Now that Russia has marked the 80th anniversary of its victory in the “Great Patriotic War,” the state’s reinterpretation of wartime history has only intensified. Courts across the country continue to classify select WWII events as acts of genocide against the Soviet people. In Karelia, the Finnish occupation has become one such case — the 22nd genocide ruling issued by regional courts since 2019.

In this investigation for The New Tab, journalist Lola Romanova explores why authorities are revisiting events from eight decades ago, why official discourse largely avoids discussing the experiences of Karelia’s Indigenous population under Finnish control, and whether the genocide verdict has brought any tangible change to the lives of former prisoners of Finnish camps.

The original piece was published in February 2025.

On August 1, 2024, Karelian journalist Valery Potashov left his house in Petrozavodsk. He was planning to attend the final court hearing on the recognition of the actions of the Finnish occupation army as genocide against the Soviet people. But on the street, he was arrested by the FSB. They were raiding the apartment while explaining to the journalist that he was being checked for possible participation in the activities of an “undesirable organization.” Due to the siloviki’s visit, Valery Potashov was unable to attend the court. “It feels like they were just keeping me in the apartment”, Potashov suggests.

On the day of the first court hearing, 19th of July 2024, the Karelian FSB threatened journalists with criminal charges for treason if they produced “anti-Russian content” while covering the trial.

“They did not receive the punishment they deserved.”

Dmitry Kharchenko, acting on behalf of Russian Prosecutor General Igor Krasnov, was the one who in June 2024 submitted a statement to the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia requesting that the genocide of the Soviet people during the Finnish occupation be recognized as such. The Prosecutor General’s Office informed that this was being done, among other things, to “restore historical justice.” Materials from a separate criminal case under the Russian Criminal Code, specifically the article on “Genocide,” were included in this lawsuit. The case, initiated in 2020 by the Investigative Committee of Russia, concerns the actions of the Finnish occupation army.

Criminal cases concerning the genocide of the USSR’s civilian population during WWII began being filed as early as 2019. At that time, the first such case was reported in the village of Zhestyanaya Gorka in the Novgorod Region. The grounds for this were the 1942-43 mass graves discovered by participants of the “Without Statute of Limitations” (“Bez sroka davnosty”) project, which was launched in 2018 by the Search Movement of Russia, whose leadership includes State Duma deputy Elena Tsunaeva from the ruling “United Russia” (“Yedinaya Rossiya”) party. The declared aim of the initiative is to preserve the memory of “the victims of Nazi war crimes and their collaborators during the Great Patriotic War.”

In 2020, the Soletsky District Court in Russia’s Novgorod region ruled that the actions of Nazi forces in the village of Zhestyanaya Gorka constituted genocide against Soviet citizens, citing UN General Assembly resolutions and the Nuremberg Tribunal’s charter. It was the first decision of its kind in Russia — and it set a precedent. In the years that followed, courts across both Russia and Russian-occupied territories issued similar rulings, declaring various wartime atrocities to be acts of genocide.

“Following the geopolitical interests of the Soviet Union and, at that time, Great Britain, Finnish war criminals did not receive the punishment they deserved. Only Finland’s political leadership, in other words, the president and some ministers, were convicted. However, none of them spent more than three or four years in prison,” said Denis Popov, a master’s student at Petrozavodsk State University, as a witness for the prosecution at one of the court hearings. “During the Soviet era, we maintained warm relations with Finland, characterized by economic, political, and cultural cooperation. Consequently, mentioning the Finnish invasion of Karelia was uncommon.”

Invasion and Reconstruction

The concept of Greater Finland was a guiding principle for the Finnish invasion army during WWII. Zheny Parfenov, a postgraduate student in the Department of National History at Petrozavodsk National University and a staff member at the National Museum of the Republic of Karelia, specializes in regional war history and the partisan movement of the 1940s. He explains that the idea of Greater Finland began to emerge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, influenced by several factors, including the forced Russification policies implemented by Alexander III and Nicholas II in Finland. Dissatisfied with the actions of the Russian emperors, many Finnish activists sought refuge in Germany.

