In Obninsk, a city in Russia’s Kaluga region, the connection with its U.S. sister city Oak Ridge is remembered only by Oak Ridge Boulevard and a local fitness center bearing the same name. Since the 1990s, the two cities have partnered in science, sports, culture, and charity, with residents exchanging visits and experiences. Against this backdrop, a children’s country music group called Vesyoliy Dilizhans (“Merry Stagecoach”) rose to unexpected success, performing across the United States and Europe. Journalist Dasha Sverchkova of The New Tab traces how the ensemble’s international journey grew out of that cross-cultural friendship — and how, in recent years, both the bond and the music have begun to fade.

The original piece was published in April 2025.

“Porushka-Paranya” with an American melody

“Oh, you, Porushka-Paranya, why do you love Ivan? Oh, I love Ivan because his curly hair is so fine,” sings sixteen-year-old Ksyusha, holding a guitar on her lap and tapping her foot cheerfully to the rhythm.

Soon, another guitar, a violin, a banjo, and a dobro join in, giving the song the rhythmic sound of American farmers’ music — country. “Chyorny Voron” (The Black Raven) undergoes the same transformation; ten-year-old Arina, who plays the dobro guitar, calls it a “psychological horror.” Seems like the girl in an oversized black T-shirt and jeans is not particularly fond of the song.

The six-string resonator guitar. Invented in the U.S. in the early 20th century, it is widely used in American country and bluegrass music.

Country music takes root in Russian folk on the third floor of the city’s Palace of Culture in Obninsk — a neat maroon-and-grey building whose entrance is guarded by the sculpture of a swan with wings outstretched. Inside, a screen on the wall alternates between the patriotic video “Everything for Victory!” and a clip featuring a participant in what the Kremlin calls its “special military operation” in Ukraine.

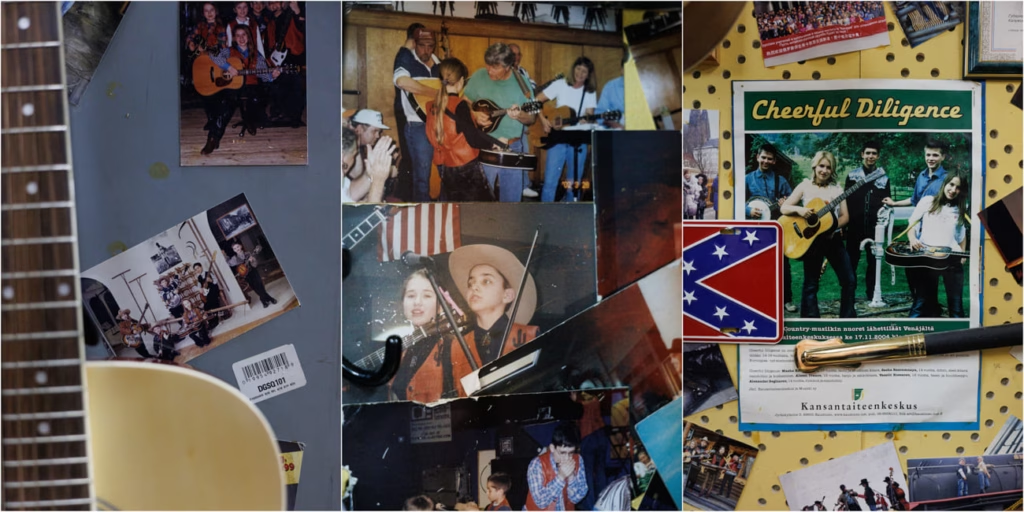

The yellow walls of a small office are densely covered with photographs, diplomas, cowboy hats and pistols from Westerns, posters of concerts abroad in Swedish, Polish, and English, and musical instruments. There are guitars, Chinese violins, mandolins, and a banjo that resembles a tambourine, featuring a fingerboard and strings. In the corner stand drums, and against the wall — a double bass.

“All of this is country,” says Aleksei Yuryevich Gvozdev, a grey-haired man in a T-shirt that reads Pink Floyd, glancing around the room. For more than forty years, he has been teaching children to play musical instruments. To give them the experience of performing, in 1988, the then 28-year-old teacher of the local music school founded a children’s country band in Obninsk, which soon took the name “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” (“Merry Stagecoach”). Its musicians grew up and moved on; today, in the Palace’s rehearsal room, its fourth lineup plays — six kids aged 10 to 19. To them, Aleksei Yuryevich is simply “Alekseich” or “Yurich”.

