The human rights project OVD-Info was founded in 2011 to help those arrested during mass protests, the biggest since the fall of the USSR. Today, it counts more than five thousand volunteers. They not only process appeals from people participating in mass protests, but also perform many other tasks: from transcribing audio recordings and doing research to editing and translating articles, providing IT support and doing graphic design. The project received the highest number of applications during the 2019 summer protests, after the opposition politician Alexei Navalny returned to Russia and was detained in 2021, and after the start of the war in Ukraine. “New Tab” reporters spoke to OVD-Info volunteers and those they help. It was inspiring.

The original piece was published in July 2024.

In 2021, OVD-Info was included by the Ministry of Justice on the ‘foreign agent’ register. To ensure the safety of the project participants and those they have helped, we decided not to disclose their names.

My first time participating in the protests was in 2019 when journalist Ivan Golunov was detained. We organised “Solitary Pickets” at Gostiny Dvor in St. Petersburg, and police officers politely checked our documents. At that time I already knew about OVD-Info, but I thought: they must be receiving so many applications during mass protests that even if I was detained somewhere, I would reach out to them, for sure, but I doubt they would answer.

In February 2022, I was no longer in Russia, but, like many people, I wanted to do something. And on February 27th I was already on duty at my first OVD-Info shift. At that time I was struck by how smoothly everything was running, the amazing warmth and support of the coordinators, and the regular reminders to call back on missed calls and respond to all messages sent through the bot.

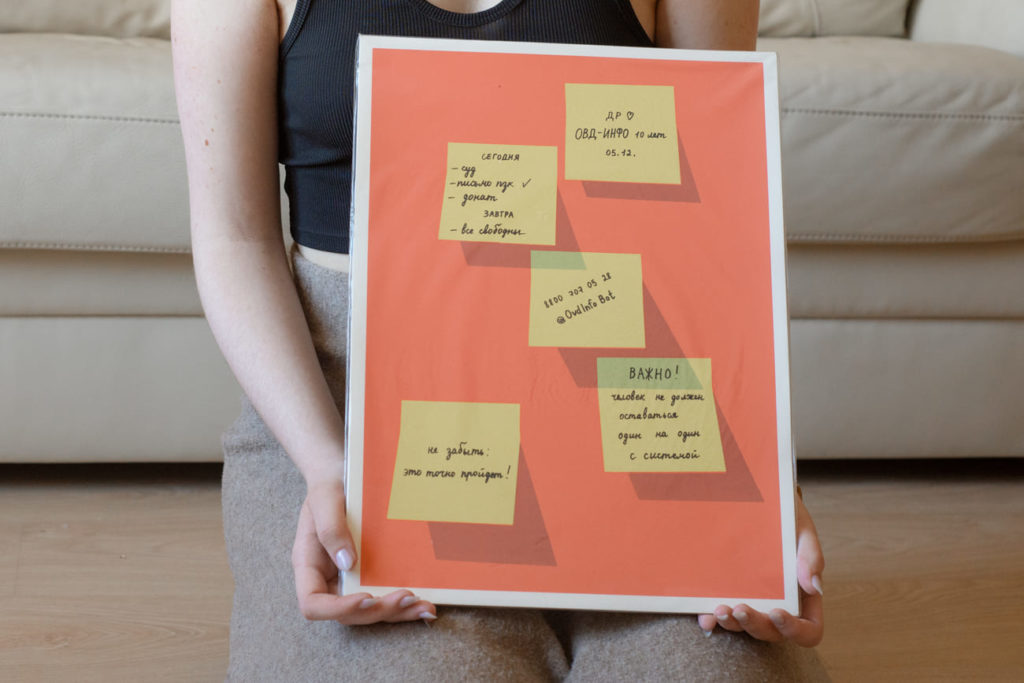

No request goes unanswered.

No one should be left alone to face the system.

At the time, I felt like I was among superheroes. And two years later, I want to tell you about them: what they do, why they chose to volunteer and what their hopes are for Russia in 2024.

The human rights project OVD-Info, which helps those who were detained during protests, has been around for 13 years. It has a 24/7 operating hotline, and its lawyers help people at all stages of detention: from the moment of detention to appealing a court decision. The website and social networks of OVD-Info feature tips and instructions with practical information: how to protect yourself on the Internet, how to behave at a protest, what to do if you are detained or if the police come to your house.

