of Montlevich, it’s a little more peculiar. Surely it seems like a ’fun experiment’ to him, and it’s certainly an act of defiance to the supposedly ’leftist’ community to which he previously belonged. I see it as something transgressive and self-destructive, a violation of some basic conventions,» says Maxim Evstropov, an artist, philosopher and activist, best known as the creator of the Party of the Dead.

He and Alexander Montlevich know each other from the Paideia School of contemporary art, where Evstropov, originally invited as a member of {rodina} group, taught a course on «political magic». He liked Paideia for its strange near-artistic practices like tulpamancy and ethnomethodology, but in its final years, the school was in permanent crisis. One of the reasons that led to the school’s closure was a stalking case involving a child and one of Paideia’s founders, Montlevich.

The story of Montlevich stalking an artist Maria Dmitrieva and her son for dubious purposes appeared online in February 2022. No legal consequences followed and Montlevich denied all accusations in a rather cliché way (saying, for example, that Dmitrieva envied his success), but many colleagues turned against him and he was effectively expelled from the «leftist community».

Alexander re-emerged in the public a year later, as curator of an exhibition at the Wagner Center, prompting his former colleagues to update the article about the stalking case with a disclaimer: «This news brings us back to the questions we posed a year ago: about the connections between different forms of violence, about the consequences of the lack of criticism and blindness of the art-theoretical community to a depoliticized and depoliticizing language and way of thinking».

«The apolitical nature of the liberal scene in the art world has led to quagmire, powerlessness, stagnation, conformism and systems of tolerance of any sort of nonsense,» says an artist familiar with the situation, who asked not to be identified for security reasons. A paedophile at the Wagner Center? Great, interesting! Have a look at the dynamics in contemporary philosophy and discourse in recent years, anything sound strange? <…> The exhibition [«New Order»] didn’t come out of nowhere; something preceded it and something allowed it to happen, almost without meeting any criticism. Because everyone was happy as a pig in shit at solo exhibitions at some Anna Nova

Montlevich sees his collaboration with the Wagner Center as consistent with the spirit of contemporary art and finds all criticism exaggerated: «The community has been promoting the theme of toxicity, using it, he said to Novaya Vkladka. If we look at if from the point of view of a ’citizen of the world’, then contemporary art itself is a toxic substance whose ’dark side’ does not defend any didactic values but plays on the dialectics of the negative side of human existence».

The fact that Montlevich doesn’t seem to have a rigid personal stance supports Evstropov’s version that the curator was driven by personal motives. On his Facebook* page Montlevich wrote early on that he would not comment on the war in Ukraine.

«Well, I just don’t comment, that’s it, he told Novaya Vkladka. I think that nobody cares about my opinion and I do not care who and what others say. I don’t comment on the topic of abortions either, or on capitalism. I think there are many topics that don’t require everyone’s opinion to be heard, and I think the special military operation is one of them. It’s a boring subject. There is not much to say about it».

When asked about how he views his new curatorial experience and the ensuing public reaction, Montlevich answers dryly: «Four out of five»

Total mobilisation of the spirit

«If you look into post-ironic statements in contemporary art or, for example, in literature, it turns out that they often have a reactionary undertone in some sense and end up benefitting the authorities,» says Naila Allakhverdieva, curator and head of the PERMM Museum of Contemporary Art. Though she’s not talking about Montlevich specifically, her words seem to apply to him, too.

Regardless, it’s unlikely we will ever know to what extent the actions of the former Paideia teacher were driven by post-irony, «fun experiment,» careful calculation or a desire to finally separate himself from his former social circle.

The motives and views of the other protagonists featured in this article are far less ambiguous. Among them, Alexei Belyaev-Gintovt, perhaps the most famous and sought-after ultra-patriotic artist in contemporary Russia, stands out with his particularly rigid and categorical views. Belyaev-Gintovt has participated in more than a hundred exhibitions and went to Paris on scholarship; his works are displayed in many museums and private collections in Russia and abroad. With more than thirty years of experience, he has acquaintances in various circles. All things considered, he could have had a successful international career had his ideological views not bound him to Russia so tightly.

