In January 2025, Elena Khlomko of Petrozavodsk followed her doctor’s advice and admitted her 29-year-old son, Ivan, who has a rare genetic disorder, to the Republican Psychiatric Hospital. Just five days later, he was in intensive care with sepsis and kidney failure — and his leg had to be amputated. At the clinic where he was transferred, doctors suggested the injuries may have resulted from prolonged compression. After the story ran in Karelian media, hospital staff refused to speak with Elena. But patients themselves came forward to The New Tab, describing a system where people are tied to beds with belt loops from their gowns, locked in wards without toilets, and forced to mop floors or empty bedpans in place of orderlies.

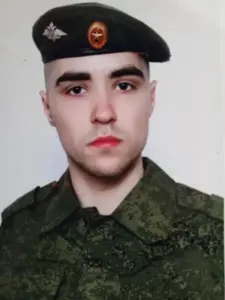

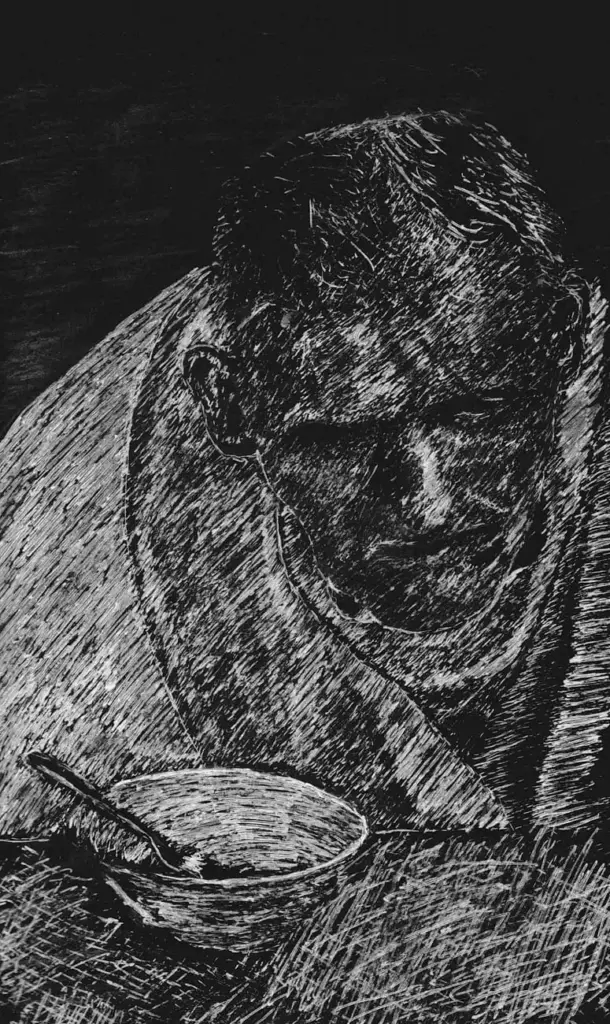

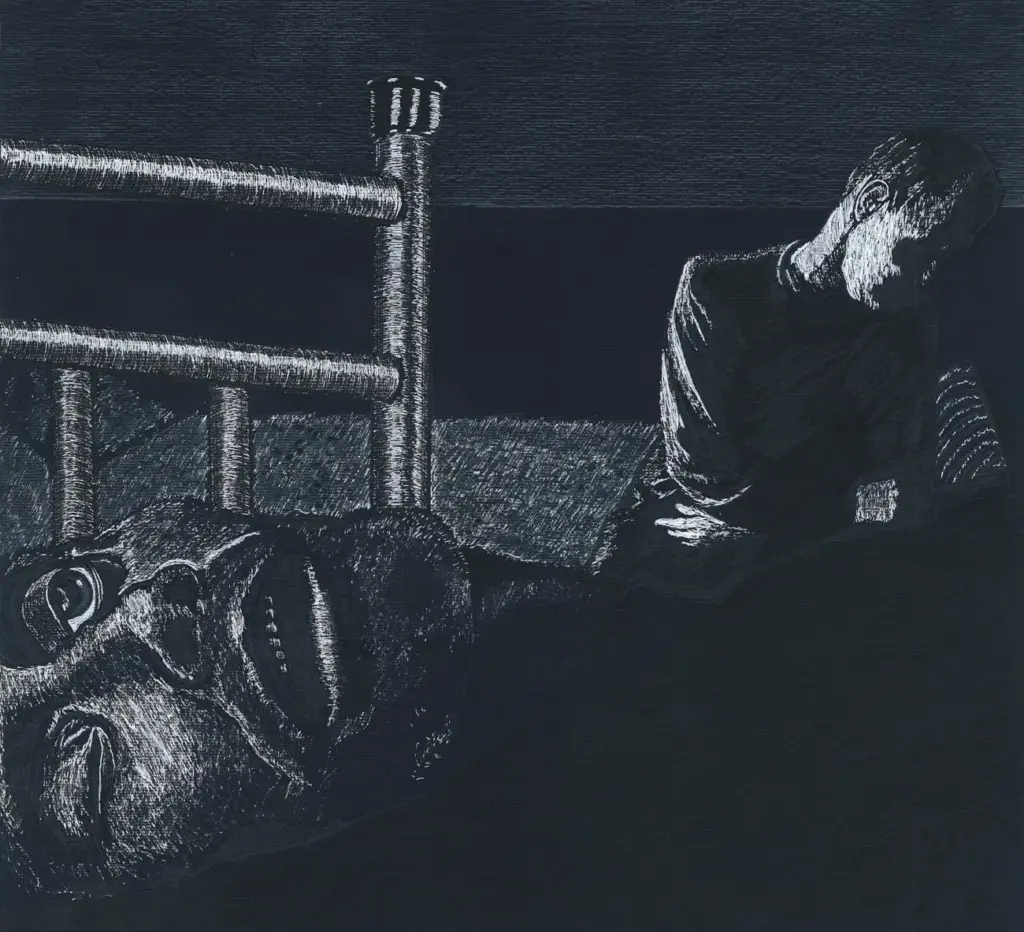

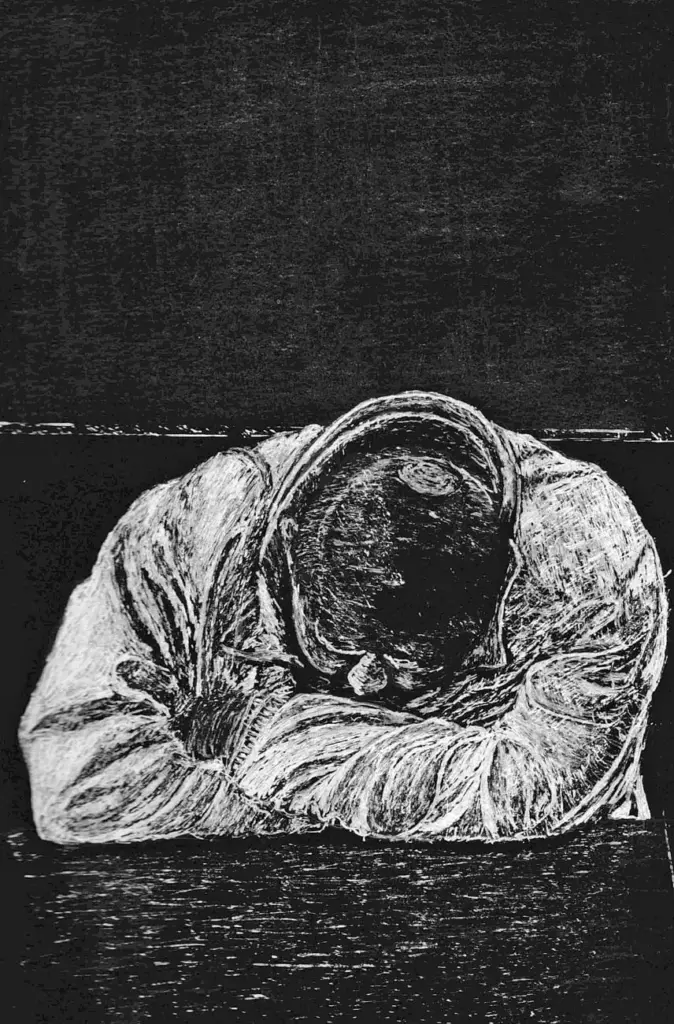

The illustrations accompanying this report were created by an artist who was personally examined at the hospital by doctors.