In 1918, after the Finnish Civil War, anti-communist sentiments among Finns shifted to anti-Russian feelings. This change led society to consider the possibility of incorporating Russian territories that were home to Finno-Ugric peoples. The Winter War (Talvisota) of 1939-1940 further complicated the relationship between the Soviet Union and Finland. As a result of this conflict, Finland lost a significant portion of its territory and forged a bond with Germany, becoming, if not officially, then effectively an ally of the Third Reich in the ongoing war against the USSR.

The Soviet-Finnish War began on November 30, 1939 with a Soviet invasion of Finland, three months after the outbreak of World War II, and ended on March 13, 1940.

Due to their ethnic affinity with the Finns, even before the war, the Karelians were subject to reprisals in the USSR. Throughout 1937-1938, during Stalin’s reign and the Great Purge, “national operations” took place in Karelia: arrests “along the Finnish line” also affected the Karelians. In 1937, the Vepsians, or Veps, were also subjected to prosecution: the battle between the Soviet leadership and national distinctiveness resulted in the shutdown of Vepsian schools, the cessation of teaching in the Veps language, and the repression of the national intelligentsia.

In 1941, when the Finnish troops invaded the territory of Karelia, they divided the people into “national” (the Veps and Karelians) and “non-national” (the Russians). According to the Finnish idea, the Veps and Karelians would be part of a future Greater Finland. With the arrival of the Finns, there were no significant changes in the countryside with a “national population”, says the historian Alexei Golubev. “Just as they lived in Spartan conditions [after collectivisation], [but] did not die of hunger, so they continued to live under the Finns.”

Alexei Golubev is a Doctor of Philosophy at the University of British Columbia, Associate Professor of Russian History at the University of Houston, and one of the compilers of the Petrozavodsk State University collection of academic articles, «Устная история Карелии» (The Oral History of Karelia, 2007), which reflects the historical experience of different nationalities in Karelia during the Great Patriotic War.

“Non-national” population was placed in labor and concentration camps, with plans to send these people to German-occupied territories in the future. Food in the camps was extremely scarce, and the prisoners were subjected to corporal punishment. They were required to work, most often logging. They were paid a salary, but it was meager.

The number of prisoners changed over the years. In May 1942, there were nearly 24,000 people in Finnish concentration camps in Karelia, and at the beginning of 1944, according to researchers’ estimates, there were about 15,000. The total population of Karelia at that time was just over 83,000. It is impossible to say how many people died of starvation and unsanitary conditions in the six concentration camps in occupied Petrozavodsk alone: statistics vary from 7,000 to 14,000 people. Some of the “non-national” population lived freely, but only because there was simply no time to send them to concentration camps, notes Alexei Golubev.

In 2020, the charity foundation “Open Opportunities” in Karelia attempted to recreate the everyday life of the Finnish occupation period and built a mock concentration camp at a private recreation center in the village of Vatnavolok. The barracks and guard towers were donated to the foundation after the filming of the feature film “Vesuri,” which tells the story of young prisoners in camps. An exhibition with photographs and everyday utensils was set up in the camp with plans to hold patriotic excursions for schoolchildren there. The Presidential Grants Fund allocated almost 3 million roubles for the project. But the fake concentration camp did not have time to function: it closed just a couple of months later (allegedly due to COVID-19 restrictions). It is now abandoned.