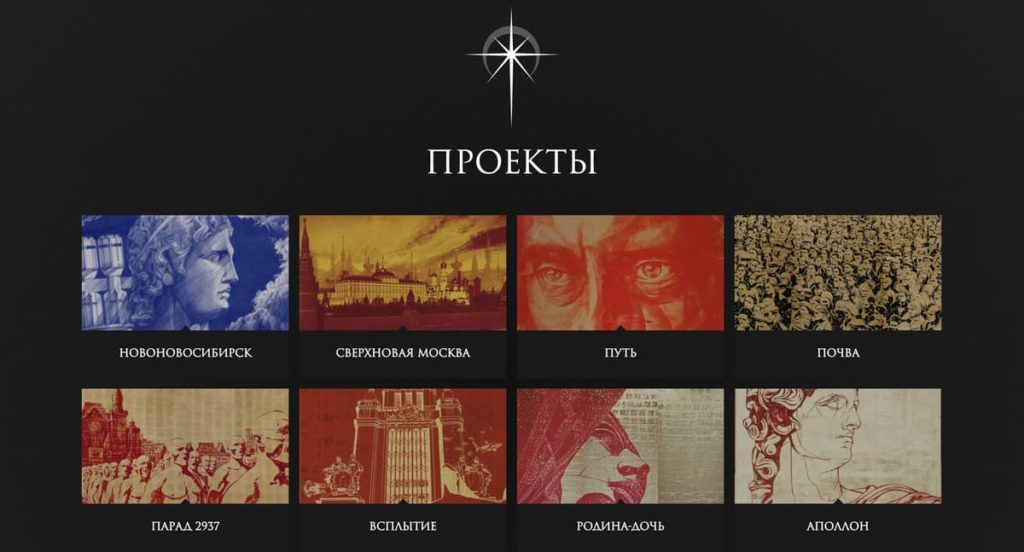

Belyaev-Gintovt’s style can be described as imperial avant-garde and, thanks to its ostentatious pomp, can hardly be confused with anything else: his red-and-gold canvases depict starships in the form of the Kremlin stars, endless lines of topless soldiers, or futuristic Moscow landscapes, defying the laws of physics. Aside from his art, he made a name for himself as one of the most active associates of the philosopher Alexander Dugin and the stylist for Dugin’s political parties «Eurasia» and «Eurasian Youth Union».

«The project of contemporary art originated across the ocean, says Belyaev-Gintovt. It is a strictly Anglo-Saxon phenomenon. The decision-making centre is there, where the masters of discourse are, the rest of the world for them is a periphery».

According to the artist, the West sees this project as future-oriented and treats it as a field for exploration. But when applied to Russia (the territory of «occupational democracy»), it has the opposite effect: free search is suppressed and loses its meaning, and contemporary art in the domestic context becomes the field of «generation of alien meanings, which are by principle opposed to us».

Having been integrated into the system of national contemporary art for many years now, Belyaev-Gintovt does not consider himself a loner behind enemy lines, but he does not see any signs of the nascent «patriotic» project either. «Alas, not a single sign. As for the demand for its implementation — it is immense and comes from the peoples of our country. It is important that the peoples address the authorities, bypassing the elite, but, in my view, there is neither a direct address by the peoples nor a response signal today. These two metaphysical dimensions have not met yet. I know many people, I have the privilege to be present on many floors [in power structures]: there is nothing there. For now, there is nothing there».

At the same time, Belyaev-Gintovt has calculated that since 1991 the country has produced no less than 50 thousand trained artists (he is referring to the accumulated 30-year supply of art schools graduates, as well as those specialising in jewellery making, architecture and other «creative» professions), in addition to roughly the same number present before the collapse of the USSR. That makes, by a very rough estimate, about a hundred thousand. All of them work in one way or another, notes Belyaev-Gintovt, but they have neither a unifying idea nor channels of communication that allow them to get to know one another and coordinate.