The original piece was published in April 2025.

“They Brought a Living Corpse”

When Ivan Khlomko was 19 years old and serving in the army, his parents began to notice that his speech was becoming slurred during their phone conversations. Initially, they attributed this to poor reception. However, upon Ivan’s return home, other concerning issues surfaced, including difficulty with coordination. The disease progressed slowly, leaving Elena and Valery Khlomko confused about what was happening to their son. They consulted various specialists, but it wasn’t until Ivan turned 24 that he was diagnosed with the rare Huntington’s disease. Gradually, he began to lose basic functions, such as using the toilet, speaking, and eating. Now, at 29, his condition has worsened.

Huntington’s disease is a hereditary, slowly progressive disorder of the nervous system that causes involuntary movements, known as chorea, which cannot be suppressed and may spread from one part of the body to another. The disease is also associated with mental disorders.

Huntington’s disease is a hereditary, progressive disorder of the nervous system that leads to involuntary movements, known as chorea, which can shift from one body part to another and cannot be suppressed. This disease is also associated with mental disorders.

In early 2025, Ivan’s parents contacted psychiatrist Evgenia Morozova, who was treating him at a psychoneurological clinic. They were concerned about his deteriorating condition, as he had practically stopped sleeping. Additionally, they sought a medical opinion to have their son declared legally incompetent, which would allow them to apply for a pension on his behalf. To obtain this evaluation, the doctor referred Ivan to the Republican Psychiatric Hospital (RPH) in the village of Matrosy, near Petrozavodsk.

In Karelia, the psychiatric clinic is commonly known as “Matrosy”, named after the village. It is the only facility in the republic that offers inpatient psychiatric care. Irina Glatenok has served as the chief physician at the RPH since 2010.

On Wednesday, January 22, 2025, two paramedics arrived to take Ivan to Matrosy Hospital. Elena expressed that arranging this was challenging, as her son rarely left the house and was resistant to going anywhere with strangers. However, ultimately, the two strong men were able to assist him. The hospital assured Elena that Ivan would only receive the medications he was already taking. He was to be monitored by psychiatrist Anton Shevtsov and the junior medical staff. Once a day, his parents planned to call the sixth ward to check on their son’s condition.

On Saturday, after speaking with a nurse, Elena Khlomko became alarmed. “The woman barked into the phone and said that Vanya was sleeping all the time. But he never sleeps,” she explained.

Elena reached out to a friend who works at the RPH and received a concerning message: “Lenchik, what is happening is completely inadequate. Yesterday, during my shift, a girl visited the ward to inquire about Vanya’s condition. They yelled at her and told her to get out and go back to her ward to check there. Consult a doctor about the patient’s condition.” After that, the friend did not respond to Elena’s messages.

On Sunday, Dr. Shevtsov told the Khlomkos that their son had a fever and was given ibuprofen. However, on Monday, January 27, Ivan was first admitted to the city’s emergency hospital and then to the Republican Infectious Diseases Hospital. For several days, Elena was unable to find out where he was. With the help of friends, she eventually located him: Ivan was in a coma in the intensive care unit of the Baranov Republican Hospital, where he had been transferred from the infectious diseases hospital on January 30.

An infectious disease specialist from the Republican Infectious Diseases Hospital later told Elena over the phone that they had been “brought a living corpse.” Ivan had a high fever, blackened, icy feet and hands, kidney failure, and sepsis. A gastroenterologist at the Baranov Republican Hospital later explained to Elena that Ivan may have developed crush syndrome. She suggested that his arms and legs had been tied to the bed for a prolonged period, which caused tissue necrosis; once the restraints were removed, toxins could have entered his bloodstream, triggering sepsis and kidney failure.

Crush syndrome, also known as prolonged compression syndrome, occurs when the blood supply to soft tissues is cut off for an extended time. Along with local symptoms such as swelling and pale skin, it can lead to severe systemic complications, including kidney failure.

Ivan’s left leg had to be amputated. Elena was allowed to see him both before and after the operation. She noticed strange black marks on his feet and knees — and took photographs of them.