OVD-Info also works as a research centre: it monitors persecution on political grounds and tracks law violations around demonstrations. According to the project’s data, the peak of detentions at public protests in Russia was in 2022: 20,441 people were detained at 1,909 rallies. In 2023, 953 protesters were detained across 506 demonstrations. Since the start of 2024, 1,061 detention cases have been registered so far.

Volunteer — a person who helps the project without getting paid.

Volunteer coordinator — a staff member who oversees the work of volunteers and assigns tasks.

Lawyer/defender — a person with a legal background who is being paid by the organisation to help detainees; some lawyers specialise in human rights, others get involved during large actions when there are not enough permanent defenders.

A hotline or simply “line” is a telephone number using which detentions are reported; usually one of the staff members is on duty.

Bot (for detainees) — a text-based analogue of the hotline, a Telegram bot that you can text if you have been detained (or if you are going to a protest and want to give a heads-up).

Bot (for volunteers) — a bot where coordinators communicate with volunteers and distribute tasks.

HQ — the emergency mode during large-scale protests, when there are not enough staff members. Volunteers then go to the bot and take up shifts on the hotline to collect information about hundreds of arrests. The shift usually lasts a few hours; the headquarters mode can last for days or weeks at a time. But for the past two years, as the mass protests have winded down, headquarters have been happening less frequently.

L., a volunteer

L. has been volunteering with OVD-Info for several years; after the start of the invasion, she worked for a while as a staff volunteer coordinator.

L. first decided to volunteer after talking to her friends who were already helping the project, she saw their calls to action and joined. Now L. edits and translates articles, but what she enjoys most of all is being on duty at the headquarters during mass protests:

“It’s so hectic in a good way. Everyone is very involved and something is happening in real time. You help and see how your actions affect the lives of specific people: here you are registering a request through the bot, and an hour later a lawyer is heading to the police station.

L. admires the inner workings of the organisation: everything is very coherent, despite the huge volume of tasks. When asked why she thinks this is the case, she replies: “Because it’s run by the right people. People who do what they are good at doing. And the values they share. Values alone are not enough in a project that’s aiming to help people: the whole thing will fall apart if crucial skills are lacking. And skills alone are not enough either. But together, it works.”

Many volunteers at the headquarters are scared of working on the hotline and answering calls. L., on the contrary, went straight to the hotline.

“My first reaction is to take on the most difficult tasks because in the moment I get this feeling that if I don’t do it, no one will, she explains. So it’s not scary, it just needs to be done, I feel”.

If their phones are not taken away in the detention centre, the detainees are rather calm: they call and provide the details of everyone around them. Sometimes they sound excited: they went out to protest, they knew that they were likely to be detained, and it happened, the deed is done. Some have a defensive reaction, others are genuinely not afraid, and for some, it’s not the first time. Many know what comes next: if it’s the first detention, at worst they’re facing a few days in detention.

“You can get used to it, L. adds. At some point what used to scare you no longer does”.

Friends or relatives of detainees may call to inform the volunteers about the detention or to find out information about their loved ones. They tend to be more frightened. The important task of the hotline operator is not only to collect information but also to reassure the caller.

L. herself has never been detained, but many of her friends have. She knows well what it’s like to wait outside the courthouse for hours at a time, especially in winter. Once she was on duty at the headquarters, when a friend of hers was arrested. L. was following what was happening to him and remembers how difficult it was to prioritise between her friend and other people who also needed help.

L. is about to graduate from university, in her free time she does yoga and fitness, paints, and studies the Scottish language. L. is also involved in the city’s Zabeika intervention project. Zabeika is a small bench that is placed on a low fence and turns it from a dividing element of the city into a unifying one. Today, the collective creation of Zabeikas is perceived, among other things, as a good reason to gather a large number of people on the street and not get arrested for it, L. says. They get together, cut down pieces of wood, and paint them; even if a policeman asks them about what they’re doing, they can say: it’s a group clean-up.

