Knowing that tomorrow you’ll go completely mad, forgetting the names of your children, smearing shit on the walls of your room and getting lost on your way to the bakery – these might sound like scenes from a movie but are real-life scenarios for someone with advancing dementia. Our reporter wanted to know what it feels like to live alongside and care for someone with that diagnosis.

The original piece was published in June 2024.

Russia is ninth in the ranking of countries by dementia rates: according to the Russian Ministry of Health and scientific gerontological communities, two million people in the country live with dementia. The condition takes away a person’s memory, the ability to think and speak rationally, and to perform the simplest household activities. It changes the patient’s personality. As overall life expectancy continues to increase, dementia rates growing exponentially: according to WHO forecasts, the number of cases will triple by 2050. Dementia patients are usually cared for by their relatives. Meanwhile, 25% of Russians don’t know what dementia is and how to behave with a sick relative, according to the Russian Public Opinion Research Center survey. Because of the stress associated with the disease, 10% of those having to care for relatives with dementia consider suicide. About 80% of dementia cases are associated with Alzheimer’s disease, and a person can live with that condition for up to 20 years.

Novaya Vkladka interviewed people who became carers for their relatives with dementia, whether driven by ethical reasons, sense of duty, need for money, or love, in an attempt to find out how they are coping with a sense of guilt, self-blaming and stress.

“Not the kind of relationship you can get out of”

In 2021 37-year-old Masha Antipieva from Omsk, an employee of the city administration, was bawling in her therapist’s office. She came to confess that she wanted to kill her 94-year-old grandmother.

Masha was named after her grandmother, Maria Ivanovna Kravchenko. For the last two years, the two lived together, divided only by a wall. At night, her grandmother would scream from the top of her lungs, for half an hour or longer. After catching her breath, she’d scream again. During the day, The old woman would throw food at Masha. She could scoop up mashed potatoes with her hand and smash the lump right onto her granddaughter’s chest. Or she could pour the soup on the floor and throw the plate at Masha’s head. She called Masha a “whore” and a “slut.”

In 2020, Maria Ivanovna was diagnosed with vascular dementia. But the “weird incidents” started before that.

One day Masha was fiddling at the stove and arguing loudly with her husband. Her grandmother walked into the kitchen wearing just her nappy, took a fork from the table and stuck it into her granddaughter’s husband’s shoulder.

In 2021, Masha’s husband left. He couldn’t stand it, all of it: the fork, the naked grandmother, the screams, the smell and, as he said, “crazy shit”. Masha had a hard time going through the divorce and took depression medication. She had to take care of her grandmother and put up with being constantly called “whore”, scraping mashed potatoes from the walls and sleepless nights. When Masha couldn’t take it anymore, she would grab a sock off the drying rack and hit her grandmother with it. Maria Ivanovna became afraid of the sock. She developed a conditioned reflex, like a dog: as her granddaughter would reach for the sock, the old woman would calm down.

Dementia is a condition that affects the brain, killing the brain cells. It’s an irreversible process. Each stage has different symptoms, but it always involves a disruption of cognitive functions: remembering, thinking, understanding, speaking, and the ability to move in space. Someone with dementia cannot control his or her emotions, often cries or screams, shows aggression, forgets things, gets confused and “lost” in another reality.

Dementia is caused by diseases and injuries that cause brain damage, such as Alzheimer’s (the leading cause, responsible for about 80% of all dementia cases) or a stroke. As of today, there is no treatment for dementia. A person’s personality changes, in the late stages dramatically. But patients can still live for many years, though not without help: at some point they lose the ability to care for themselves, leaving their family to care for them.

The therapist listened as Masha told her how a quarter of a century ago her mother had been working her ass off at work, her father had left, drinking himself to death. Her grandmother was the one who brought her up. In the 90s, her grandmother saved the family from starvation by renting out her flat and moving in with her daughter, who had lost her job, and her granddaughter. She ploughed her garden at the dacha, planted potatoes, sold cherries and red currants in summer. At home, she baked pies from virtually nothing, “a handful of flour and a pile of haulms”, and twenty years later Masha still remembers their taste. Her grandmother handmade all of Masha’s clothes, sewing skirts using old fabric scraps.