According to Khlomko, her son had no heart, kidney, or vascular problems before his stay at the Republican Psychiatric Hospital; all of these complications developed afterwards. The hospital refused to provide the parents with access to the security camera footage.

The Khlomkos turned to local media for help, but after Daily Karelia published their story, the doctors stopped speaking with Elena and no longer mentioned the possibility of crush syndrome.

That same day, the Karelian Ministry of Health announced on its VKontakte page that an investigation was underway. Even before the results were available, officials insisted that “prolonged compression measures” had not been used on Ivan and claimed that his leg was amputated due to a blood clot. The statement, however, did not explain why Ivan had to be transferred first to the emergency hospital and then to the infectious diseases hospital following his stay in the psychiatric hospital. The Ministry also confirmed that the duty doctor and staff at the contagious diseases hospital had not provided any information to the patient’s family.

Since Ivan Khlomko is still in intensive care at the Baranov Republican Hospital, his relatives do not have any medical documents describing his diagnosis and the course of his illness.

“I Saw Them Tie Him Up”

But Ivan Khlomko’s case encouraged some patients at the Republican Psychiatric Hospital to speak out. Not all, of course — most refused to talk to journalists, fearing they might be forcibly hospitalised again. Still, a few agreed to share their stories with the New Tab, even claiming they had seen Ivan tied up and left “for five days in the January draft” in the corridor of the hospital’s sixth ward, directly beneath a .surveillance camera.

“They tied him [to the bed] by his hands, that’s certain. I even saw him, still restrained, roll over and break his arms. He’s a physically strong man,” recalls Andrei Kuznetsov (The name has been changed) from Petrozavodsk.

Andrei, who lives with a mental disorder he asked not to be named in the publication, first developed symptoms later in life, at the age of 30. The diagnosis does not prevent him from leading a normal daily life, but once every two or three years, his condition worsens, and he is admitted to the RPH. The acute phase lasts 8–10 days, but he is typically kept for another 20–30 days until his state stabilises. Kuznetsov was being treated in the hospital’s sixth ward at the same time as Ivan Khlomko in January 2025.

Kuznetsov is outraged that doctors informed Vanya’s parents that they did not administer any additional medication to their son. He believes this statement is a lie: “Everyone who enters Ward Six is given a mysterious injection, after which patients sleep excessively.” He adds that patients are filled with so many drugs that they can barely make it to the toilet, constantly in a daze and on the verge of fainting.

“Complete Hazing”

Andrei Kuznetsov agreed to speak only on condition of anonymity. Like other patients, he is registered at the Republican Psychiatric Hospital and fears being “forcibly hospitalised.” He had long wanted to talk about conditions in the sixth ward, and after the incident with Ivan Khlomko, he finally decided to do so.

Over the course of our ninety-minute conversation, we discussed many issues — from the harsh use of restraints to the dilapidated state of the hospital. The RPH building has not undergone renovation since it was opened in 1985. “Walls painted with oil paint, like in a stairwell, and heavy metal beds — that’s the sixth ward,” Andrei says.

When a patient is admitted, all personal belongings are taken away, including jewellery. “They change you into second-hand rags, and you become faceless — just another psycho,” Kuznetsov recalls.

According to him, there is no toilet paper in the bathrooms. For a “first-time intelligent newcomer,” he says, “you don’t yet know how to wipe your bum with your hand — and that becomes a problem.” He is also outraged by the practice of shaving patients with a shared disposable razor. Two long-term patients in the ward are assigned to shave bedridden patients: “If you accidentally cut one, you just rinse the razor under water and move on to the next.” Kuznetsov warns that this practice carries a serious risk of bloodborne infection.

According to Andrei, the department employs two doctors, but they only make morning rounds on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. He notes that the doctors are generally polite to patients, but treatment consists solely of medication. There are no individual sessions with a psychologist, no group activities, and certainly no discussion groups or “fairy-tale therapy,” as advertised on the hospital’s website. Patients only meet with a psychologist upon discharge. Although there is a rehabilitation room where patients can read or draw, Andrei insists that no one ever uses it.