Volunteering has taught L. to be braver: if something scares you, you just have to get on with it and do it. Being in dialogue with others is crucial to her: to be able to express one’s opinion, but to remain open to a different point of view.

S., a detainee

S. was detained in St. Petersburg at a mass protest on Saturday after the start of the war in Ukraine. A column of protesters marched from Gostiny Dvor down Nevsky Prospekt; at one point, riot police began to separate the crowd and squeeze everyone onto side streets. It was a very well-organised attack, S. says.

S. ended up on Liteyny Avenue, near the bookstore ‘Podpisnie Izdaniya’, next to a woman who had just come down to the shop to get a book. The riot police lined up along the road, buses were brought in, and everyone was ‘packed in’, about 60 people inside each bus, packed to the brim. “I’ve never been in a real police van, which is a shame,” S. jokes.

The bus set off straight away, but it took a long time to get there: in the city centre, the wards were full, so they were taken to Krasnoselsky district. They got to keep their phones, so everyone was reachable, sending the names of the people on the bus to OVD-Info, monitoring the situation.

One of the detainees, a ‘cool, charismatic dude,’ as S. describes him, was telling stories the whole way, and at one point he opened OVD-Info’s description of “a perfect detainee” and read it out loud. And in bits where the instruction described things that the police had no right to do, he would turn to them and say: “See? You have no right to do that”.

It felt like those who detained them were ‘ideological’: they were tough, and while they were waiting at the police station, asked ‘Why are you even doing all this?’, S. recalls. But the staff at the police station were more annoyed that they would have to work all night (‘poor them, of course,’ S. says, grinning). The police officers were also struck by the mutual support and coordination: the detainees were brought small packages, water, and there was a general mood of mutual support: where did all this come from, why are they so eager to help each other? While the officers were drawing up protocols, everyone was waiting in the big hall, sharing their experiences of previous protests.

S. was not informed about his trial ahead of time: he received a call from a private number, informing him that the court hearing would take place in two hours in Krasnoselsky court. S. even suspected he was getting scammed. The woman on the other end of the line got angry.

S. immediately informed OVD-Info that his trial had been scheduled. That day, OVD sent over a defender on duty to the police station, and S. wasn’t going to go to the trial anyway, as he knew he could be arrested for the crime he was being accused of (obstructing the movement of public transport and violating COVID-19 norms – everyone was accused of the same thing, although the protesters only walked on the pavements). As a result, S. received a fine and filed an appeal, as per OVD-info instructions.

When the war started, S. first realised what anxiety was. “The feeling that something terrible is happening and there’s nothing you can do”, he says. So going out to protest wasn’t as scary as doing nothing. S. is a scientist. “I am the kind of person who is comforted by knowledge”, he adds. Before taking part in the protests, he read through the articles on OVD-Info several times, on how to behave properly, what to do, and what he could and could not be threatened with. This gave him comfort and helped him to avoid doing things that could lead to more serious consequences.

Having a lot of people share your views, that in itself is a very powerful support system, S. says. He was surprised that OVD-Info was willing to help him appeal a court decision. “It makes you feel that you are not helpless before the regime, but that you can do something. For a person who has never even been to court, this whole system feels overwhelming, you don’t know where to go, or what to do. But with their help, you feel supported, if something goes wrong, you can fight back”, S. says.

D., a volunteer

D. has been volunteering with OVD-Info for about six years. She chose the organisation because ‘they had the clearest and most transparent structure’. She does many things, from drafting appeals to the ECtHR to working shifts during large protests.

D. recalls the times before the pandemic: back then, most of the volunteers were in Moscow, and the headquarters were offline, “now, it’s a bunch of chat rooms, but back then people gathered in one room and worked, and no one came to knock on their door”. In St. Petersburg, volunteers managed to gather once or twice.

D. feels the need to do something for other people. “If I didn’t do it, I would feel worse”, she says, even though she is very sensitive to aggression and violence. Through the bot, volunteers also receive reports about rude, abusive detentions, so working at headquarters is difficult for D. “No matter how much you try to shield yourself, it’s impossible. But I guess headquarters is what saved me when the war started. Because I didn’t have time to think about myself, it was easier to sit and cry over other people [who were detained]. The worst thing is that we’re talking about a big flow of people and detentions, shit was going down, and for many, it was their first time. These people haven’t even seen police officers before, except for on the street”, D. says.

