In the autumn of 2022, after capturing Kherson in Ukraine, Russia started evacuating its residents, most often through Crimea to the Krasnodar region. More than 100 thousand people were brought over, some of them then went on to other Russian cities. The authorities promised to pay them lump sum payments and provide certificates that could be used to buy housing. But some of those who were evacuated never received them.

Reporter Valeria Shustval went to Kuban to find out how Ukrainians, robbed of their homes, now face Russian bureaucracy and empty promises in a foreign land.

This story is published in collaboration with Govorit NeMoskva

The original piece was published in May 2024.

“Mum told me: the war has started”

32-year-old Alexey grew up in a large family in Kherson, which he describes as a small provincial town with a bunch of Khruschev-era apartment blocks in the centre. Until February 2022, Alexey worked part-time as a courier and ran a small coffee shop at the local market. He lived with his elderly mother and grandmother in a rented flat. He usually slept until lunchtime. That is, until the morning of February 24th, 2022: at 4 or 5 AM Alexei’s mother woke him and told him that the war had started.

Alexei recalls that it was cloudy and cold that day, it was about zero degrees outside. He got dressed and went outside to have a look around. Somewhere in the distance explosions could be heard, and aeroplanes and helicopters were flying around. In his half-awake state, disoriented, he smoked a cigarette, returned home and went back to sleep. Meanwhile, his mother and grandmother started packing.

“Back then, I didn’t realise the scale of everything. When I woke up around noon, as I usually did, my mum had already packed all the suitcases and the rucksack. The seaport was not far from our house, so we ran over there to the basement,” Alexei remembers.

On the first day of the war, things got really scary closer to the evening: the explosions intensified, and their sounds were louder and clearer. Many people, mostly women and children, gathered in the basement. As soon as the noises outside would die down, the bravest would run out of the shelter home and get valuables, food and water.

For the next six months, while Kherson was under the control of Russian troops, Aleksei, his family and other locals lived on the run between the basements and their homes. When it was quiet, people returned to their flats, cooked, and spent as much time there as possible. But soon enough, explosions would make them run back to the basement.

Alexei persuaded his mother to leave because he feared for her life. He himself stayed in the flat with his grandmother: because of her health issue, she couldn’t go anywhere, and she needed someone to take care of her. Alexei’s three sisters and two brothers still live in Ukraine, in other cities, further away from the front line.

“I told my mum: “Go wherever you can get to”. People were being evacuated, there were buses going towards western Ukraine. I didn’t really care where she went, because the explosions and shooting were very loud. She went to Germany. She lives there now, on her own, she has already settled in. She is not exactly young and getting used to new things is hard. But there are a lot of Russian speakers there, she’s settling in, she says she’s fine now,” Alexei says.

Four months after the start of the invasion, his grandmother died. When things got a little quieter in the summer of 2022, Alexei started working again. In addition to the coffee shop, he and his friends opened a few cigarette shops at the market. By that time, many shops in Kherson had closed, and some of them had been looted. On the morning of September 11th, Alexei received a message about an urgent evacuation to the left bank of the Dnipro River.

In the autumn of 2022, shortly before abandoning the city, Russian troops organised the evacuation of Kherson residents. Soon after, Ukrainian forces regained control of the city.

He packed up some of his stuff and documents and went to the evacuation site on the riverbank, it was not far from his place. From there, people were being taken across the river on ferries. On the left bank, buses were waiting for them, ready to take them to different cities in Russia. Three days later Alexei boarded the bus Alyoshka-Anapa. That was the beginning of his journey as a refugee.

Alyoshki – a city located near Kherson on the left bank of the Dnipro river. Until 2016, it was called Tsyurupinskiy.

Mess with certificates

In the autumn of 2022, tens of thousands of people were evacuated from the Kherson region to Russia. They were eligible for a certificate to buy housing and a lump sum payment of 100 thousand roubles.

The amount listed in the certificate, which could be used to pay for housing, was calculated based on the number of family members and the cost per square metre – 88,737 rubles (before indexation – 83,420 rubles). One person was entitled to 33 square metres, two people – 42 square metres, and a family of three or more – to 18 square metres per person, meaning that, one person could get 2.9 million rubles. The money came from the federal Territorial Development Fund.

This programme was cancelled in December 2023, and in April 2024 authorities stopped accepting applications for payouts. Over the course of the programme more than 20 thousand Kherson residents became house owners in Kuban, reported the vice-governor of the region Andrei Proshunin.