By contrast, junior medical staff, Andrei says, treat patients “like second-class citizens,” despite having the most direct contact with them. Nurses and orderlies, he claims, communicate “exclusively with foul language and raised voices, often resorting to personal insults.” Orderlies even refer to the wards as “cells” and compel patients to clean them in exchange for “the cheapest cigarettes.”

“Patients scrub floors, empty bedpans, help others to urinate, and change diapers. Patients do everything. The orderlies call it ‘work therapy,’” Kuznetsov explains.

Another RPH patient, 39-year-old Evgeny Stepanchuk, confirms the existence of “work therapy” in exchange for cigarettes. Officially diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder, he believes — based on consultations with other doctors — that he actually suffers from depression. Evgeny was first admitted to Matrosy in 2018, in the ninth ward, but has also spent time in the sixth. He describes the conditions there as “complete hazing.”

Bipolar affective disorder (BAD) is a mental illness characterised by periodic episodes of elevated mood (mania or hypomania) and episodes of depression, which may alternate with each other. The global population of people living with bipolar affective disorder is estimated at 40 million.

The ninth ward houses patients with milder diagnoses than those in the sixth, mainly neuroses and depression.

According to Andrei Kuznetsov, staff refer to the patients who clean wards and perform other menial tasks for the orderlies as “workers.” In addition to cigarettes, these “workers” receive extra food at lunch or dinner — at the expense of the rations for other patients.

“The workers get more food, while we’re left without enough tea or bread. And every time you see it, you think: ‘God, what have I done wrong to deserve less?’” Andrei says.

Patients without relatives who can bring them food parcels are especially vulnerable. Even those with family in Petrozavodsk often struggle, as the hospital is 40 kilometres away and frequent visits are difficult. Kuznetsov recalls going to bed constantly hungry — even smuggling bread out of the dining room “in his underpants,” though, he admits, he never eats bread at home.

Those unable to feed themselves — as in Ivan’s case — must rely on the help of fellow patients. Andrei describes how he and his roommates fed bedridden patients and monitored IV drips, effectively doing the work of both orderlies and nurses.

Psychiatrist Maxim Novikov (The name has been changed), who previously worked at the Republican Psychiatric Hospital, confirms these accounts and stresses that human dignity is often shaped by the smallest aspects of daily hospital life: “You can feel humiliated not because an orderly beats you, but because you’re only allowed to shower once a week.” He recalls how, during his time at the hospital, the issue of purchasing sanitary pads for the women’s ward arose — the staff had to collect donations through social media appeals.

“The Body Turns to Stone”

The conditions in the sixth ward could almost be considered torture on their own, but the patients’ suffering doesn’t stop there. Restraints, or “ties” as they are commonly referred to in the hospital, are a standard practice in the ward. While professional restraint devices exist, in the sixth ward, Andrei Kuznetsov says, orderlies more often use ordinary belts from Soviet-era hospital gowns. He himself was tied to the bed multiple times during serious episodes of his hospitalisation.

These are typically special straps for the arms, legs, and hips, featuring soft cuffs that reduce the risk of injury to the patient.

“They tie you down, and you struggle to break free,” Andrei recalls. “It’s like a noose — it pulls you even tighter the more you resist. The belts dig into you, and you end up hurting yourself. They can tie your legs, tie your arms — crucify you, as if on a cross.”

For patients admitted in critical condition, the restraints are especially severe, Kuznetsov says:

“People lose control and insult the medical staff. The orderlies don’t seem to understand the illness; they take it personally and can hurt you. They tie your hands behind your back and loop something around your head, placing it around your neck. Suddenly, you’re suspended, your head sharply tilted back. After an hour and a half, maybe two, your body turns to stone. You can’t move, can’t turn your head or neck.”

Yevgeny Stepanchuk also speaks about restraints at the Republican Psychiatric Hospital. He was never restrained, but he witnessed it happening to other patients. For instance, one man who refused to go to sleep and remained sitting in the corridor was dragged into the ward by orderlies and tied to the bed for the entire night.

Stepanchuk says that staff at the RPH rarely attempt to engage with patients: it is simply easier for them to tie someone up than to find another way to manage the situation. At the same time, patients who resist, not understanding what is happening, risk causing themselves even greater injury. Stepanchuk suggests that this may have been the case with Ivan Khlomko.