The ensemble’s rehearsal begins at half past seven in the evening and runs past midnight. On a small table by the entrance sit a teapot, bagels, pryaniki, and packs of rusks. “Because they spend long hours here, they need something to snack on,” Gvozdev explains.

Anya is about to turn twenty. She studies biology in Kaluga, but on weekends she comes home to Obninsk and joins rehearsals to play the violin and mandolin.

“And because I haven’t seen Kseniya in a while,” she adds with a smile, glancing at her friend.

“We come here like it’s home,” Ksusha says, brushing the rusk crumbs off her hands.

In the past — especially during summer holidays — they spent nearly every day in the third-floor room of the Palace of Culture: watching movies, racing each other to chop up salad, baking charlottes in the microwave, rehearsing.

“Nonsense, you messed it up. Do it again,” Gvozdev snaps, and Arina obediently heads out into the corridor to practice her dobro solo for “The Black Raven”. The group is preparing for summer concerts — a Christian art festival in Voskresensk and the City Day celebration in Gomel, Belarus.

“We really need to put together a Russian program. We’ve got, what, one or two Russian songs at most,” Gvozdev muses aloud.

“But for City Day, it’s the younger crowd who’ll come to listen,” Ksusha objects.

“Exactly, the young ones. They don’t want children’s songs, but nobody needs English either. They’ll say: ‘American agents!’ — and shoot us on the spot for singing in English,” Gvozdev jokes. “We need two Belarusian ones.”

Belarus is one of the few countries where “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” can still travel to perform. “There are other places too, but everything [the festivals] is restricted now. It’s not like it used to be,” the band’s leader explains. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the ensemble played at major festivals abroad, and their very first foreign concert took place in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, when that small town became Obninsk’s twin town.

Oak Ridge itself was founded in 1942 as a base for the Manhattan Project — the U.S. government’s World War II program to build nuclear weapons, directed by physicist Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves. The project produced three atomic bombs, two of which were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

People for People

Grey paving tiles, flowerbeds overgrown with weeds, broken lampposts jutting like sticks — this is what Oak Ridge Boulevard in Obninsk looks like today, a pedestrian stretch between a Khrushchev-era block and a nine-story building the colour of rusty water. Nearby stands a sports club with a faded banner: “Oak Ridge Fitness. Become the hero of your own story.” The boulevard was opened in 2002, and the fitness club in 2009. Now they are just about the only reminders of the friendship between Russia’s Obninsk and America’s Oak Ridge.

“Back in the 2000s, they tried to make it ‘pretty’ here, but vandals destroyed everything. Then the authorities just gave up,” says Obninsk journalist and local historian Aleksei Sobachkin.

Both Obninsk and Oak Ridge were born in the 1940s as sites for nuclear research. In Oak Ridge, it was the development of nuclear weapons; in Obninsk, the world’s first nuclear power plant was built. Obninsk was granted city status in 1956, while Oak Ridge received its city status in 1959.

Dr. Ken Lachman of Oak Ridge first brought together the two closed cities. Interested in how Obninsk’s Institute of Medical Radiology treated radiation sickness after the Chernobyl disaster, he came to Obninsk in the late 1980s to meet colleagues and deliver thyroid medications to Russian doctors.

In 1992, the Lachman family and Obninsk’s first mayor, Yuri Kirillov, formalised the sister-city relationship. The two cities were intended to exchange scientific research in energy and neutron physics, radiation biology, new materials, and environmental protection, as well as share experiences in business, culture, education, and sports.

Aleksei Gvozdev recalls that when he visited Oak Ridge in the 1990s, locals did not believe that the first nuclear power plant in the world had been built in Obninsk. “‘What are you telling me? The first nuclear plant was here, in Oak Ridge! We Americans built it. That’s all just propaganda over there in Russia, you didn’t build the first one!’” he mimics their voices. He admits that Cold War-era Soviet propaganda was “dense,” but in his view, not as extreme as in the United States.

The Obninsk nuclear power plant, launched in 1954, became the world’s first nuclear power station connected to a common electrical grid.