D. works in consulting and jokes that her job is to help big corporations make a lot of money. But she adds that since the start of the war, there has also been a social mission in it: for example, to make sure that the company doesn’t lay off three thousand people at once. In general, D. says, if she didn’t have to make money, she would do something more socially relevant. “I know what I want to be when I grow up, she jokes, but in our country, they put you in jail for that”.

When the war broke out and everyone started to leave, D. also almost emigrated in the first two weeks. What stopped her was the thought that not everyone would be able to leave anyway, and the most vulnerable, those who needed help the most, would be left behind. “Who hasn’t thought of leaving? But I don’t think I’m that old yet, I can obviously live to see better days”, D. says.

D. can’t even imagine her life five years from now, she admits. Life has changed a lot in the last two years. “It’s kind of crazy, she worries. The laws, the repressions, everyone knows about that. But I look at the businesses I work with and see how people and their approach to decision-making have changed. It’s as if the business went back to the nineties. Someone can just come in and ask: what if we just let everyone go and not pay them? Looks like everyone is willing to just close their eyes, just like in everyday life: pretend you don’t see the problem so it doesn’t exist”, D. says.

She admits that she is frightened by her own reaction: the way she got used to violence because it’s impossible to continue to engage and react. “It’s a normal defence reaction, tolerance increases, but it will all come back to bite us”, she concludes.

A., a lawyer

A. found out about OVD-Info from his girlfriend, who has been helping the project for a long time. When the war started, he realised that there would be protests and detentions. He wanted to help in some way and filled in the application form. OVD-Info was recruiting legal defenders at that time. He had an interview, everyone was given a big manual, added to the chat rooms, and immediately distributed between the courts. “It was quite something,” A. says.

He recalls the first weekend after the war started: lots of detentions, huge numbers of people in the courts, it was very cold. If someone was detained on Friday, they would be taken to court on Saturday, but no one knew what time, so the defenders were on duty from ten in the morning and were often they not allowed inside.

When you’re a defence lawyer after mass protests, you don’t know ahead of time how many defendants there will be, A. explains. There are some lists, and estimate numbers. If one of the detainees has a phone, the hotline volunteers can find out how many people have been detained and which court they are being taken to. But it can also happen that there are five defence lawyers in the whole court, and a hundred people are brought in. The detainees are brought in, they sit down to wait for their sessions, and the defence lawyers are allowed to talk to them.

A. would come up and introduce himself to everyone, give instructions and forms, explain how to fill them out, and how to appeal court decisions. It didn’t matter which detainees had contacted OVD-Info, some didn’t know about the organisation at all, but everyone was offered help. Some refused help, though, saying they would rather not argue with the court, that they would rather wait until the trial was over so they can be sent home.

A. works in a firm that deals with bankruptcies. In ordinary courts, he says, unless you take criminal cases, “there is not that much bullshit on the legal side”: when you are right, you cannot lose a case. In cases of detainees from protests, it is different: police officers write anything they want in detention reports, even without knowing the name of the person they detained, while judges say that “there are no grounds to distrust police officers”. One of A.’s defendants had someone else’s surname in his report, and he was still arrested for a few days.

A. calls himself an optimist and says he truly believes that everything will be fine because things can’t be bad all the time. He is waiting for the moment when the political situation will change and though there will still be some police officers, and judges, they will have to follow the law. Then, A. says, they will have their revenge. A. also hopes that with the change in the political situation, the level of overall professionalism in the courts will grow.

In his free time, A. watches TV series, plays board and computer games, shooters and war simulators are his favourites. A. is against violence in life, but in games, it gives him adrenaline. “I always say: if you want to kill, go play, let all your demons out, that’s it’, A. says.

T., a volunteer

T. started helping OVD-Info in August 2019, when mass protests erupted after elections to the Moscow Duma. T. was living in Moscow at the time, and some of her friends were already volunteering. Recently, “you go to the headquarters chat room, and see thirty messages in a row all from the people you know”, T. says.