There are no video cameras in the wards, and patients are not allowed to keep their phones, making it impossible to verify prolonged restraint independently. According to Andrei Kuznetsov, roughly one in three patients is restrained, sometimes for an entire night. He acknowledges that violent patients may need to be restrained, but emphasises that it should never be done in an inhumane manner:

“The orderlies tie you up very painfully. They do it like sadists — they don’t just restrain you; they do it to inflict maximum pain.”

Russian legislation does not specify a maximum duration for such “prolonged compression measures.” Former RPH doctor Maxim Novikov compares this to the standards in one EU country (He asked not to mention the country where he moved) where he now works. There, medical staff follow a clear protocol in acute situations: first, they attempt to talk to the patient and use behavioural techniques; if necessary, sedatives are administered. Physical restraints are a last resort and are only used after sedatives to prevent self-harm. Security staff assist, nurses check on the patient every hour, and both audio and video recordings are made. Ideally, the patient spends as little time as possible in restraints.

“Restraints are a very extreme measure, involving direct physical contact with an aggressive patient. Afterwards, medical staff must review the situation and discuss how to prevent it from happening again,” Novikov explains, reflecting on his experience in hospitals abroad.

The Chamber of Fear

In addition to restraints, the six ward has an observation room with bars that, according to Andrei Kuznetsov, resembles a prison cell. Newcomers in crisis, as well as patients who break the rules, are placed here.

Kuznetsov calls it the “chamber of fear,” a place patients dread: “If you break the rules, steal something, or hit someone, you immediately end up behind bars.” The cell is chaotic, unsanitary, and strongly smells of urine. Patients are not allowed into the corridor or to smoke. At night, they are unable to use the toilet and are left with a bucket in the cell.

“And that bucket stinks up the whole ward. In the morning, someone empties it, but during the day, not everyone is allowed out. Those who remain pee in the bucket again all day. The stench is endless,” Andrei recalls.

Yevgeny Stepanchuk also vividly remembers this cell. Several years ago, after a suicide attempt, he was brought to the emergency room in critical condition over the weekend. Instead of being placed in the usual ninth ward, he was placed in the acute care observation ward in the sixth ward.

Evgeny says he was shocked by this “cage.” Everything in the room was scattered and filthy, and the smell was unbearable. The day felt like a nightmare: “It was as if I had fallen into a horror movie about psychiatry.” One patient harassed him, while another “floated in his own space.” During the day, he was only taken to the toilet after repeated cries and requests for it. At night, the entire ward had to use the same black bucket.

What left the most profound impression on him was the staff’s treatment of patients:

“On the left, a man is wetting the bed. The orderly comes in and yells at him, ‘What, you freak, did you piss yourself or something?’ Then he grabs him and shoves his face into the mattress like a dog. Guys, you came to work — why are you behaving like scum and pigs? Why don’t you treat people like people?”

Stepanchuk immediately adds that orderlies are poorly paid, and perhaps such abuses would not occur if their salaries were higher.

A Psychiatric Diagnosis as a Stigma

According to Andrei Kuznetsov, such cruelty was possible because everyone in the hospital — orderlies, nurses, and doctors — covered for each other. When he was first hospitalised and told the staff that he planned to discuss his restraints with a lawyer, one of the orderlies warned him not to; otherwise, they would drug him heavily and keep him there for a long time. So Andrei changed his mind.

Patients rarely complain to doctors either, as the medical staff make their rounds alongside the orderlies and nurses. Andrei says patients are genuinely afraid of the orderlies. He smiles wryly, noting that in the sixth ward, there is a stand listing patients’ rights — but it seems mostly symbolic.

Yulia Fedotova, a lawyer with the Anti-Torture Team, advises that patients and their relatives always carry a voice recorder when visiting a doctor. She recommends that relatives be as loud and assertive as possible, because hospital management “will not want to deal with such people.”

Fedotova urges that any violations of patients’ rights should be reported immediately to the police and the Investigative Committee. She emphasises that achieving justice is possible, citing the example of three doctors from Interregional Tuberculosis Hospital No. 19 in Rostov-on-Don, who were found guilty of abuse of office and sentenced to actual prison terms.