The latter problem, he suggests, could be solved by administrative authorities: «I have come to the conclusion that the only way to catalogue one hundred thousand authors is to entrust the job to the domestic security services, because no one else can do it. Ideally, we should offer them 100 working opportunities in the civil, military-civilian or military fields. Of course, no one will be forced to do anything — only by choice».

As for the lack of a common idea, the way out, Belyaev-Gintovt believes, is even simpler: mobilisation. In this case, «mobilization in the spirit»: «This idea, feeling is shared by almost everyone, the total mobilization in the spirit is being discussed, but still there is no sign of it. The whole territory of the country is the rear and the line of contact with the enemy is the frontline. But there’s no sign of the formation of a ’country turned home front’ either.

The artist regrets that the authorities never declared total mobilization, and on the contrary, did everything to make sure that the life of those «behind the lines» after February 24, 2022, did not change at all. It looks as though there are whole headquarters somewhere, dedicated to maintaining the illusion of a peaceful life, Belyaev-Gintovt says. He hopes that in a moment of need these headquarters will switch to martial law just as successfully and professionally.

«Let all flowers bloom — money, swastikas, crosses»

Art, in theory, should also be completely militarized, but in recent decades the «masters of discourse» have made every effort to ensure that none of this happens, says Belyaev-Gintovt: the enemy was proactive and all alternative directions of thought in contemporary art were «ruthlessly suppressed».

To prove his point, the artist turns to personal experience. In 2008, he received one of the most important awards in the field of contemporary art, the Kandinsky Prize, causing major scandal and backlash. Not only in the media, where headlines like «Can a far-right nativist receive the Kandinsky Prize?» appeared before the jury’s final decision but also offline. At the Winzavod exhibition centre in Moscow, where the prize was being awarded, left-wing activists organized a protest, holding banners with slogans «Let all flowers bloom — money, swastikas and crosses» and «Kandinsky’s ashamed!» Belyaev-Gintovt calls the discussion surrounding the situation «bullying like Russia hasn’t seen over the past ten years».

It seems that over the years, presenting certain awards or awarding grants to right-wing and ultra-patriotic projects has become the norm and has ceased to surprise (but not outrage) anyone. However, Belyaev-Gintovt does not feel that the number of his like-minded colleagues has tangibly increased during this time. The lack of attention and incentives from the state certainly shows.

«That’s just the way contemporary art is presented in contemporary Russia, it is still perceived as something peripheral, regardless of how far it has come over the past 20 years, argues Nailya Allakhverdiyeva. And of course, there is a state order for patriotic work, but it is not being delivered in the field of contemporary art, that’s impossible, rather, in the field of street art. Street is a space where there is no expert control between the artist and the public, it is a resource for populists».

Overall, Maxim Evstropov agrees with this opinion, confirming the absence of «huge interest», but disagrees on the details.

«On the one hand, he says, I don’t see any demand for contemporary art from the state and Russian society as a whole at all. On the other hand, „pro-Russian“, right-wing or right-conservative, contemporary art is a long-standing trend, with its own local traditions. And I would not say that this trend is insignificant».

Evstropov gives an example, of New Academy, founded by the late artist from St. Petersburg Timur Novikov, who took a conservative turn in its art in the early 1990s by becoming an adherent of the «ideals of classical beauty» and opposing classical art to modernism. He amassed many supporters and followers, but according to gallery owner and curator Marat Gelman, who also brings up Novikov, they did not succeed.

«Timur Novikov is a genius, says Gelman. He chose to oppose Moscow as a part of the modernist world, made it his artistic strategy and built his own philosophical idea. All totalitarian movements like [New Academy] lean towards academism, in the sense that they focus on the past».

According to Gelman, Novikov’s followers (among them, for example, Belyaev-Gintovt and Sergei «Africa» Bugaev) made a mistake by trying to make a movement out of his personal game, not realising that what might work as a personal strategy in art, won’t work if replicated. As an example, Gelman cites the «dog-man» Oleg Kulik, who made a point of opposing European culture: «You think we are wild, so I will be wild, I will bite». As a personal strategy, this is successful, but it is obviously impossible for all art to become like Oleg Kulik. The same thing happened to Novikov’s followers: not a single interesting phenomenon came out of their return to the academic ’golden age’«.