Masha loved her grandmother. And now she was saying the word “kill” out loud.

She was lucky to find a therapist.

“Usually, therapists are not particularly happy to see us, relatives of dementia patients, says 44-year-old Evgenia Melnikova, whose grandmother also suffered from dementia. This is not the kind of relationship you can get out of, even with a struggle, in an attempt to change your life strategy. You are literally bound to your dementia-afflicted relative; without you, they will die because they will not be able to care for themselves”.

At first, Maria Ivanovna’s daughter Tamara, Masha’s mother, cared for her.

“I hoped she would die of cancer.”

During the time that she lived with her daughter, Maria Ivanovna’s temper kept deteriorating, Masha recalls. She would get offended if she thought her granddaughter hadn’t said hello when she came to visit. The soup was cooked the “wrong” way, potatoes were too bland, onions were overcooked. This infuriated Masha: “She just wanted to get under my skin” and her mother cried regularly. Masha says that her mother was terrified of Maria Ivanovna, “to the point that she could squeal like a rat”.

Once Masha’s mother bought a vegetable dryer and hid it in Masha’s flat: she was afraid to tell her own mother that she had bought an expensive item without telling her. Because of pancreas problems, Maria Ivanovna was told to follow a diet, and she would scold her daughter if she saw her eating a cake or meat “to spite her”. As a result, Masha’s mother basically stopped eating at home.

A dementia patient develops an accentuation of premorbid personality characteristics over time, and the leading traits become stronger, says Tatiana Ivanova, a psychiatrist, Doctor of Medical Sciences, and an expert of the largest Russian social project on dementia MEMINI. A thrifty person becomes greedy. A restless person turns into a pathologically anxious one.

Maria Ivanovna was strict, according to Masha’s stories. She was a commander for her own daughter Tamara. When Masha would break a toy as a child, her grandmother would beat her with a belt, put her in a corner if she disobeyed, and hit her on the lips if she didn’t like her tone. Masha was allowed to hug and kiss her grandmother twice a year: on her birthday and on Victory Day.

The disease made her aggressive. “She used to drive my mother mad! I feel like mum got cancer and died so that she no longer had to live with her”, Masha says. In 2018, two months apart, both her grandmother and mother were diagnosed with breast cancer. Both of them at inoperable stages. “I hoped that she, my grandmother, would die of cancer, says Masha calmly. Well, I mean…Yes, I hoped so! Because it’s impossible to live like this all the time…”

But her mother died first, three years earlier.

“On the day of my mother’s funeral, I witnessed my grandmother going mad with my own eyes,” Masha says. She recalls Maria Ivanovna being lifted into the hearse. She said her goodbyes. It was the last moment when she still remembered having a daughter.