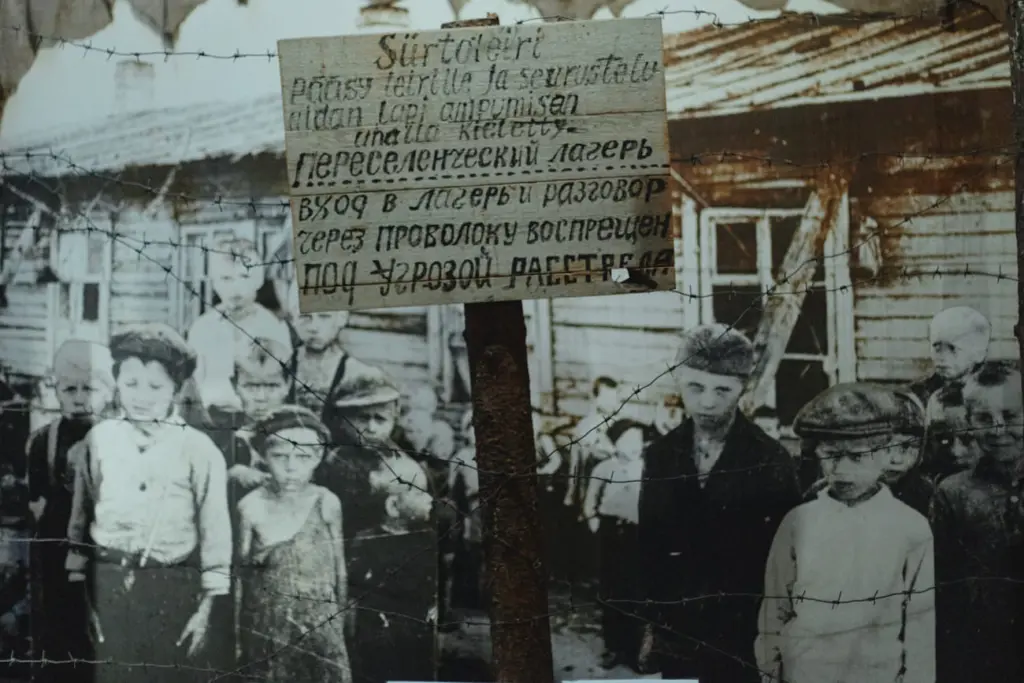

Since 1986, Lyceum No. 13 in Petrozavodsk has been home to the “Children of War” school museum, which is dedicated to the occupation of Karelia. A large portion of one wall features a documentary photograph of freed child prisoners from a Finnish concentration camp, captured by war correspondent Galina Sanko. Near the ceiling, the walls are adorned with barbed wire and Soviet propaganda posters from WWII. One of these posters, created by the Kukryniksy, proclaims, “We will mercilessly crush and destroy the enemy!”

Soviet graphic artists and painters — Mikhail Kupriyanov, Porfiry Krylov and Nikolai Sokolov. They are known for their political cartoons and posters.

“A diverse group of people has inhabited the territory of the Republic of Karelia and continues to live here today. If we were to single out specific groups, it would be unjust,” a lyceum employee explains to museum visitors why the exhibition focuses exclusively on the experiences of the Russian population during the war, rather than including the experiences of the Veps and Karelians. After the Finnish army’s actions were acknowledged as genocide against the Soviet people, nothing changed in the museum; this fact simply began to be mentioned during tours.

Genocide as a Weapon of Political War

According to Valery Potashov, the summer court hearings represent a “logical continuation” of the recent excavations at Sandarmokhv. These excavations were initiated in 2019 by the Russian Military Historical Society, in collaboration with the regional branch of the Russian Search Movement. Their goal was to locate the graves of prisoners from Finnish concentration camps and fallen Red Army soldiers. At that time, members of the Memorial Historical Society raised concerns that Cossacks were involved in the excavations instead of qualified archaeologists. Although researchers did not find any evidence of victims of the Finnish occupation buried at Sandarmokh, a memorial plaque acknowledging this was still erected at the site.

A forest area in Karelia where mass shootings and burials of Soviet citizens occurred during Stalin’s Great Terror. This site was discovered and initially researched by the Karelian historian Yuri Dmitriev from Memorial.