T.’s first task at OVD-Info was to call all the detainees and propose them to appeal to the ECtHR. “At first it was super weird: I remember the first calls when I just sat in front of my laptop and kept saying to myself that I would count to twenty, press the ‘call’ button and everything would be fine”, T. says. At first, she thought she didn’t know how to do anything, but at least she could call and talk with people following a script. After a while she realised that this was exactly what she was good at: she has a soothing voice, she can comfort, she can talk to people when they are angry. T. has done other tasks, like translations, but says she feels best and most confident when she works with people “just as small” as she is.

On 24 February 2022, T. went straight to the protests. “Inside me, I was hysterical, I had to go there, to Gostinka, otherwise I’d burst and explode. When I was detained, it was almost a relief”, T. recalls. Everyone’s phones were taken away, but T. pretended to need to call her mum so she could call OVD-Info and relay the details of the detention.

“Mum, don’t worry, I’ve been detained, they’re keeping us overnight, here’s the number of the department, love, kisses”, T. said on the phone. The girl on the other end asked: “Do you know who you’re calling?”, but she clicked towards the end of the message. And then things went differently: T. was released the next day, her phone was given back to her, and she found that her data had not been entered anywhere. None of her relatives knew where she had been, and based on the database, everyone was released immediately.

T. dropped out of the university after almost all the good teachers in her field were fired (although some of them held ‘underground’ seminars for students even after their contract was not renewed). Recently, she too was fired from a public school, where she worked as a tutor, because of disagreements within the team.

She can only make plans for the month ahead, T. says and jokingly calls her outlook on life “a sparrow’s view”. “I let smart people with political science degrees speculate on how things will go, but I don’t know anything, I don’t hope for anything, I’ll just do my little things and feel a little more useful”, she says.

N., a detainee

We met N. in the courtyard of the Fountain House in the centre of St. Petersburg. N. calls herself a book dealer: she works for a small publishing house and in a bookshop.

Her activism journey began with “solitary pickets” in 2020 when the government was making amendments to the Constitution. N. says that “it was scary” and she decided to protect herself by informing the OVD-Info bot that she was going out on another picket. She was never detained. “Either I’m an old lady or I picked the metro stations where nobody cared”, she says. But she kept the habit of informing volunteers. Besides, she had a good feeling after talking to OVD-info representatives.

The first time N. was detained was at a rally at Gostiny Dvor in the first days after the start of the invasion. They detained everyone who was there and brought them to the police station. Then the police asked who among the detainees was older than 55 (N. was among them), and told them to get out.

In the summer of 2022, N. started hanging posters, and pieces of cardboard with inscriptions or peace symbols. She made sure there was no one on the street, especially the police, but at one point she was detained by a police officer in a civilian car. When N. was brought to the police station, she immediately informed him that she would not say anything without her lawyer. “Are you talking about OVD-info?”, the officers asked her and their enthusiasm “went down immediately”. They didn’t take away her phone, so N. called the hotline, and a defence lawyer was sent to her: “A boy in his thirties helped me a lot, drew up a statement, he was so good and respectful”, she recalls.

The defence lawyer advised her to wait and not pay the fine right away, to appeal for its cancellation or reduction. In the end, the amount was reduced, but a year and a half later, N.’s bank card was blocked, so she still had to pay the fine.

When the fine is transferred to the Federal Bailiff Service, bailiffs can arrest bank cards until the debt is paid.

N. put up cardboard posters on trees, which she ‘chose as her accomplices’. She also photographed what others were doing: writings on the walls, stickers, and little toy picket figures. “It fascinates me, it’s a sign system. The city has to speak,” N explains.

Now N. is trying to keep a low profile. The most important thing is to keep her dignity and maintain ties with her loved ones. N. adds that she has become much more tolerant: before she could break off a relationship because someone was not speaking out, whereas now she values connections with people much more. And it is necessary “to do something beautiful, peaceful, something you love if you have an opportunity”, N. says.

O., volunteer

The main tasks O. takes on at OVD-Info are writing, editing, proofreading, and doing research, including court databases and systems. Thanks to her law degree, she easily navigates the legal jargon.