The sister cities began exchanging scientists, doctors, musicians, children’s sports teams, sending one another City Day greetings, and launching joint projects. One of them, recalls Father Aleksei Polyakov of the Church of Saints Boris and Gleb in Obninsk, was the opening of a charity dining hall. In the late 1990s, Oak Ridge residents even came to Obninsk to share experience and meet local volunteers.

“To be honest, there was a bit of window dressing, as if we were busy doing something,” Polyakov admits. “The Americans come out of the city hall; they need a ride. A staffer meets a friend and says, ‘Vanya, listen, could you give the Americans a lift?’ — ‘Sure, I’ll give them a ride.’ One of them asks: ‘Is he a volunteer?’ — ‘Oh yes, yes, volunteer!’” Polyakov laughs.

The guests were taken to meet his parishioners. After the tour, the Americans wanted to do something useful for the church, so they were offered to paint the fence. “They were given paint and brushes, and they painted a little — but mostly they took photos,” the priest recalls.

In 2010, Father Aleksei Polyakov was among those who travelled to Oak Ridge through the “Open World” program to see how charity work was organised in the United States. The priest recalls that there he saw “a different level”: volunteers peeling potatoes in a canteen, supermarkets donating food to foundations, a shelter for women facing domestic violence, and a school where teachers worked with struggling students, packing “help backpacks” with food for children from poor families.

Open World (“Otkrytyi Mir”) was a program initiated by academician Dmitry Likhachov and James Billington, the Librarian of Congress. Its goal was to allow Russian political and community leaders to visit the United States, exchange experiences, and establish professional contacts between Russian and American specialists in various fields.

“But when we asked, ‘Who exactly are the poor?’ the answer was: ‘People who make less than $21,000 a year,’” Polyakov recalls.

He believes Obninsk and Oak Ridge could never have been equal partners: their living standards were worlds apart. According to Polyakov, people in Obninsk “wanted help” from America and in the 1990s looked up to the U.S. as an “older brother”:

“As they told us, the state is by definition a poor manager. That’s why all social work comes from the bottom up — practically everyone volunteers. For us, that was unthinkable. It has to do with the mentality of the Soviet person: social work was the responsibility of the state, and no one else was allowed into it.”

Activists from Oak Ridge were ready to purchase equipment for a charity canteen and kitchen in Obninsk and to help develop a volunteer movement, but from the mid-2010s, cooperation gradually faded. As did ties between many Russian cities and their sister cities in Europe and the U.S. According to Polyakov, Obninsk’s administration had not planned to shut down the project, but the canteen never materialised. Formally, friendly relations remained: in 2016, the city authorities even invited guests from Oak Ridge to Obninsk’s anniversary celebrations.

That same year, Obninsk hosted Russia’s first public rally in support of Donald Trump, who had just won the U.S. presidential election. According to various media reports, between 10 and 20 people turned out. The police did not allow them to display pro-Trump posters, since the only permit had been granted to the event’s organiser — Obninsk blogger Artyom Mainas — who never showed up at the rally himself.

Mikhail Sinitsyn, then head of the Obninsk charity foundation “Our Children”, was also involved in building a volunteer movement. He believed it should not have been officials travelling to Oak Ridge, but ordinary citizens. On his initiative, a children’s home doctor and a social worker went to America from Obninsk. Activists from both cities cooperated for several years, but a U.S.-style volunteer model — with nonprofits founded to help those in need — never took root in Obninsk. The reason, in Sinitsyn’s view, was that Russia lacked a developed civil society. In recent years, as relations between the two countries deteriorated, Obninsk residents lost both the opportunity and the interest to build something similar.

Our Children (“Nashy Deti”) was a foundation in Obninsk that supported orphans and people in difficult life situations.

And still, some Obninsk residents attempted to maintain the friendship between the cities for a time. In 2015, for instance, Veronika Lodeikina, head of the language club “uniTED”, and translator Olga Zrodnikova organised a teleconference with Oak Ridge, where Russians and Americans discussed their daily lives in their respective towns. Zrodnikova had first visited the United States in 1999 through the “Open World’ program. As a translator, she was invited to accompany Russians from different regions into “one-story America,” where they lived in families and exchanged experiences with colleagues: “librarians with librarians, musicians with musicians, lawyers with lawyers.” Zrodnikova travelled with groups focused on nuclear nonproliferation.