In total, six hearings were held in the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia during the summer of 2024 regarding the recognition of the actions of the Finnish army as aggressive against the Soviet people. The speakers were primarily historians from Petrozavodsk and Moscow, and there were no researchers present who could represent the Finnish perspective. Karelian journalist Valery Potashov noted that the trial was conducted in an “accusatory manner” and was largely “political.”

In addition to historians, “interested parties,” as they were termed during the hearing, also spoke in court. This included former child prisoners of concentration camps and the head of the Republic of Karelia, Artur Parfenchikov.

Historian Zheny Parfenov, who appeared in court as a witness, commented, “It is difficult to hold a court hearing 80 years later. The real witnesses available are elderly individuals who were in Finnish concentration camps as children. They have their own perspective on that period; they do not possess the full picture of what transpired and only recall specific facts from their experiences.” He also discussed Finland’s opposition to partisan raids and underground activities in the occupied part of Karelia.

On August 1, 2024, the Supreme Court of Karelia recognized the actions of the Finnish army in the region during the “Great Patriotic War” as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. The court’s decision, similar to the ruling in the case of Zhestyanaya Gorka, refers to the resolutions of the UN General Assembly and the Statute of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal.

The 1946 UN General Assembly Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide defines genocide as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.” In the Karelian prosecutor’s statement of claim, the cruelty of the Finnish regime is described as creating “conditions incompatible with life,” a clause included in the Convention.

Accusations of genocide have become increasingly common at the international level in recent years, particularly in relation to Israel’s military actions in the Gaza Strip and Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

“The concept of genocide is shifting from a legal context to a political one, making the historical background of the Karelian Supreme Court’s decision more understandable,” explains historian Alexei Golubev. “If Russia’s actions in Ukraine are recognized at the public level within the European political arena as …, we are no longer discussing … in legal terms. Instead, … becomes a tool of political struggle. It’s akin to the saying: if you call your friend stupid, she will likely respond in kind — that is roughly the level of discourse we’re seeing.”

Zheny Parfenov believes that the Karelian Supreme Court’s decision is primarily a ‘symbolic act of historical justice’ that former child prisoners of concentration camps, along with historians and politicians, need. Making material claims against Finland is particularly challenging after the 1947 Paris Peace Treaties, which outlined the reparations that the Soviet Union would receive from Finland. These reparations were fully paid by 1952.

“A Dress to Bury Verushka In”

“You’re talking about the recognition of genocide, but I’m not familiar with it. Can you tell me what happened?” asks Marina Smirnova, the daughter of 87-year-old Vera Khamelova, a former child prisoner in a concentration camp in Karelia. She learned about the court hearings from me and mentions that nothing has changed in their lives.

For the past three years, mother and daughter have been living together in Petrozavodsk. Vera Nikolaevna has poor hearing, so Marina Ivanovna often answers questions on her behalf. As a child, she frequently heard stories about the concentration camp from her grandmother, making the war a shared memory for them. This upsets Vera Nikolaevna; she wants to share her childhood experiences herself.

At the beginning of the war, her family lived in Sennaya Guba, a village in the Medvezhyegorsk district. They remained there until the winter of 1941, and in February, four-year-old Vera, her pregnant mother, grandmothers and sister were transported by truck across the frozen Onega River to Petrozavodsk and placed in concentration camp No. 4. The winter, Vera Nikolaevna recalls, was harsh. Her maternal grandmother was wealthy and was able to carry gold with her in a bag around her neck: it was exchanged for food in the camp. This saved their lives.

There was still not enough food, and the girl fell ill with edema while in the camp. “My stomach swelled up, and I lay on a mattress on the floor. My grandmother thought I was going to die, so she washed a dress to bury Verushka,” recalls the elderly woman. The girl recovered thanks to a paramedic who worked at the camp hospital.