When the war started, what helped her most were walks with her dog, those 50 minutes in a swampy park, in the snow, which would not melt for a long time that spring. Around that time she came across a chat room “St Petersburg on the way from Ukraine to Europe” for refugees from Ukraine, which regularly shared information about collections and requests for help. O. gave away a lot of children’s things and clothes, stuff that was just taking up space in her house but could be useful for others. O. says that it helped her to keep going, the news was “bloodier” back then, or they were simply not used to it yet.

Today volunteering at OVD-Info became a huge comfort for O. She recalls going to the park on May 9th [Victory Day in Russia], everything was decorated with flags, and tension was palpable in the air. She came home that evening and worked on one of her tasks, and felt better. She took on another task in February 2024, on the day of Alexei Navalny’s death, at one o’clock in the afternoon. At four o’clock she messaged the bot: “Can it be one o’clock in the afternoon again, so that I don’t know that he’s dead, and I can work in peace?” They offered to push the deadline, but she refused. On the contrary, being in touch with fellow volunteers and doing meaningful work is what helps her best.

“In my heart I want everything to be fine. I think everything will be, but we don’t know when, and now we have to do what we can to make it happen, O. says. It’s 2024, not 2022, we have to have some kind of planning horizon again. But if you don’t want to fall into apathy or depression, you have to minimise outside influence. People who think like you, share your values, it’s such a comfortable social bubble, a way to take care of yourself”.

O. often listens to interviews and podcasts on her walks, and participates in monthly meetings of OVD-Info volunteers with guest speakers. When the organisation invited a podcaster who talks about scientific discoveries as a speaker, O. watched the meeting together with her daughter. O. appreciates situations where her work, hobbies and family time overlap. “It’s like you’re in the right place at that moment”, O. says.

I., a volunteer coordinator

I. lives in Europe and combines two jobs: as a volunteer coordinator for OVD-Info and as a scientist who teaches and does experimental science. I. says that being a volunteer coordinator gives him a sense of fulfilment and meaning, he doesn’t understand how he lived without it before.

Many things at OVD-info simply couldn’t function without the volunteers’ help, I. says: “Even when the volunteers make a big mistake or miss a deadline, we are still grateful for their help”.

Sometimes it can be difficult, a lot is going on, and it feels like everything is falling apart, but I. notes that even in those situations, “it never occurs to anyone to be toxic”. He calls it unspoken consent: some people want to help, others want to give them the opportunity to be helpful. That’s the most important thing.

There are times when volunteers turn out to be people that coordinators may know from other parts of their lives: from listening to their podcasts and to messaging them in the bot that allocates tasks. Coordinators and volunteers only communicate via chats, but those still have a personal touch. Coordinators sign with their names, and everyone has a slightly different style of communication. In the first six months of work, he saved 50 sticker packs in Telegram (that’s the maximum limit), spotted in conversations.

I. notes that people often look at what is happening in Russia from a position of pain and trauma. It seems that there is not enough energy, not enough resources, but it’s as if no one noticed how much has been done, and by quite a few people. There’s a huge number of volunteer organisations across Russia, and their number has only grown since the war started: the big actors have disappeared, but dozens of small regional ones have taken their place.

Anyone can become a volunteer for OVD-Info: some tasks don’t require special skills, such as doing research or transcripts. There are a lot of volunteers now, so it’s especially frustrating when five people are needed for one task, but ten respond, and they have to say “no”. Or when people write that they haven’t received any tasks for a long time, and they want to do something.

Recently, volunteers helped OVD-Info translate the project’s information materials into 18 languages of the Russian republics and countries of the former USSR. After that, someone wrote to the bot: “Thank you! I didn’t know how to answer a policeman in my native language, but now I do”

I. and I have been friends for many years. When the war started, I was not living in Russia, and he was already working at OVD-Info. At that time I really wanted to do something, to help in some way and to make myself busy with something. I asked him if he needed help and if I could volunteer. He immediately gave me an application for fill-in, instructions, and then wrote: “It was unexpected and timely, as if you were at my shoulder right now”.

Since then, I’ve been receiving messages in my volunteer bot with project outcomes and new tasks. The messages often end with phrases like “you are strong and gentle”, “live the spring”, “tomorrow is summer, be happy in it”, and “stay in love”.

I rarely take on new tasks these days, but every time I read these messages I think about a few thousand volunteers who read them and smile. And stay in love.