Maksim Evstropov notes that in today’s Russia, it is not the right-conservative art but the left-wing and critical contemporary art that is far more removed from the mainstream. Every day it is becoming more and more difficult to work in that field, and it is not just because of military censorship.

«The current art system in Russia, including museums, galleries, major regular exhibitions, is very conservative and dependent on the state, he explains. A couple of years ago some institutions could still follow the example of the Western critical leftist liberal agenda: feminism, decolonisation, environmentalism and the like. Now all of it is meaningless. Some continue to maintain the appearance of an artistic life as if nothing had happened, while others try to conform to the new right-conservative agenda.»

It makes sense that conformists are emerging in the artistic milieu, ready to cooperate with the authorities, Marar Gelman believes, and the exhibition at the Wagner Center is an example of this. «But if they become part of the cultural system, after a while they themselves will be unmasked, because when it comes to language, these people will still remain strangers to the authorities, says Gelman. So perhaps there will be a purge <…>, the second year will be marked by the authorities rejecting and exposing their conformists».

On the whole, according to Gelman, contemporary art cannot become «patriotic» because in many ways the interests of the state and the artist are opposite: any artist, even a conservative one, dreams of fame, while today the state can only offer isolation from the world. The artist needs freedom, at the very least to be able not to worry and constantly monitor the fluctuations of the «general line».

«It’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery wrapped in an enigma, shrugs Belyaev-Gintovt, when asked about the formation of the community of „art-patriots“. But, obviously, I have like-minded people in the plastic arts field, we work on common projects, too».

For example, in 2014-2015, in collaboration with artist Andriy Iryshkov, Belyaev-Gintovt created a series of videos to be used as splash screens for Donetsk television channels. They were rejected not only by Donetsk TV, but also by Russian TV channels Zvezda and Spas.

«The metaphysical realm of the good»

Indeed, if a community of contemporary Z-artists even exists, it clearly has issues with unification and self-presentation.

Shortly before 24 February 2023, Alexey Chizhov posted information about an exhibition by an unknown group ArtFraction Z on his social media. The opening was supposed to coincide with the anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine. The exhibition is titled «Time Z». The abstract read: «We believe that Russia is a metaphysical realm of goodness, a special country where the heavenly city of Kitezh stands forever. The artists demonstrate the essence of Russia’s strength and explain why it will never be defeated.»

Who is behind the mysterious «we» remains unclear. Following a conflict between the curators, and the exhibition was cancelled. In any case, according to Chizhov, a new venue for it is yet to be found in Moscow, and the structure of the exhibition remains a mystery, as does the list of participants.

Dmitry Pilikin, curator and art historian, who has had the chance to engage in discussion with Chizhov and his associates in the comments section of Facebook posts, claims that the artist has formed a kind of circle around him, with its own exhibition policy, whose members actively discuss ideological opponents.

«There’s another dude in the circle, who recently became known to the public. He deliberately went to Finland, got support from Artists at Risk foundation, and then came back and wrote an ’exposé’ about European bureaucrats», says Pilikin.

The «dude» Pilikin is talking about is artist and musician Yaroslav Troyansky.

Troyansky’s work is inherently ironic. For example, a decade or more ago he created a sculptural composition entitled «The Cossacks Spit in the Face of Marat Gelman». The work was inspired by real events: in May 2012, at the opening of the ICONS exhibition at the Krasnodar Exhibition Hall, the Cossacks actually spat at Guelman. To be precise, one person did the actual spitting: Father Alexis, senior priest of a local church, but Yaroslav Troyansky rejected documentary precision in his sculpture. Instead, he focused on the technique: the artwork is actually a sort of a fountain, so the Cossacks figures literally spit at Gelman with one press of a button.