The Anti-Torture Team has published detailed guidelines on how to act if you encounter violence or mistreatment in a hospital or clinic, offering step-by-step instructions for protecting patients and holding staff accountable

Former RPH doctor Maxim Novikov confirms the use of restraints, the existence of the observation ward, and the inhumane behaviour of the orderlies. He emphasises that “Matrosy” has very few qualified medical staff. In Russia, no formal medical education is required to work as an orderly, yet orderlies have more contact with patients than any other staff members. Among older Russians, a psychiatric diagnosis remains highly stigmatised, and only younger, educated people with “different values” avoid such stigma. As one might expect, most orderlies belong to the former group.

In the EU country where Novikov now works, orderlies without medical training are not allowed to treat patients. His salary is sufficient for a decent life, and staffing levels in an average psychiatric hospital are much higher than in Russia. This allows staff to devote significantly more attention to patients:

“Yes, he came to you in a state of psychosis. Yes, he is here involuntarily, but does that mean he is no longer a human being? It doesn’t work that way,” the psychiatrist explains.

Recalling his time at the RPH, Novikov adds that conditions there were terrible not only for patients but also for staff: “It’s just hell on earth. If even half of what happened were made public, people would go grey with shock.”

“Balabanov-Style at Its Worst”

Maxim Novikov, a psychiatrist who left Russia, is the only medical professional connected to Karelian psychiatry who agreed to speak with the New Tab. In the early 2010s, he completed his residency at the Republican Psychiatric Hospital, and a few years ago, he moved to Europe. Despite his experience working at “Matrosy”, Novikov becomes visibly shocked when hearing the story of Ivan Khlomko — he covers his face with his hands and says the story seems plausible:

“He wasn’t the only one in that condition. The abuse in this hospital has long been known, but this is something beyond the limit, even for the RPH. To me, this story represents a concentrated evil. Balabanov-style at its worst.”

He adds that those responsible should “their heads must roll, up to the chief doctor,” as the case clearly demonstrates gross negligence on the part of the medical staff.

Since its initial statement promising an investigation, the Ministry of Health of Karelia has yet to report any results. Neither the ministry nor the hospital under investigation responded to the New Tab’s request for comment. Although RPH Chief Doctor Irina Glatyenok generally speaks with journalists, in an interview with local media a year ago, she claimed that her facility has “no wards for violent patients and no straitjackets.”

Attempts to speak with doctors and nurses from “Matrosy” were also unsuccessful: nine people, including former staff, refused to talk to the journalist. At the New Tab’s request, Novikov contacted several of his former colleagues in Petrozavodsk to comment on Ivan Khlomko’s case, but none were willing to discuss the incident with a journalist, even anonymously.

Novikov explains that in Russia, much depends on the department head. Sometimes the attitude toward abusive conditions is “normal, we don’t do anything,” but other doctors have “zero tolerance for violence.” He knows of a case in which an orderly at RPH was fired for hitting a patient in the face.

“I don’t want to speak in slogans, but this whole story is about the ubiquity of violence and its spread,” Novikov concludes. “People are used to living with violence and bringing force everywhere. Violence is a straightforward method to make a person more manageable — especially when no one will listen to them, if they are sick.”

***

The Investigative Committee refused to initiate criminal proceedings at the request of Elena Khlomko regarding the infliction of serious harm to her son’s health. At the end of March, her appeal was forwarded to the police: the statement was accepted, but no results of the investigation have been reported. The Karelian prosecutor’s office found no “grounds for prosecutorial action,” noting that the Ministry of Health’s investigation is still ongoing.

Andrei Kuznetsov is monitoring his health, going to the gym, and taking his prescribed medication to avoid another stay at the RPH.

Evgeny Stepanchuk plans to open a private mental health clinic in Karelia, providing an alternative to Matrosy.

Meanwhile, the Republican Psychiatric Hospital is preparing to celebrate its 105th anniversary, emphasising that it is proud of its achievements and committed “to further development and improvement of medical care.”

Ivan Khlomko remains in intensive care at the Baranov Republican Hospital, in a coma, with his left leg amputated.