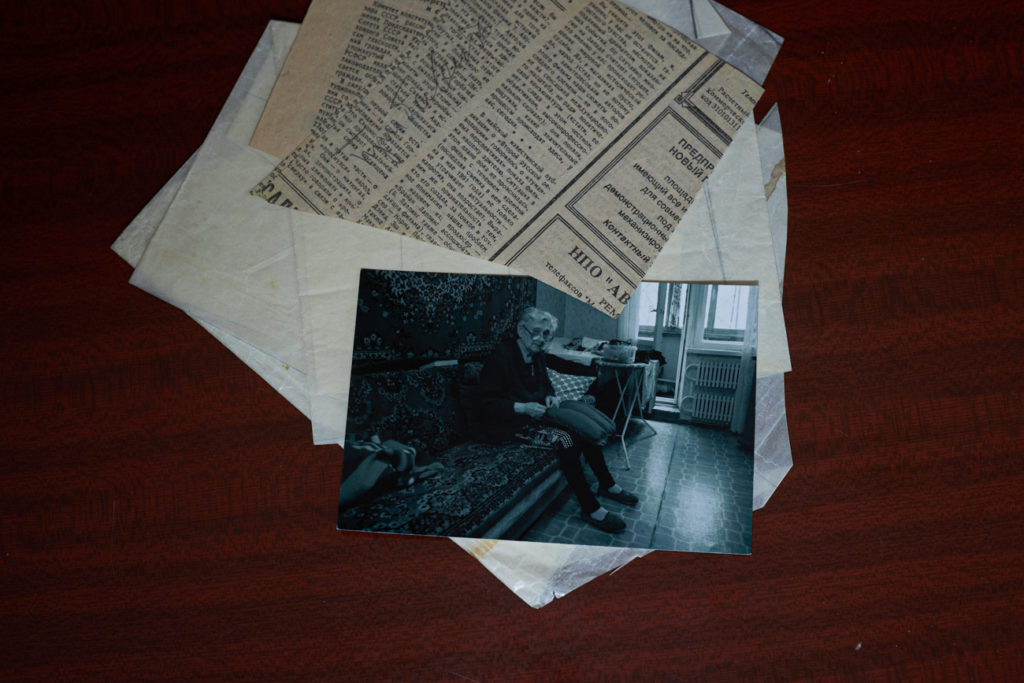

Masha realised this when flipping through a photo album with her grandmother the day after the funeral. Looking at a family photo, of herself, her husband, and her daughter, Maria Ivanovna asked: “Who is that next to me? Who’s the baby?”

She never remembered her daughter Tamara again.

This is one of the manifestations of dementia in its late stages. There are seven stages in total. In the first two there are no obvious symptoms, although changes in the brain are already taking place. An average person is not able to notice the changes in time. At the last stages, those affected are no longer able to eat, dress and wash themselves independently, they start seeing things and hallucinating. In the final stage of the disease, the person is completely disoriented, loses speech skills, ceases to control defecation and urination, sleeps a lot during the day, and stays awake at night.

More and more often, Maria Ivanovna looked at Masha with “glassy eyes”. She started screaming at night. “Until you come face to face with it, you don’t understand it. And even when you do, you still don’t understand,” says Masha.

She plays a video she filmed for the doctor: deep in the night, the grandmother starts listing all the dead people she remembers by name. And then she screams from the top of her lungs. Masha’s pets, a dog and two cats, terrified, get into her bed. The four of them (Masha included) hide under the blanket. “Luckily we have no neighbours to the right and left in the stairwell”, Masha says. On nights like this, Masha would sob into her pillow, and sometimes also start screaming.

After a few months of her grandmother behaving either like a “vegetable” or a “tank”, Masha called a psychiatrist. The doctor explained that Maria Ivanovna had vascular dementia, put her on the register, and prescribed her pills. He explained that this was merely supportive therapy.

Psychiatrist Tatiana Ivanova tries to explain dementia “for dummies”. During a stroke or trauma, brain cells are massively damaged. Neurotransmitters, a “highly evolved chemical soup”, are released and in search of a new “pot” try to get inside a healthy cell. “They tear it up from the inside and move on, like an army,” Tatiana says. The drugs help build a fence around the healthy cell. But if a person stops taking these pills, the fence collapses, the huge enemy army instantly starts destroying cells, and within a week, the patient forgets how to take off his trousers”.

Even if the right treatment is prescribed on time, there will be no miracle: the disease will get worse over time. Therapy can stabilise the disease, and slow down its development, but it is impossible to “jump” back a few stages and stay there forever. Dementia is always a one-way ticket.

“But nobody knows how fast the train is travelling, Masha says Only the final destination is known, but there is no schedule. It’s worse having a child or a dog! A puppy pees on the parquet floor, but you can teach it to pee outside. A child yells and wets his pants, but he’ll grow up, learn to use the potty, and start talking. This is degradation and hopelessness. It’s hell, and you get used to living in it”.

Pills made little difference. Soon, Maria Ivanovna forgot her granddaughter, too. She knew that Masha was someone who lived with her but didn’t know that it was her granddaughter. If Masha explained it to her, Maria Ivanovna could keep that memory alive only until she fell asleep. When she woke up, that knowledge was gone.

“Gradually I got so fed up with everything that I had no strength left for fear, Masha says. I stopped sleeping, and I didn’t care who was alive, who was dead, or who was going to die tomorrow. I just wanted it to be over so I could get some sleep”.

She’d caught her 94-year-old grandmother masturbating a couple of times. Sometimes she would find her scrutinising the contents of her nappy with her fingers.