Troyansky explained that his artwork «reflected the current situation in cultural politics in a slightly humorous way,» and noted that over the past ten years it has «taken on new meaning.» He now speaks negatively about Gelman: «From his house in Montenegro, I suppose, he distributes that NGO money, opens his mouth, saying what they tell him to say on YouTube — what a bore». He does give credit to his sense of humour, though: at some point Troyansky gave the sculpture to Gelman, and it was displayed in the Vinzavod gallery for a long time. However, before leaving for Montenegro, Marat returned the sculpture, either because he did not want to take unnecessary cargo with him or because he no longer found the joke funny.

Gelman no longer remembers neither the incident, nor the artist: «Perhaps Envil Kasimov introduced us, but for me that’s not relevant. Now the only relevant thing is: who will be able to get out of this? The young, I think, will make it out by themselves and become part of the European cultural machine, while the older generation is my burden, let’s put it this way.»

Troyansky himself has no interest in being helped to get out of Russia: he has already taken a peak into the European cultural machine, and he didn’t like it.

«There will be more war»

Yaroslav Troyansky is one of the members of the notorious ArtFraction Z and the failed patriotic exhibition. The former, he says, includes several dozen widely known artists, photographers, writers and journalists, whose names he, like Alexey Chizhov, does not name. But Troyansky himself is a proud member of the ArtFraction Z and rightly so: he describes his current position as unequivocally pro-Russian. This has not always been the case.

«In 2017, due to some changes in the laws, my business went bad I became miserable, deep inside I blamed the government and external circumstances, and then liberal rallies started happening, explains Yaroslav. I just got pulled into the movement, but not too much; I did not rise up in the ranks, thank God, but I could see for myself how well the liberal/western propaganda was put together».

Influenced by liberal propaganda, Troyansky stopped educating himself and went from reading books and long articles to scrolling social media, he admits. He might have gradually morphed into a diehard liberal if not for a trip to Finland in the first half of 2022, which was like a «vaccine against liberalism and globalism».

The Artists at Risk Foundation, which considered Troyansky an artist at risk of persecution in his home country, invited him for an all-expenses-paid residency. After a while, Troyansky came to the conclusion that what the inviting party needed from him was not art, but a biased, Russophobic «narrative». Outraged, he returned to his homeland, wrote several social media posts supposedly revealing the truth about the foundation and participated in a press conference at the Patriot media centre.

Such a categorical and abrupt turn from liberalism to patriotism is not common even among artists. However, Troyansky claims that everything happened in good faith: «Initially, it wasn’t any sort of provocation, and I didn’t know it would turn out this way. But in the end, there is providence, and I’m happy with everything that happened to me. It’s an important experience.»

So far this new pro-Russian and patriotic attitude has not been directly reflected in his work, but it has added a new meaning to his paintings: the artist is now working on interpreting his own family history. This includes his maternal grandfather, who fought in the Second World War, and his maternal great-grandfather, the captain of the naval ship «Red Vostok», who was shot in 1938 and later exonerated posthumously in 1958.

According to Troyansky, there is a demand for pro-Russian contemporary art in modern society: «On the whole, people are fed up with the same type of evil bullshit, he says. Greyscale images of wooden toilets next to the inscription ’Russia’. The problem with Western art, which is made and funded by NGOs and eventually by the intelligence services of the US, England and parts of the EU, is that it is monotonous, boring, its objective is to mock something or someone. It follows one given theme, and that theme ends up being funded as complex propaganda. And the Russian idea is about space, spirituality, faith, telepathy, all kinds of yoga, nature, God.»

Troyansky believes that many contemporary artists today hold a pro-Russian position, but are as yet unable to say it openly because the leaders of contemporary cultural institutions are still «Western» for the most part. However, the situation, in his opinion, is changing: «We were all glad to see the changes that started happening, like the expulsion of Tregulova and Loshak».

The artist describes Chizhov’s exhibition at the Wagner Center as a manifestation of «intellectual punk in a stiff and hypocritical contemporary art environment». Troyansky is confident that the number of those kinds of exhibitions will only multiply over time.

«It’s clear that there won’t be less war, says Belyaev-Gintovt. Nor will it be the same as now. It will only expand, which means that our discovery is as irrevocable as the sunrise, as our victory. I am sure,» he says rhythmically, «the enemy will be defeated, victory will be ours!»