In September 2022, Russia held a referendum on the annexation of part of the Kherson region, so the refugees were considered Russians, though not all of them had had time to change their passports. This was not a problem at first, but in the summer of 2023, the conditions for issuing certificates got stricter, making only residents who had obtained Russian citizenship eligible.

On Telegram, there are several channels with thousands of subscribers, where refugees from the Kherson region share their experiences with receiving certificates and payouts. It turned out that getting a certificate does not equal buying a flat. At the buying stage, people were subjected to more checks. On Telegram, people called it “filtering”.

Before receiving a housing certificate, refugees needed to collect a bunch of documents to submit to the municipal services centre: an application form, passports and birth certificates, certificates of family composition and certificates confirming that those who came to Russia previously lived in the Kherson region. If everything was in order, they could start looking for a flat to buy. Once they settled on an option, a preliminary sale and purchase agreement had to be drawn up. Then, all the documents along with the contract had to be again sent to the municipal services centre, where the decision on whether or not to issue a certificate would finally be made. At this stage, according to Kherson residents, the security forces would get involved. They scrutinised all the movements of the recipients of certificates and looked for any connections with Ukraine and Europe. If they didn’t like something, people were denied housing certificates without any explanation.

At the same time, some, on the contrary, received more money than they were entitled to:

“The system with certificates was very badly organised from the beginning, that’s why it was such a mess. I know families where 5-6 people were officially registered in one-bedroom apartments, but on paper, there was just one owner. In other cases, children and grown-up grandchildren were officially registered but didn’t live there. Some of them worked in Poland, the Czech Republic or other cities in Ukraine. And in the end, everyone got separate certificates. I also know a single father with a young child, who was registered in Mykolaiv, but paid cash for a house in Kherson in 2019. He provided all the required documents for the house but received nothing. His house was demolished after the [Kakhovskaya] hydroelectric power plant was bombed, and he has nowhere to live. So he ended up homeless with a child,” wrote one of the users in the refugee group chat.

“Nobody tells us what will happen next”

Before the war, 38-year-old Tatyana lived in a private house in the village of Brilyovka, about 50 kilometres east of Kherson. She was at home with her 13-year-old daughter when Russia invaded. At first, she said, everything was quiet, but when the fighting started near their town, it got “very loud”. Sometimes shells reached Brilyovka, and in August 2022, the Ukrainian army destroyed the railway station with rockets. Many houses in the village were destroyed.

“My daughter and I were in the basement for an hour and a half while the railway station was being bombed. We left the shelter at five in the morning, and that’s when I decided that we had to leave, because a child couldn’t stay there. My daughter was afraid to even sleep in the house. She went to school, but there was bombing and shelling around, so they told the classes would continue online. War is war, but a child must be educated. We decided to evacuate,” says Tatiana.

Like Alexei, Tatiana and her daughter went to Alyoshki. From there, a bus took them to the Krasnodar region and they were housed in the village of Lermontovo in the Tuapse district. Now Tatyana and her daughter live in the village of Dzhubga in a hotel where a temporary accommodation centre has been set up, with free rooms for refugees. At first, when they were living in the hotel in Lermontovo, they would get frequent visits from employees of various municipal services and local MPs, and their children were placed in schools. But then the help stopped.

“It’s been a year since we moved here and nobody has helped us with anything. I have to work because I have no other option, I have a child who needs clothes, food and an education. At school they also collect money from parents, as a holiday contribution”, Tatyana complains.

Over the past year, officials from the Tuapse district came by the hotel several times, but these visits were mere formalities. Tatyana and her daughter obtained Russian citizenship, and put together all the required documents, but received neither payouts nor a housing certificate. It turned out that the village of Brilyovka in the Kherson region, where she and her daughter had lived, was not on the list of eligible places, so its residents were not entitled to support according to the Russian government’s decree.

Tatyana tried reaching out to different authorities, called the Russian President’s hotline, contacted the administrations of Kuban and Crimea. But everywhere she’d get the same answer: it was the law and nothing could be done about it. Tatyana and her daughter are not alone: at the hotel, there are many people from Brilyovka and other villages that didn’t make the list, she says. None of them have any idea about where they will live in Russia

“What should we do? I have been living in temporary accommodation for two years. Nobody comes to see us, nobody cares. No one tells us anything about what will happen next. We can’t go on like this, we are afraid, we are worried,” Tatyana says.

Back in Brilyovka, her mother-in-law keeps telling her to come home, but Tatyana has no intention of going back because she doesn’t see a future for herself there. She took up a job as a cook in the hotel where they live. Her daughter goes to school, but she had to repeat a year: because of the war, she is falling behind the eighth-grade programme. Local officials keep promising to help the family and to convene a commission to solve all the issues, but it’s been a year and a half, and nothing has changed.