After the war, Vera Khamelova’s family moved to Velikaya Guba, where she started school at the age of seven. However, her time there was short:

“The teacher showed us a picture and asked who was depicted in it. The picture featured chickens, but I had never seen any in the camp. There were chickens running around in the yard, though. So, when I answered “Kurichi” instead of “Kuritsi” (my grandmother used to say ‘ch’ instead of ‘ts’), the other children burst out laughing. I felt upset and told my mother that I wouldn’t go to school anymore.”

Vera returned to school a year later, went on to university, and eventually taught English and German at a school affiliated with a factory in Kondopoga. Her former colleagues congratulate her every year on May 9th. On her table, next to a tiny bear figurine that Vera Nikolaevna brought back from the German Democratic Republic during the Soviet era, sits a postcard commemorating the 75th anniversary of Victory Day. There are also magazines from the school library that her daughter brings to her. Vera Khameleva often reads memoirs about the Finnish occupation and various historical notes, though she admits her nose is sore from wearing glasses.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the German Foundation for Mutual Understanding and Reconciliation provided monetary compensation to Vera Nikolaevna as a former concentration camp prisoner. This foundation was established in 1993 at the initiative of the German government to offer payments and charitable assistance to victims of Nazism. However, in 2011, the Russian government closed the foundation, believing it had fulfilled its objectives. The German side argued that this decision deprived several thousand former prisoners of war and concentration camp survivors of the opportunity to receive compensation. In December 2024, during a meeting of the Budget and Tax Committee of the Karelian Legislative Assembly, deputies did not support a proposal to provide the “children of war” living in the republic with at least a thousand rubles in recognition of the 80th anniversary of Victory Day.

Marina Ivanovna expressed that they are not actively seeking help; they are content with the fact that her mother can access disability benefits and receive free medication.

“The Campers are Coming”

Lenina Makeeva, an 89-year-old former child prisoner of a Finnish concentration camp from Petrozavodsk, has no relatives and requires assistance with shopping and cleaning. Due to cancer, she cannot lift heavy objects.

“I take 250 grams of bread, which is about half a loaf, and one or two potatoes,” the pensioner explains about her trips to the store. “Once, I filled my trolley with sugar, left the store, and looked around to see if anyone was walking by with their hands free. I ask them to help me take my trolley to the crossroads, and they kindly do. Then I look for the next person who could assist me.”

Lenina Makeeva believes that the case of genocide was brought “for show,” but she hopes it will help draw attention to an issue she has been advocating for over the past two years: securing free social services for former concentration camp prisoners. Unfortunately, Makeeva cannot receive such support because her pension of 50,000 roubles exceeds the subsistence minimum, making her ineligible for social services designed for former juvenile concentration camp prisoners.

In the summer, Lenina Pavlovna appeared in court to support the prosecutor’s statement that the actions of the Finnish army were genocide against the Soviet people. She was sent to concentration camp No. 5 in Karelia at the age of five. During her time there, two of her sisters and her grandmother died of starvation, and her mother fell seriously ill. After her release, Makeeva recalls, life remained challenging. Former prisoners often faced ridicule, being shouted at with phrases like, “The campers are coming!” Due to her childhood experience in a concentration camp, Makeeva was not accepted into the Komsomol and later was unable to enroll in a full-time university program, forcing her to study part-time.

When Lena Makeeva eventually found a job, she was required to present a certificate from the KGB each year, confirming that she had not committed “illegal actions against the people.” She started her career as a ticket clerk on the railway and later worked in the tax office.

Lenina Pavlovna currently leads the Karelian Union of Former Child Prisoners of Nazi Concentration Camps, which was established in 1989 to provide mutual assistance and educational support. Initially, 1,490 people expressed interest in joining the union. According to Makeeva, the union now has 86 former child prisoners as members. Lenina Pavlovna shares that her work with the union keeps her engaged and helps her avoid boredom. During our conversation, she changes her clothes several times to display her various medals, including those for being a war veteran, a concentration camp prisoner, and awards from the Ministry of Finance.