“The whole thing was a shock to me”, Masha says. The most difficult thing is to get used to the fact that your grandmother, mum or dad are no longer there. “He or she looks like your loved one, but it’s a different person. You’ve always known and loved them — but not this version of them. You’ve always been loved by them — but a different them. How do you even come to terms with that? How do you accept it?”

An “embarrassing” disease

The stories of people whose loved ones suffer from dementia are very similar: first, they attribute the strange behaviour of their mother, father, and grandfather to age and bad temper, and then they blame themselves for not recognising the disease in time.

Our reporter talked to ten relatives of people with dementia and also studied thematic forums. Despite the fact that life situations may be different, all these people describe the same feelings and emotions. The stress, the frayed nerves, the shouting, the crying, the scandals: there is no answer to the question of how to act to avoid feeling guilty. Those who remain close to such patients blame themselves for the almost inevitable breakdowns, for their inability to change the situation, for caring for the dementia-affected relative to the detriment of their own family, partners, and children. Or, on the contrary, for choosing their own lives over becoming the caretaker.

On forums and social media dementia patients are referred to as “dementors”, blind creatures from the fictional Harry Potter universe that feed on human emotions, sucking out a person’s soul. Masha Antipieva says the metaphor is very accurate: “This disease sucks the joy and life out of relatives, who become caretakers”.

“Screamed. swore, broke a chair, then sobbed”; “I am eating myself alive”; “a persistent feeling of guilt for the fact that I can not do it all: take care of my grandmother, children and work”, “I go in a vicious circle: irritation at my mother, guilt, helplessness, and then all over again”, those are all messages posted online on forums about dementia. Participants of support meetings at the alzheimer-cafe “Nezabudka”, which are occasionally organised across Russia by charitable foundations, talk about the same thing.

These people feel they are in an emotional vacuum: emotional support is just as hard to find as physical help. “Dementia is an “embarrassing” disease, you can’t talk about it with friends over dinner with wine, and you can’t invite a friend to visit because yesterday your grandmother smeared shit on the walls. People are irritated by dementia,” Evgenia Melnikova, who attended one of those support groups, told Novaya Vkladka. She has been caring for her dementia-stricken grandmother for two years.

The relatives of dementia-affected patients in Russia have three other options: to hire a carer, to send their loved ones to a state-run psychoneurological facility or to a private care home. A psychoneurological facility is, in fact, a state-protected facility, something between a hospital and a prison. There are few private care facilities in the country that take in people with dementia. Those are mostly located in Moscow and the Moscow region and their services are expensive, as well as the services of private live-in carers. When faced with that decision, one becomes hostage to several factors at once: personal and public ethics, finances, sense of duty, and feelings towards their relative. Whatever the decision, the feeling of guilt is unavoidable.

“First you care, you feel pity and anger, but after a while, you get tired and callous. That’s it, you’re a robot! It’s either her or me, that’s how I feel right now” – reads a post written by Ekaterina, who put her mother in a special facility. “Was it a relief? No, guys. A soul-burning decision. Pain, tears, dreams, fighting the urge to take her back immediately. But it made my family, my child, feel better. I was so overcome by my daughterly duty and love for my mother, I forgot that there were still people who needed me”.

The situation is equally agonising for those who live far away from their elderly relatives. “When I am on the phone to my mum, she dies eight times every hour. She is difficult, prone to depression, hysterical, manipulative, and with the disease it all became more acute. She stumbles over her words, walks at night, and she’s all alone in the house almost half the day, until the carers come. A neighbour has seen her fiddling with the gas, getting confused with the knobs. I am scared of both leaving her there and taking her in. I have a family, a job. We decided to put her in a special facility. Everyone’s judging us for it,” another online user admits.

Psychiatrist Tatyana Ivanova also points out the complexity of this dilemma. It’s better not to move elderly patients, as moving is a huge shock to them, and their condition deteriorates sharply, she says. At the same time, she emphasises, a person in a state of severe dementia can indeed be dangerous to themselves and others. “They can open a window and step right out,” she says.

On forums, people share their stories of having to hide knives, forks, scissors, utensils, and ropes from their relatives. Still, it doesn’t give them peace of mind: “they guard the wardrobe, bite and scratch”; “she knocked on the neighbours’ doors, they called the police”; “she tried to give a child her pills”; “he eats faeces”; “he keeps asking to kill her”.