The Europe problem

According to members of refugee group chats, many of those who left Ukraine for Europe then went to Russia after learning about the possibility of receiving a housing certificate. At first, the authorities allowed this, but when the scheme became too popular, the rules changed.

Since August 2023, those who don’t come from Kherson to Russia directly (for example, through other European countries) can no longer buy housing using the certificate. It turned out that there are quite a few cases like that. As in the case of Alexei’s mother, not everyone was able to wait six months before Russian authorities started mass evacuation. Some left on their own at the beginning of the war, when the only way out of Kherson was to the west of the country, and then to Europe.

Some of these people, especially the elderly and families with children, moved to Russia after some time. As Kherson residents share in group chats, children were the main factor: they found it difficult to adapt in countries where foreign languages are spoken, especially after the horrors of the war. Others struggled to find a job without any language skills. And many had relatives in Russia.

From August 2023, during the so-called “filtering”, payments began to be denied to everyone who had been in Europe since February 2022, even if they were just passing through. Some people challenged these decisions in court: they managed to prove that they were transiting through European countries because it was impossible to get to Russia directly.

Judging by the stories that refugees shared in group chats, the case can be won if a person had spent no more than two or three days in Europe. If one stays there for a longer period of time, there is almost no chance of receiving payouts in Russia.

A user with the nickname “Lelya” wrote in the refugee group chat that her 85-year-old aunt fled from Kakhovka, when the shelling started there, to Italy, where her daughter lives. But the woman struggled to settle in: it was difficult without speaking the language and she was homesick. Three months later she returned to Kakhovka and from there went to Krasnodar, in Russia. There, she applied for a certificate, but her application was rejected because she had been in Europe. In the group chats, many were quite stern: since she didn’t go to Russia right away, she shouldn’t expect any payouts.

“Now she has to live under shelling, it’s mad. <…> Don’t put everyone in the same category, do you realise that the person in question is 85 years old? And she has only one daughter who lives in Italy, where else would she go? When the shelling calmed down a bit, she decided to come back. Yes, there are those who had received help in Europe, then they come here, buy a house, sell it, and leave, hating Russia. But this is a different category of people,” Lelya wrote.

Take a pick: going home or getting a certificate

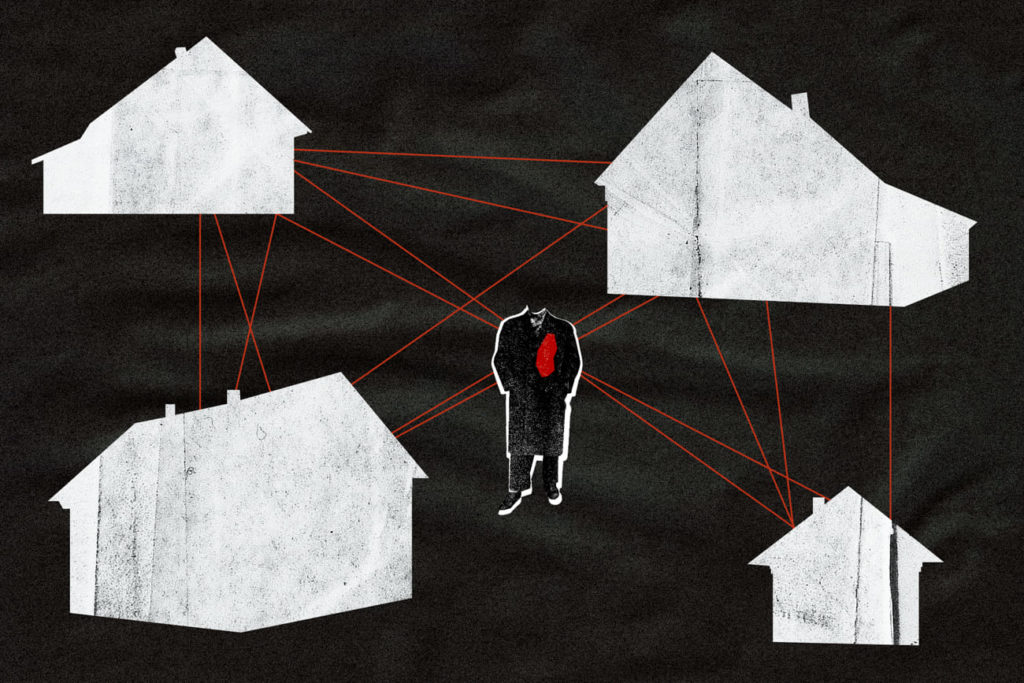

In the summer of 2023, after the rules for obtaining certificates and payouts were changed, members of the refugee group chatted about how many people buy flats and then sell them in order to return home with the money or leave for Europe or other Russian cities. In the Krasnodar region, a housing certificate for a family of three (approximately 4.8 million rubles) can only buy you a two-bedroom flat in an old building or a one-bedroom in a new building on the outskirts of the city. But for the same amount of money, you could get much more in other regions of the country.