The visiting Russians became minor celebrities in the U.S., being driven everywhere, filmed, interviewed on TV.”

“Americans knew very little about ordinary Russians — just as we knew little about them. Propaganda worked both ways. People literally asked us: ‘Do you have televisions at home? Do you have refrigerators? Do you even have summer?’” Zrodnikova recalls.

Olga corresponded with the family she had stayed with for fifteen years: every Christmas the elderly couple sent handwritten letters to Obninsk. “They welcomed me into their family circle. I’ve kept the whole bundle of those letters — carefully written, with little postcards,” the translator says.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the “Open World” program for Russia was suspended. Olga regrets this, because for her “it was one of the brightest chapters of my life,” and also because “the image of the enemy that propaganda creates can only be broken through personal contact.”

In 2023, the Oak Ridge city council considered ending its sister-city relationship with Obninsk because of the war in Ukraine, but American activists and scientists who had once worked with their Russian colleagues opposed the move. They argued that a sister city bond is “a relationship between people, not governments.” In the end, the council decided to preserve the partnership, but without municipal funding.

Limitless Possibilities

Aleksei Gvozdev believes that in the U.S. everything revolves around money — and he doesn’t like it.

“In Russia we have a whole bunch of scientists, but they’re not millionaires, because here we don’t do it for the money. Money exists, sure, but it doesn’t always bring happiness. When we played with “Dilizhans” on Arbat Street, our instrument cases were stuffed full of cash. People didn’t need the money, because it wasn’t worth anything,” Gvozdev recalls of the 1990s.

Back then, from the late ’80s onward, Russia entered what he calls the “American boom” — a craze for everything from the States, including music. Gvozdev was not a fan of country music himself, but on that wave he remembered a banjo he’d once received from a friend in exchange for a guitar. Through microfilms at the library he figured out the intricacies of playing it, and among his students he found a boy who wanted to become a banjo player — Ilya Toshinsky, the group’s first member. “We took his classmate on bass, found a girl singer, added a violinist and a double bassist,” says Gvozdev. This was the birth of “Vesyoliy Dilizhans”, which played bluegrass — a branch of country music.

Microfilm is a type of light-sensitive photographic film that stores documents in a roll format, with frames arranged in one or two rows. It can also refer to a photocopy of documents, manuscripts, and books that are reduced significantly in size and captured on photographic or motion picture film.

Some sources note that this was actually the band’s second lineup. But according to Gvozdev, the earlier musicians he worked with had never called themselves “Vesyoliy Dilizhans”. For him, Toshinsky’s group was the real first lineup. In the VK page of the later “Novy Dilizhans” (“New Stagecoach”, that lineup is also called the first.

The American music genre of country. In bluegrass, each musical instrument takes turns being the lead, while the others fade into the background.

“Everyone was thrilled by American music, by its quality, by its virtuosity. We didn’t expect to get famous — we were just kids, simply playing. But we did dream [of making it],” Toshinsky remembers.

In the early 1990s, “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” made its first trip to the U.S. — to Oak Ridge, through the sister-city exchange. “It felt a little scary,” Gvozdev says. “There had been the Cold War, after all, and America was the main enemy. We worried about what would happen — and so did the Americans.”

Although the Oak Ridge audience seemed wary at first, the anxiety proved unfounded: the Obninsk musicians were warmly applauded. For two weeks, according to Gvozdev, “Dilizhans” “worked off the sister-city program,” giving concerts at different companies. After that the group wanted to stay a few days longer to attend a major country festival. “We’d come from free Russia. There was freedom, right down to choosing our director, mayor, governor. That was the time,” he recalls. But the Oak Ridge city council — “a bunch of dyed-in-the-wool old men,” as Gvozdev calls them — refused to let the Russians stay. Escorted by three police cars, the musicians were taken to the airport.

Back in Obninsk they were met with a newspaper article headlined “Defectors”: local journalists thought the musicians had wanted to remain in America. From then on, “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” gained popularity both in their hometown and across Russia. They never again tied themselves to the sister-city program, though the Obninsk mayor’s office continued to cite their success as its own achievement.