“The person you knew, with whom you shared memories, ceases to exist. This is the scariest thing. They’re not dead, but they’re gone,” 52-year-old Anna from Omsk, who is caring for her parents, confesses. Both of them have dementia: the father’s dementia is barely perceptible, while the mum’s has been progressing for eight years. Anna is an accomplished top manager, currently in charge of a sanatorium, her nickname at home is “Colonel”.

But even her iron stamina gives in, and “Colonel” cries. She tries hard not to scream when her father refuses to take a shower, or when her mother wants to go out for a walk at midnight. The best advice, in her opinion, was given to Anna by a classmate whose mum had lived with dementia for six years. She said: “Watch your language. If you lose your temper, you’ll be in trouble! Your mother won’t remember or understand, but you’ll remember and then you’ll hate yourself.”

“I hated myself for hating her”

Often, even when a person with dementia dies, the guilt of whoever cared for them remains. Relatives can neither forget nor forgive themselves.

Maria Ivanovna Kravchenko, Masha’s grandmother, died in 2022. The first time Masha cried was only a week after the funeral.

“It’s been two years now, but living is still hard for me, she says. It’s as if I left my whole self there. I have no strength for a child: neither to give birth to my own nor to adopt one. I have no strength for career ambitions. For a long time, I couldn’t do ordinary household chores. I didn’t throw things away. One evening I threw out a binder with five years’ worth of copies of “Healthy living Herald”, and at night I ran out and took it back. My grandmother’s dementia broke me too: I hated myself too deeply for hating her”.

Since then, she thinks she has had”something like Tourette’s syndrome”, a neurological disorder in which a person can involuntarily twitch, make sounds or swear. Masha swears often and a lot, she says.

“When my grandmother was sick, I wanted to break furniture and smash dishes. Sometimes at night, she would scream, and I thought: I’ll kill you now, bitch, shut the fuck up! I physically restrained myself and it all came out with swearing. I still haven’t weaned myself off it, Masha admits that she even swears at work. If you listen to my voice messages to my bosses, I swear too”.

It was at that same time that Masha stopped caring about what she ate: she had no energy left to cook, but she needed energy. She resorted to ready-made food: sushi, kebabs, shawarma, pizza, she’d “devoured tonnes of it”. While caring for her grandmother, she gained more than 20 kilos.

When her husband left and she remained alone face to face with her grandmother’s illness, Masha decided that she would channel her aggression into finding a new man. She created a profile on ten dating sites and left her information at a marriage agency. “I started looking for a husband like a madwoman. But really it was sublimation, a defence mechanism. It became an obsession and a second job for me”, she recalls. Every day Masha would meet up with or chat with three or four men.

Over a year and a half, she went on 74 dates. On the 15th, 37th and 59th she received marriage proposals, but she didn’t like the prospective grooms.

On the last one, the 74th, Masha met Dmitry. The man was determined to create a family, was also fond of fishing and mushroom picking, and loved the countryside. A week later Dmitriy moved in with Masha and for five months he helped her look after Maria Ivanovna, until her death. It’s only when a man came into her life, Masha says, that she felt a little better and “began to accept the situation”.

Masha, a philologist by education, got another degree as a clinical psychologist to help those who, like her, had to deal with the dementia of their loved ones.

In May 2024, 45-year-old Elena Yevstigneeva, along with her mother, came to her workshop in Omsk.

“Empty-headed”

74-year-old Lubov Yevstigneevs hasn’t been officially diagnosed yet, but all her symptoms point to dementia. She has started forgetting names and things, confusing events, and having visual hallucinations. In the near future, her daughter is going to take her to a psychiatrist to get therapy that will allow her mother to cope with cognitive impairment.

Lyubov Ivanovna is aware that “something is wrong” with her. She is both scared and not scared: “It’s like when you watch a film, she explains. You see something scary, but it’s not real”.

Lyubov Ivanovna says that she was really scared three times in her life. The first time was forty years ago, when she, a lab technician at a thermal power plant, was returning home from a night shift and was attacked by a man who yanked her bag off her shoulder and ran away. The second time was in the 90s when she was made redundant and left alone with her two daughters, while her husband had left and was living with another woman. The third time was when her daughter told her that her granddaughter, Nastya, was born weighing just 620 grams, had cerebral palsy and was being taken to an ICU.