Some Kherson residents in group chats look down at their compatriots who decided to “earn” extra money in Russia before settling in Europe. In their opinion, the rules for obtaining certificates were made stricter precisely because of those who were using those “loopholes”, but hit those refugees who actually want to stay in Russia and need housing.

It became difficult not only to go to Europe but to even go home to Kherson. According to locals, some people go there to get their belongings or documents. Some people try to get the best of both worlds: after buying a flat in Kuban, they rent it out and return home to Kherson.

Viktoria, a refugee from Kherson, said that in February 2024, together with her boyfriend, she obtained a certificate and was waiting to sign the purchase agreement for a flat in Krasnodar. After verification, a month later, the couple was denied the payment because they had crossed the border when they travelled to the Kherson region. Although they never tried to hide it: they personally made a request to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and attached documents when submitting the application. But their property agent is convinced that their request was denied because of that trip.

Victoria’s boyfriend travelled to the Kherson region to temporarily register there at his acquaintances’ house and to get on the military register. Now he has to go to back, as he received a summons from the local military commission which requires him to come in person. The agent warned the couple right away that in these cases, a man’s certificate is cancelled immediately.

Some people who left Kherson are annoyed: before the evacuation, Russian authorities promised to help all refugees, but the reality was different. Irina, a resident of the Kherson region, believes that if people had been warned about the conditions for obtaining certificates right away, many wouldn’t have agreed to evacuate:

“I had been in Kherson since 2012, got married in Kherson, and lived since 2017 in my husband’s flat, where our child is registered. I didn’t even bother about my official registration. Here, I struggled with getting a certificate for a year. In the end, I got it, but then something went wrong. My question is: why the hell did they write “to citizens who were forced to leave Kherson” if, since the beginning, the most important thing is the official registration”, – Irina wrote in the group chat.

“We are second-class citizens here”

In the autumn of 2022, when Aleksei was evacuated from Kherson and ended up in Anapa, he was housed in a hotel with, as he himself describes it, “excellent conditions”. He lived there until the start of the holiday season. Then, all refugees were taken to other, less popular among tourists, cities. Alexei ended up in the Dinskaya district near Krasnodar, where, he recalls, “it all went to shit”.

In Anapa, he managed to get a Russian passport, but he still doesn’t have a local official registration. The bus that was supposed to take some people to the new temporary accommodation centre in the Dinsky district simply did not arrive at the appointed time. The refugees were told that there were no more seats on the buses and that they would have to travel the next 300 kilometres on their own. Alexei eventually had to leave Dinsky district: there was no work for him in the village where the temporary accommodation centre was located.

“A lot of time has passed since then, and I am still homeless without an official registration or a permanent residence. No matter who I turn to, no one gives a shit,” Alexei says.

Although Alexei lived in Kherson, he was officially registered in the Mykolaiv region, where his other grandmother lived. Because he sometimes has seizures, for a while, he has been registered in a psychiatric hospital. His mother, who is now in Germany, looked after him at home.

In order to receive a housing certificate and a payout, Alexei reached out to various authorities, but to no avail. Then he moved to Krasnodar, got a job at a local delivery service “Yandex.Dostavka” and took out a loan to rent a place to live and buy the bare necessities. Thanks to the help of some locals, he was able to rent a room in a hostel, and he invests part of his earnings “for retirement”.

“My story is news for those who follow the rules and have no clue about how to deal with those that go against them [meaning state bodies responsible for payments — Editor’s note],” Alexey says, surprised with how the refugees’ arrival has been organised.

Tatiana continues to live and work as a cook in a hotel on the Black Sea coast. She is one of the 44 refugees that remain there. She still hopes that she and her daughter will get help and won’t be forgotten. The family lives in constant fear, afraid that the Russian government will finally shut down all support programmes and abandon them.

“Who gives a damn? The hotel owners don’t care, they will immediately kick us out and that’s it. We are already tired. It’s hard, we live in temporary accommodations, it’s hard, there’s no point. No plans for the future. You had a life, you had a job, everything was stable, you lived at home, you knew how everything worked, and now we are second-class citizens here,” Tatiana concludes, disappointed.