The band was invited onto television; they were featured in the program “Under 16 and Over”; they worked with composer Grigory Gladkov. They played on the Arbat and at La Cantina, a Mexican restaurant in Moscow where foreigners gathered. It was there that an American producer noticed them, and soon these small-town Russians were making regular trips to the United States. American audiences looked at the Russian teenagers “playing country better than the Americans” as something exotic.

“It was a wave — from perestroika through the end of the ’90s — when we and the U.S. were really close friends, or at least it seemed so,” says bassist Sergei Olkhovsky.

The group toured across Tennessee. “Everywhere we went, TV, newspapers wrote about the Russian band,” Gvozdev recalls. He remembers how NBC journalists came to Obninsk to shoot a film about “the backwoods, where a boy plays some shabby old banjo.”

The ensemble spent whole summers in the U.S. Gvozdev himself grew tired of the long trips, which consumed so much time, and the group began performing in Europe. Their bright, talented music drew invitations to festivals in Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Italy, France, and other countries.

In 1994, the Russian authorities came up with the idea of gathering talented children from the former Soviet Union and sending them on the icebreaker Yamal to the North Pole, where they would give a concert on the ice, broadcast live. “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” was invited. “The trip cost $20,000 per person. They fed us nothing but lobster and the fanciest delicacies,” Gvozdev recalls.

By the late 1990s, seven members of “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” first lineup had signed a contract with Sony Music and stayed in the U.S. Their leader returned to Russia: he wanted to live in Obninsk.

“In Russia everything was falling apart, the kids were 18–19, and life here was uncertain. Staying there — that was prestige,” Gvozdev says thoughtfully. “I can’t say it worked out for everyone: some are repairing cars, some are farming. Only Toshinsky — he’s the real star musician.”

Between Russia and the U.S.

The musicians who stayed in America now live in Nashville, Tennessee’s capital. All of them are still involved with music — some professionally, like guitarists Ilya Toshinsky and Aleksandr Ostrovsky, others more as a personal passion.

Bassist Sergei Olkhovsky once ran a car business, but it didn’t suit him, and today he works as a mechanic. He has a wife, grown children, a grandson, and a house with peonies in the garden. Olkhovsky has not been back to Obninsk “in ages,” but his parents often visit Nashville — “they like spending the winter here.” Sergei still plays bass: in drummer Aleksandr Arzamastsev’s small studio, he records “ideas that might someday turn into something.”

Sergei says he is happy and does not regret the path his life has taken — though perhaps he would not mind retiring in Russia one day.

Aleksandr Ostrovsky has spent the last fifteen years playing guitar for American musician Darius Rucker, touring frequently — something he is delighted about. “As a kid I watched Queen concerts and wanted to play stadium solos like Brian May. I didn’t quite become Brian May, but my dream came true,” Aleksandr laughs.

American musician, frontman of the band Hootie & the Blowfish. One of the few African Americans to achieve success in country music. Winner of three Grammy Awards.

At first, the original lineup of “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” had no plans to remain in America. They wanted to perform abroad but live in Russia. Yet frequent trips to Nashville to record and play shows gradually drew them into U.S. life. When Gvozdev left the band, he took the instruments back to Russia with him, and the musicians had to start over. The vocalist, drummer, banjoist, two guitarists, a violinist, and a keyboard player formed the country group “Bering Strait”. “It connects Russia and America,” Toshinsky explained of the name.

The group became popular in the United States, touring the country from Miami to Boston. In 2003, they were nominated for a Grammy for Best Country Instrumental Performance. Sergei Olkhovsky heard the news while home in Obninsk for New Year’s. “In the morning my dad came into work, and his colleagues told him, ‘You’d better buy us all a drink — your son’s on TV,’” the guitarist recalls.

They didn’t win the Grammy, but they made history as the first — and so far only — Russian band to be nominated. More concerts followed, along with radio and television appearances, and one of their albums even broke into Amazon’s list of bestsellers. But gradually, record labels’ interest in “Bering Strait” faded.

According to Ostrovsky, the original “Dilizhans” ensemble had been “assembled” when they were children, but as they grew up and developed their own interests, the glue holding the band together dissolved.

“That’s it. We had a good run,” says Olkhovsky of “Bering Strait’s” end.

In 2025, Ilya Toshinsky received another Grammy nomination. For several years in a row he has also won MusicRow Awards in the U.S. as Best Guitarist. As a session musician, he creates guitar parts for major country artists — Dolly Parton, Taylor Swift, and many others.