“I am persistent by nature,” Lenina Pavlovna says proudly. This is not her first battle for her rights. In 2005, the Russian government started offering payments to former concentration camp prisoners: 1,000 rubles per month for former juvenile prisoners and 500 rubles for adults. However, Makeeva’s mother was denied this supplement because the Pension Fund claimed that Finnish concentration camps were not considered Nazi camps. Lenina Pavlovna fought for two years to secure an additional 500 rubles for her mother’s pension, and the payment was only granted after a court ruling.

This is approximately eight times less than the average salary in Russia at that time (in June 2005, it was 8,655 rubles).

In October 2024, Lenina Makeeva sought assistance from the prosecutor’s office to obtain free social services. However, the Petrozavodsk prosecutor subsequently filed a lawsuit against Makeeva, demanding that she pay 30,000 rubles in moral damages due to her repeated attempts to receive help. The Petrozavodsk City Court held the hearing on January 29, 2025, where Judge Lyubov Davidenkova denied the prosecutor’s claim.

“Advocate for Finnish Life”

During WWII, the Karelians and Veps living in Finnish-occupied territories were sent to concentration camps significantly less often than the Russian population. Ekaterina Ponomareva (This person asked to change her name and not to mention the village.), a 57-year-old resident of one of the national villages, has learned about this history from archival documents and family stories. She is hesitant to discuss the war period, fearing that following the court’s decision to recognize the actions of the Finns as genocide, people in Russia may interpret certain events differently.

The village where she resides historically belonged to the Karelians, and the Finns regarded them as a brotherly people. During the occupation, collective farmland was transferred to local residents for private use, and horses were provided. Children attended school and helped out in the fields.

Among the things the Finns did during the occupation, Ponomareva mentions the Orthodox chapel. Before the war, it was partially destroyed, and the Finns allowed the local residents to restore it. “If they hadn’t done so, no one would have allowed the building to be repaired during the Soviet era, and the chapel would not have survived to this day,” the woman sums up. The villagers had the opportunity to visit the chapel, where a Finnish priest served as what Ponomareva describes as “an advocate for Finnish life.” According to her, he even conducted a service according to Orthodox traditions at least once. After the war, however, the chapel was closed.

During the war, Ponomareva’s aunt was taken to Finland for work. Her family had no idea where she was, as she did not write to them out of fear of being deported from Finland and subsequently exiled to Siberia. Twenty years later, she finally sent a letter to her family, informing them that she had married a Finnish officer and had children.

After the war, there were no mass resettlements of Karelians, but Ponomareva’s parents recalled that life remained difficult for them. “Karelians were not considered human beings in the USSR. My father never admitted to knowing Karelian, whether in the army or at work.”

“When my relative went to school in the 1970s, she spoke only Karelian. Children were forbidden to speak it, even during breaks, and they were often punished for doing so. ‘Speak Russian,’ they were told,” recalls Ekaterina Ponomareva, acknowledging that years of national policy have created complexes among the Karelians. “We are afraid to say that we are Karelians.”

Historian Alexei Golubev observes that the silence surrounding the experiences of the ‘national’ population during the Finnish occupation is not coincidental. He states, “The experience of collaboration is discredited by all societies that have undergone it. Any nation that liberates territories after a long occupation is not interested in an objective study of the historical experiences that occurred in these occupied areas.”

After the war, the USSR began to collaborate with Finland. Notably, Soviet and Finnish builders jointly constructed a large mining and processing plant in the northern Karelian border region, marking the beginning of the city of Kostomuksha. According to journalist Valery Potashov, one of the greatest accomplishments of Russia and Karelia following WWII was the establishment of friendly relations with the Finns. He highlights that the main issue with the genocide cases is the deterioration of these relations:

“A few years ago, I spoke with veterans of the Winter War, and they shared how they met with our veterans, drank together, and reminisced about those times. Unfortunately, today we have reverted to viewing the Finns as enemies.”