And now, even though she knows how dementia progresses, she is not afraid. Because — well, how could you believe it? “Although I, of course, I have become empty-headed,” she adds.

Once, she left her keys at someone’s house but didn’t realise until three days later. Another time, she bumped into a former colleague on the street, and wanted to call her by her name, but realised she didn’t remember it. She went to the shop on the eve of her birthday, carrying a pair of new shoes in a bag (her daughter had given them to her). She bought a cake and brought it home, but the next morning she realised that she had something else with her, a bag, but no clue what had been inside. She went back to the shop and couldn’t remember why she had come there. She asked the salesgirls: “Girls, do you recognise me by any chance?” They recognised her and gave her back her bag. “Double joy! As if I was given these shoes twice,” Lyubov Ivanovna laughs.

Another time at the supermarket, she had picked up some waffles. While walking to the till, she decided that one pack wasn’t enough. When she went back for the waffles, they were gone. She had just seen them there, and now there was toilet paper and washing powder. Within minutes, she had forgotten where the waffles were. She went around the supermarket but still didn’t find them.

Two months ago, Lubov Ivanovna woke up one morning and saw a woman standing in the doorway. “I got up and followed her. I checked the second bedroom, the balcony, and looked through the window. I went all over the flat and she wasn’t anywhere.”

She also noticed that has gets offender very easily these days. “I feel like my daughter has become angry. I get upset, I start crying. But I don’t know whether it’s really the case or it seems so to me…” And then she says that in general, her children (her daughters and their husbands) love her “with all their hearts”. They bought her a bicycle, for example.

“Mum has always been easily offended, and this has become more acute. It’s like walking through a minefield: don’t say this, don’t say that, that’s bad,” says her daughter Elena. She became worried when she noticed that her mum started to repeat the same thing several times, that she stopped taking care of herself as she used to, forgot to brush her teeth, and began to shower less often. Her house became dirty. Once she came to Elena’s house and walked into the kitchen with her shoes on.

“We fight every now and then. Sometimes I don’t spare her. I snap, I burst into flames: what a diva! A queen! When I cool down, I apologise”, Elena says. Her 12-year-old daughter Nastya, who has cerebral palsy taught Elena great patience, but her mum still manages to drive her mad. “Sometimes it’s like a vampire has sucked me dry,” she says.

Elena, a preschool teacher by training, mostly takes care of her daughter, but not only. She works, has a stylish wardrobe, a fresh manicure and not a single grey hair, largely thanks to her mother, who helps her with Nastya every day. The greater the challenge, the more powerful the “counterbalance” should be, she believes. When Nastya was born, Elena signed up for salsa and bachata lessons. When her mum started having memory problems, she took up ballet.

A year ago, when one of her colleagues was putting her dementia-stricken mum into a state-run psychoneurological facility, it became clear what she would do if her mother became very ill and could no longer live on her own.

“I can’t judge, everyone has their own path. But I can’t do that. How can I pay her back with this kind of ingratitude? There was an option for my mum to stay with us, we talked about it with my husband. I thought she’d live with her younger sister and I’d help out. But I haven’t talked to my sister about it, I’m procrastinating… It’s bad! I may need some therapy”, Elena admits.

“Don’t be afraid, my girl. All this horror shouldn’t happen in my case, says Lyubov Ivanovna, shaking her head, as she pours tea. How can I possibly forget your name? Or forget my way home? This will not happen,” she says, hugging her daughter and putting two spoonfuls of salt in her tea.

According to the WHO, there are about 10 million new cases of dementia registered worldwide every year, which is becoming the leading cause of disability among the elderly population. Global pharma companies are still failing to develop drugs that treat the main cause of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease. In 2018, Pfizer announced the closure of one of their projects because they could not prove the effectiveness of their findings.

At the beginning of 2024, psychiatrist Tatiana Ivanova had a patient come in who was just 41 years old. She believes that COVID and the geopolitical environment have made a significant contribution to the development of neuropsychiatric disorders: there are more and more of them and the patients are getting noticeably younger.