Once a year, Ilya returns to Obninsk to spend time with his parents. He says he feels lucky to have been born there and hopes someday to bring the experience he has gained in America back to Russia.

Why the Second “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” Stayed in Russia

When Gvozdev returned to Russia, in 1998 he assembled a new “Vesyoliy Dilizhans”. This group also traveled to the U.S. and Europe, but this time their leader was more cautious: he never signed contracts with American producers again.

The young musicians were inspired by the first lineup’s example, but they didn’t want to emigrate, fearing they would end up unwanted there, says guitarist Aleksei Ivanov from Obninsk, a member of the second “Dilizhans”:

“To be honest, we were afraid. We wanted to travel, to perform in America, but we wanted to stay and develop in Russia.”

The second lineup formed its own group — My Sister’s Band — and shifted from country into the more popular pop-rock genre, recording albums and writing soundtracks for films. But their musical career never took off. Ivanov became head of marketing at a manufacturing company; bassist Vasily Kosarev moved to Georgia, works as a sales manager for a major U.S. corporation, and plays in a local cover band; drummer Aleksandr Degtyaryov now manages a department in a construction firm; vocalist Maria Razumnaya has a family; guitarist Aleksandra Razumnaya, runs her own business and, together with Ivanov, writes songs and streams on YouTube and Twitch.

“English Songs Are Out, We’re Dropping Them”

These days, when “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” performs in English, audiences often say: “Sing in Russian, enough of that American language.” So, according to Aleksei Gvozdev, the band has started adapting Russian songs into a country style.

“When the special military operation began, Yurich really wanted to change the repertoire. Because we couldn’t agree on the program, our career stalled. But I trust him — maybe somewhere we really did get scolded. It just happened too fast for us: we came to rehearsal, and suddenly — ‘English songs are out, we’re dropping them.’ Now everything’s fine, Yurich lets us sing in English at country events,” explains Ksusha during one of the group’s rehearsals.

Gvozdev doubts that relations between Russia and the United States will ever return to what they were, since America “only pursues its own interests.” First, he says, Americans were afraid of Russians (“the Cold War — they thought we’d bombard them with nuclear missiles”), then they realized Russians weren’t dangerous (“they seemed normal”), but since the 2000s they’ve treated Russians as nobodies. “I think: well, bastards, you need to be put in your place. Putin, thank God, he figured it out in time — he’s competent after all,” Gvozdev says.

Today the ensemble’s artistic life rarely extends beyond Obninsk. Russia’s country-music community is small — mostly people over 50 — and there are hardly any events left where such music can be performed. The International Festival of Bluegrass in Vologda, launched in 2010 and once a stage for both “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” and “Bering Strait”, has not been held since 2018.

This year the band was invited to a festival in the Netherlands, but they won’t go: the trip has become too expensive.

“We calculated it — there’s just no sense in flying somewhere through Turkey with instruments,” Gvozdev explains.

For him, the hardest part is what this means for the younger musicians. To grow, he says, children need motivation — “the idea that you can go here, go there” — and exchanges with international performers, since musicians always learn from one another.

“But Yurich invests in us. Here we play on the very best. Dasha, how much does your guitar cost?” Ksusha asks.

“One and a half million,” replies the guitarist.

“Mine’s about 700,000. All of it’s Yurich’s money. They lived in the States, traveled, bought things. My guitar, for instance, was played by Natasha Borzilova, who won a Grammy. A cultural center here would never buy that, or they’d buy something fake,” says Ksusha.

Natasha Borzilova — lead singer of the first lineup of “Vesyoliy Dilizhans” and later of the American band “Bering Strait”, nominated for a Grammy in 2003. She lives in Nashville.

Anya shows her violin: “He gave me this as a birthday present when I turned 18.”

For Aleksei Gvozdev, the ensemble is like a family — he has no wife or children — and he has no desire to abandon American country music, even if it is no longer loved in Russia. He has poured his entire life into this unique band. Memories of the group’s international success clearly bring him joy. Smiling, he points to the rehearsal room wall, covered with posters from festivals abroad: “That’s a Finnish poster, those are Swedish ones. Look, generations are growing.” He hopes that someday another window onto the wider world will open for his students:

“If things improve, we’ll go again. Because we’re the only ones here.”